18 August 2019 Edition

Any language is an arena of struggle

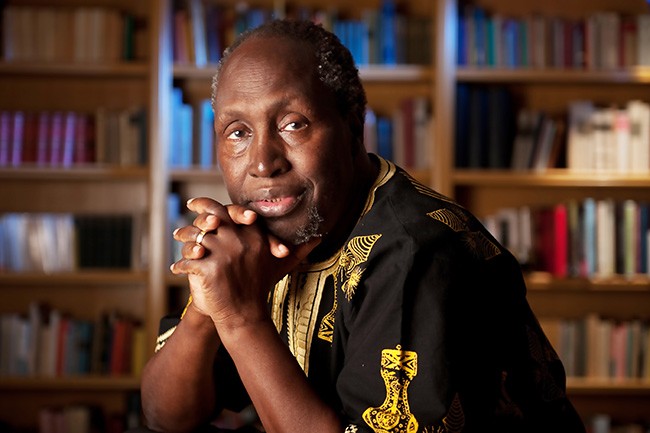

• Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Late last year Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o spoke at the LÍON, Limerick and Languages: Revival, resurgence and new beginnings conference in Mary Immaculate College, an event organized as part of Bliain na Gaeilge. Luke Callinan of An Phoblacht spoke to Ngũgĩ about the importance of language and culture in the context of a struggle for national liberation and self-determination.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, USA. Originally from Kenya, Ngũgĩ has been a recipient of numerous literary prizes, and his name has been mentioned as a leading contender for the Nobel Literature Prize.

Throughout Ngũgĩ’s youth and adolescence Kenya was a British settler colony and this lived experience of a colonial regime and of the 1952-’62 Mau Mau Uprising, had a profound impact on him, becoming a central theme in much of his writings. He was committed to communicating with ordinary Kenyans in the languages of their daily lives and unequivocally championed their cause in his literary works, which were sharply critical of the inequalities and injustices in Kenyan society.

In 1977 a play Ngũgĩ wrote entitled Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), was performed in an open air theatre with actors from the workers and peasants of the village. He was subsequently imprisoned without trial at the end of 1977 and while in prison he wrote the novel Caitani Mutharabaini (1981), translated into English as Devil on the Cross (1982), on prison toilet paper.

It was at this point that Ngũgĩ made the decision to abandon English as his primary language of creative writing and instead committed himself to writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue.

An Phoblacht: How important is linguistic independence to a national liberation struggle?

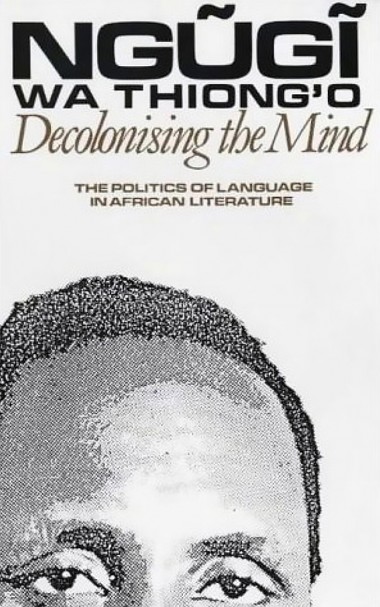

Ngũgĩ: I have tried to explore this question in my books, particularly Decolonizing the Mind; and Something Torn and New. I have described language as the memory bank of a people’s experiences of history of which they are also makers. I have also described language as the natural computer, a natural hard drive.

When you lose that hard drive you lose all the memories and knowledge and information and thoughts carried by that language, in this the language of one’s birth, one’s culture, one’s people. That’s why systems of conquest, colonisation and domination, go for the linguistic jugular.

So national liberation must, of necessity, involve at the very least a recovery of a people’s linguistic base. My position is simple: If you know all the languages of the world and you don’t know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue and add all the other languages to it, that is empowerment.

An Phoblacht: On the question of Africa and cultural colonisation you have said that “the most important area of domination was the mental universe of the colonised, the control, through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relationship to the world”. How do you define cultural colonisation and how can a post-colonial nation reverse the effects of such a traumatic collective experience?

Ngũgĩ: The economic and political control of a people can never be complete without cultural control. In some of my books, I have compared culture to a flower. Culture is to a people what a flower is to a plant. The flower is beautiful, beautiful colours, which also express the identity of the plant. But what is important about a flower is not just the colour but also the fact that it carries the seeds of the tomorrow of that plant. Our languages carry not only memories but also the seeds of our future.

An Phoblacht: You described in your book Decolonising the Mind “Afro-European literature” as “literature written by Africans in European languages in the era of imperialism”. How important is pre-colonial native language literature in this context?

Ngũgĩ: I would now call it, Europhonic African Literature, part of the global Phonic literature. This is the literature written by intellectuals of one language, culture and history but in the language of another culture and history. I would place literature written by Irish intellectuals in English, in that category, of phonic literature. This is not to diminish the quality and genius of that literature, but it is to distinguish it from literature written by Africans in African languages. We should not let Phonic literature usurp the identity of African languages, a phenomenon I describe as Literary Identity Theft (LID).

An Phoblacht: You link the creation of national native African literatures with the anti-imperialist struggle – “writing in our languages per se ... will not itself bring about the renaissance in African cultures if that literature does not carry the content of our people’s anti-imperialist struggles to liberate their productive forces from foreign control”. Is an author’s conscious acceptance of this responsibility essential in the creation of a truly post-colonial national literature?

Ngugi: No, but a language, any language, is an arena of struggle. So within any language, there will then be struggle of ideas and visions.

An Phoblacht: In this era of social media, live-streaming and increasing online media platforms, what role do you see for theatre, and other forms of literature, as an expression of working-class experience?

Ngũgĩ: Theatre should still play a big role in the self-consciousness of a people. But theatre will also utilise any new technologies, including social media and live streaming.

An Phoblacht: While a national language in post-colonial nations is often seen as an important symbol of independence, policies that facilitate its revival are often met with apathy, confusion and opposition. Why do you think that this is the case and how can it be challenged?

Ngũgĩ: The colony of the mind is always harder to fight. But we should never give up the fight. And we should not be isolationists. As I said above, with the language of one’s culture as the base, one can and should add more languages to it. Monolingualism is the carbon monoxide of cultures. But Multilingualism is the oxygen of cultures. Our languages should be part of that oxygen.

An Phoblacht: Why in your view are neoliberal post-colonial states so reluctant to deal with issues of economic inequality arising from a legacy of impoverished native-speaking rural communities? Can this be successfully redressed?

Ngũgĩ: We have accepted relationships of hierarchy as normal. My language is higher than your language; my culture higher than yours. We have accepted the colonial and imperial fallacy that for one language to be, others must cease to be. We see the same thinking and practice in the area of economy and politics. For a billionaire to be, there must be a billion poor. We have to continually reject a world of palaces for a few built on prisons for the many; splendor for a few built on the squalor of the many. A network of equal give and take must replace that of hierarchy. The struggle continues.

Read more about the life and works of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o at: ngugiwathiongo.com.