18 August 2019 Edition

A turning point in our lives

The point of no return – August • 1969 • Lúnasa – Ni raibh aon dul siar as ansin

Why is it that the older we get the drier and hotter were the summers of our youth as they replay in our memories. The summer of 1969 is like that. I was 16. Along with my brother Seany, who was 15, and a bunch of our friends, our social life centred around St Teresa’s Youth club on the Glen Road in Andersonstown.

We hung out there almost every night. Our interest was in girls and music, and girls, and occasionally table tennis, and girls. The music was great. We held a disco every Thursday evening. Tamla Motown was big. I still love ‘My Cherie Amour’ by Stevie Wonder. The Stones ‘Honky Tonk Women’, Presley’s ‘In the Ghetto’, ‘Break Away’ by the Beach Boys, and John Lennon’s anti-Vietnam War song ‘Give Peace a Chance’ and many more were all part of the acoustic for that summer.

In July, eight of us crowded into the Lavery family home in Corby Way to sit up all night and watch the Moon landing. The pictures of Armstrong stepping onto the moon were awful but we were all caught up in the exhilaration of his “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”.

Three weeks later and reality came crashing into our lives. On the Thursday night, August 14th, our disco was crammed with bodies dancing to the latest hits. Someone banged on one of the doors of the Parochial Hall. One of my friends went to ask what the problem was. When he returned he told us that there were men and women at the door looking the keys to the school. They said they had been forced to leave their homes down the road and needed somewhere to go for the night. My friend sent them to Fr Mc (McNamara) the local Parish priest. We went back to enjoying our disco.

The next day was the Feast of the Assumption – a holy day of obligation. We met up to go to mass. When we arrived at the Glen Road we saw cars, vans and some lorries outside the main doors of the Primary School. We walked over to see what was happening. The school was now occupied by men, women and children – families – who during the night had fled their homes in the Clonard and lower Falls area. Their streets had been attacked by loyalist mobs, supported by the B Specials (an almost exclusively unionist auxiliary police force) and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), backed by Shorland Armoured cars.

Classrooms which we had occupied as children only a few years earlier were now home to terrified families, some with all of their meagre possessions in a few bags, others with bits of furniture that a van or lorry had managed to take away. The shock and terror on their faces was plain.

I vaguely remembered that there had been tension over the summer months, and we had heard of trouble in Derry in recent days (the Battle of the Bogside). But for the most part none of us were that interested in the news.

We now learned that as we had enjoyed our disco the previous night hundreds of families in the lower Falls and Clonard, and in north Belfast, had been forced to leave their homes. Loyalist mobs had attacked Catholic families in Percy Street and Conway/Cupar Streets and the small network of streets between the Falls and the Shankill. Scores of houses and shops had been destroyed.

The RUC and B Specials had also opened fire. RUC Shorland Armoured cars fired indiscriminately into Divis Flats. Nine-year-old Patrick Rooney was killed in his bed. A British soldier Hugh McCabe, home on leave, was also shot and killed. Much of Conway Street was destroyed. Terrified families had fled carrying whatever they could on their backs wrapped in blankets or plastic bags.

Many refugees made their way to St Teresa’s Primary School. Others went to Holy Child Primary School and La Salle Secondary School, both close by in Andersonstown. Hundreds more travelled to the 26 counties.

Those organising aid for the increasing numbers of refugees in St Teresa’s needed cars and volunteers to go down to the Clonard and lower Falls to help evacuate streets. It was believed more attacks would occur. I couldn’t drive but I had willing hands. I joined up with Joe Savage who had a mini and we went to Waterville Street at the back of Clonard Monastery to take away belongings and children and elderly folks. An hour or so later, a few yards just around the corner in Bombay Street Fian 15-year-old Gerard McAuley was shot and killed by loyalists. Bombay Street was totally destroyed in a firestorm of petrol bombs.

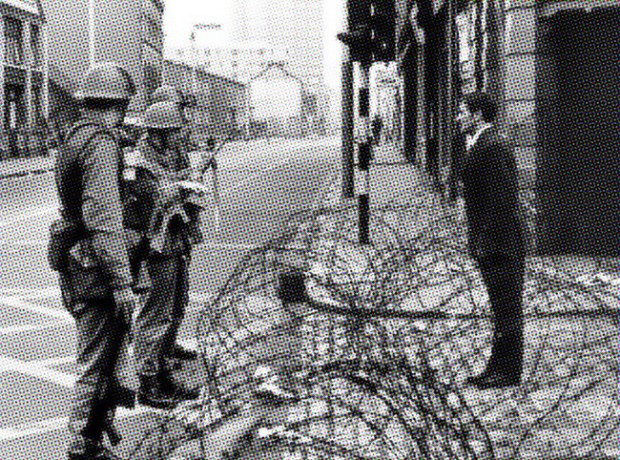

In the days that followed, Joe and I travelled down into the Falls. We transferred food and clothing, and occasionally people, between the refugee centres. On these journeys I saw the extent of the destruction along the Falls Road. Burned out terraces of small houses, gutted shops, old Mills that had stood for a hundred years reduced to empty shells and terrified families living in schools. I also saw my first British soldiers.

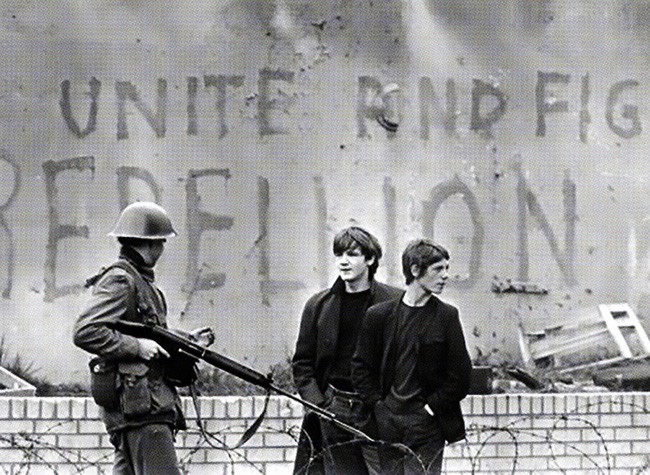

It was an awful time. For those who were homeless, the families who were bereaved and the communities then living under siege. But it was a time of enormous generosity and courage by those who provided food and shelter, who took destitute families into their homes, and who provided a measure of safety behind the barricades that now stretched the length of the Falls and cut across what had been mixed streets between the Shankill and the Falls.

Unionist leaders blamed republicans for what had occurred. Unionist government ministers went so far as to accuse nationalist families of burning down their own homes. In the period between August 14th and August 18th eight people were shot dead and almost 2000 families turned into refugees.

Fifty years ago, August 1969 was for me and for many others a turning point in our lives. It was the first time I even thought about partition. The sectarian intransigence of the Unionist regime at Stormont, and the subsequent willingness of British governments to defend the status quo, made me think seriously about the nature of the northern state.

It still took a while for me to realise that the politics I was beginning to now grapple with in discussions and arguments with friends and family were republican. But I got there in the end.

• Richard McAuley is a republican activist and former political prisoner.