29 August 2019

Daniel O’Connell was not a ‘liberator’ of the people

“The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the Empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons…” – Daniel O’Connell

The RTÉ two-part documentary on Daniel O’Connell presented by Olivia O’Leary has renewed debate on the legacy of this towering political figure who dominated the first half of the 19th century in Ireland. O’Leary’s presented the still prevailing establishment view of O’Connell as the great ‘constitutional nationalist’ promoting peace, in contrast to the ‘violent’ Republicans. And again alternative more informed views of O’Connell were ignored.

O’Leary presents O’Connell as a great humanitarian and man of peace who opposed the use of physical force in any form to achieve political objectives. In her first programme – I have not yet seen the second – she emphasises this repeatedly but pays little attention to what O’Connell’s real political objectives were and she fails to ask who in Ireland he truly represented. An honest answer to that question is that O’Connell represented the interests of wealthy Catholics and his whole career was based on advancing them, removing the last obstacles to their joining the ranks of the privileged along with privileged wealthy Protestants, and all under the British crown.

Of course this truth is obscured by the other side of O’Connell – his incredible popularity and populism which saw him mobilise millions of impoverished Irish people in his campaigns for so-called Catholic Emancipation and for the Repeal of the Union. His oratory and wit were legendary; like all populists he could read the public mood and change his principles and his oratory accordingly, while keeping in sight his own interests and that of the class he represented. Such was his power, however, that he retained a hold on the popular imagination long after his death. He was seen as a powerful figure who challenged the British government in Ireland. This was his image in folklore and balladry, in much the same way that Napoleon Bonaparte was celebrated in Ireland because he nearly toppled British power, even though he was himself a tyrant.

But a look behind the myth at the reality of O’Connell reveals a very different picture. As a trainee barrister in Dublin he joined the Lawyers Artillery Corps, the British militia that hunted down the United Irishmen in 1798 and Robert Emmet and his followers in 1803. During Emmet’s rebellion O’Connell was actually on duty and took part in searches. He abhorred the Republicanism of the French Revolution and of the United Irishmen. To guests in his lavish house in Merrion Square in 1842 he opined that Emmet “deserved to be hanged”.

In 1821 when King George IV of England visited Ireland O’Connell was prominent among the Catholic loyalists paying homage to him, presenting him with a laurel crown and even pledging to raise money for the building of a royal palace!

‘But what of Catholic Emancipation?’ you may ask. What indeed. Four years after ‘Catholic Emancipation’ O’Connell himself admitted in an 1833 Address to the Irish people that it was “principally useful to persons in rich or at least comfortable circumstances in life”. Far from addressing the gross injustices, legal, political, social and economic, being suffered by the mass of the Irish people, ‘Emancipation’ simply opened more doors for wealthy Catholics, while leaving untouched the real conquest of Ireland by England on which the old Penal Laws were based.

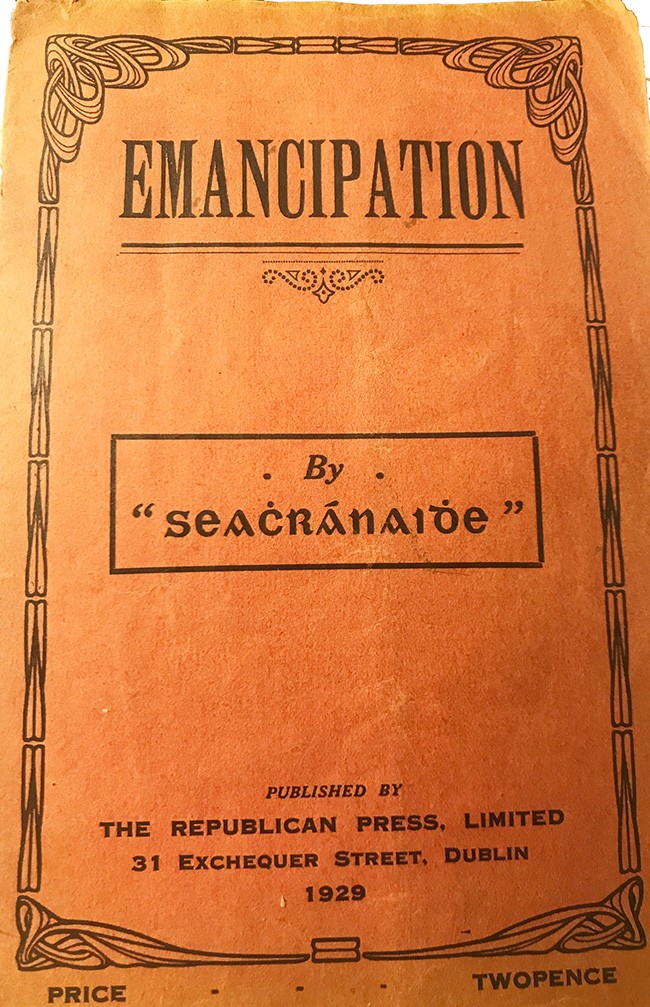

During the Centenary of Catholic Emancipation in 1929 a pamphlet simply called ‘Emancipation’ by ‘Seachránaí’ was published by the Republican Press. The author behind the pen name was Frank Ryan, editor of An Phoblacht. In his pamphlet Ryan argued that the Penal Laws were not designed to stamp out the Catholic religion or advance Protestantism but to consolidate British rule and landlordism in Ireland:

“The aim of the conquerors (frankly admitted by themselves), was to render the Irish people impotent in Ireland, by subjugating nine-tenths of native stock to the rule of one-tenth who were Planters. It so happened that Ireland was a Catholic country and that the conquerors were Protestants. The difference in religion was but an incident. Had Ireland been a Protestant country, Penal Laws would have been enforced. Or had the Conquerors been Catholics, there would still have been Penal Laws. For the Penal Laws were not framed for the advancement of one religion, nor for the suppression of another; they were not anti-religious but anti-Irish.”

By 1829 it was long past time when the British government could safely repeal remaining Penal Laws and grant ‘Catholic Emancipation’ without in any way threatening the Union or the landlords. In fact the ‘Emancipation’ legislation while opening new career paths to wealthy Catholics, actually disenfranchised the forty-shilling freeholders, taking the vote from the very tenant farmers who had backed O’Connell’s campaign. This, said Ryan, “placed our destinies in the hands of the landlords”.

• Frank Ryan's pamphlet denied that O'Connell was a 'Liberator'

Frank Ryan’s condemnation of O’Connell echoed that of James Connolly who in his ‘Labour in Irish History’ (1910) describes the years of O’Connellism as ‘a chapter of horrors’. He highlighted O’Connell’s vehement opposition to trade unions. After initially courting their support for his campaigns he quickly turned against them once he had secured the support of the privileged in Ireland and as he tried to build an alliance with the Whig Party in the British Parliament. In that Parliament he denounced trade unionism in Dublin and, tied as he was to the Whig government, he also refused to support the demands of the Chartist movement for voting rights and other basic reforms.

There was widespread disillusionment in Ireland at the lack of change resulting from ‘Emancipation’. O’Connell was forced to recognise this, as quoted above in his Address of 1833. In that same document he made the extraordinary statement that “the only thing to impede the prosperity and freedom of Ireland, is the folly and crimes of the people”. This was a reference to the widespread attacks on landlords and their property by Whiteboys and Ribbonmen who were protesting against landlord tyranny and the tithes (taxes) that the people were forced to pay for the upkeep of Anglican clergy. In the same period, as he described the Irish people as their own worst enemy, O’Connell courted the Whig government. He agreed to stop working for Repeal of the Union, in return for other concessions, and said:

“The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the Empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons if made so in benefits and in justice; but if not we are Irishmen again.”

Despite the fact that he was himself an Irish speaker and that Irish was then the majority language in Ireland, O’Connell discouraged the use of the language and said that “the superior utility of the English tongue as the medium of all modern communication is so great that I can witness without a sight the gradual disuse of Irish…”

Credit is due to O’Connell for one principle that he upheld and that was his opposition to slavery. He was consistent in this and was a friend of the African-American leader, and former slave, Frederick Douglass.

However, when it came to the political enslavement of his own country and the plight of the impoverished masses who were his followers, O’Connell was highly skilful at using them but in the end he abandoned them. His Repeal campaign in the early 1840s mobilised millions of people at monster meetings throughout the country and in his oratory he liked to hint at possible rebellion if the Union was not ended.

But all knew he opposed physical force and he had done everything to prevent the people having the ability to defend themselves. He had created among the masses a total political dependence on himself and on the wealthy Catholic laymen and clergymen who marshalled his movement. The British government had the measure of him and called his bluff in 1843 when they banned his proposed monster meeting at Clontarf. O’Connell backed down and ordered the people to go home. That was effectively the end of his political career.

O’Connell pioneered mass mobilisation but for the narrowest political objectives. Writing at the time, the socialist Frederick Engels said O’Connell did not really mean to achieve Repeal “since he uses the impoverished, oppressed Irish people to embarrass the Tory ministers and to help his middle class friends to get back into office”.

By the time of O’Connell’s death in 1847 Ireland was in the grip of the Great Hunger and as a direct result of the type of paternalistic leadership given by him and his lieutenants, and their determination to ensure that the people were unarmed and obedient to authority, the British government was able to export food from a starving country and to use the catastrophe to eliminate from the island millions of people by hunger, disease, eviction and emigration.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures