4 July 2019

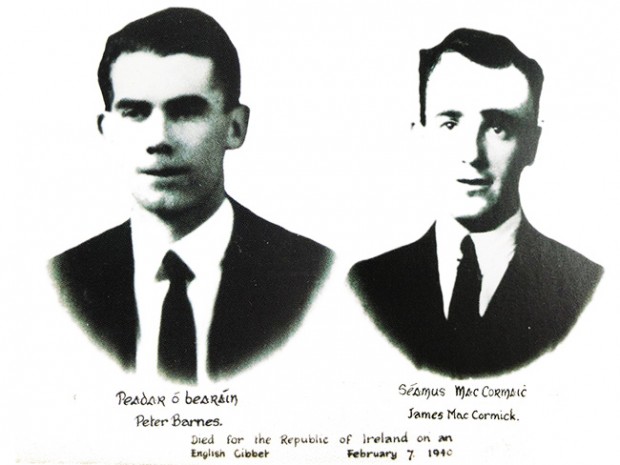

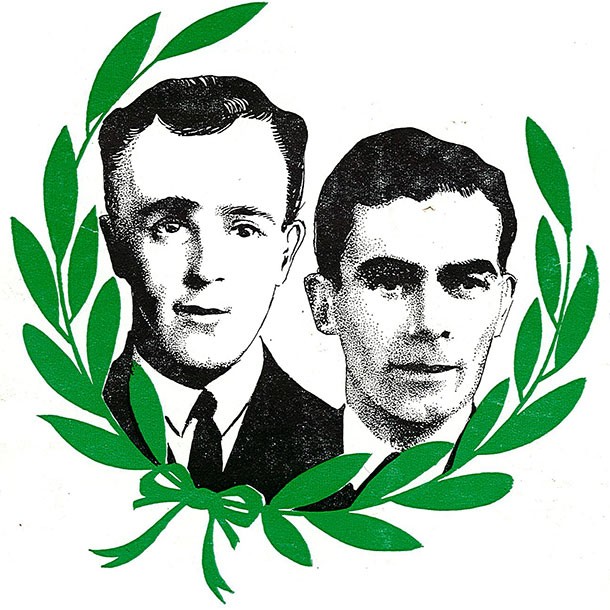

The re-interment of Peter Barnes and James McCormick

Remembering the Past 50th Anniversary

“The noble idealism of Pearse, the social and economic philosophy and aims of Connolly, and the fighting and courageous heart of Cathal Brugha.” – Jimmy Steele

IRISH republicans Peter Barnes and James McCormick were hanged in Winson Green Prison in Birmingham on 7 February 1940. They were buried in the prison ground and plain crosses with only their initials marked the graves. It took nearly 30 years before relatives were allowed to reclaim their bodies.

Peter Barnes was born in Banagher, County Offaly, in

1907. At the age of 14 he joined Fianna Éireann and, three years

later, the IRA. He was one of the first to volunteer for active

service in England during the campaign of 1939 and was appointed

Transport Officer, operating between Glasgow, Liverpool and

London.

James McCormick was born in Mullingar, County Westmeath,

in 1910. He joined the IRA in Tullamore. In early 1939, he

volunteered for active service in England. He served for some time as

Operations Officer in London and Birmingham before being posted to

Coventry in May 1939. By August 1939, he was appointed O/C of

Coventry.

On 25 August 1939, a bomb exploded outside a shop at the

Broadgate Centre in Coventry, killing five people. The bomb was

concealed in the carrier of a bicycle and prematurely exploded. It is

believed it was intended for an electricity generating station

outside the town. Neither Barnes nor McCormick was responsible for

placing the bomb.

Within hours of the explosion, Peter Barnes,

who was in London on the day of the explosion, was arrested at 176

Westbourne Terrace, where he was lodging. Three days later, McCormick

(alias James Richards) was detained along with the other tenants of

25 Clara Street.

TRIAL

The

trial commenced in December 1939. Peter Barnes and James McCormick

were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. Throughout the

court case, McCormick remained silent until he told the court: “As

a soldier of the Irish Republican Army, I am not afraid to die, for I

am dying in a just cause.”

Barnes addressed the court,

stating:

“I would like to say as I am going before my God, as I

am condemned to death, I am innocent, and later I am sure it will all

come out that I had neither hand, act or part in it. That is all I

have to say.”

On the night before his execution, Peter Barnes

wrote to his brother, protesting his innocence:

“If some news

does not come in the next few hours all is over. The priest is not

long gone out, so I am reconciled to what God knows best. There will

be a Mass said for us in the morning before we go to our death. Thank

God I have nothing to be afraid of. I am an innocent man and, as I

have said before, it will be known yet that I am.”

On the same

night, James McCormick wrote a letter to his sister, both his parents

being deceased:

“This is my farewell letter, as I have been just

told I have to die in the morning. As I know I am dying for a just

cause, I shall walk out tomorrow smiling, as I shall be thinking of

God and of the good men who went before me for the same cause.”

In

Winson Green Prison, at 8:50am on 7 February 1940, Barnes and

McCormick received a final blessing. Minutes later they walked

together to the scaffold and were hanged by four executioners.

Widespread protests by Irish people at home and abroad and pleas for

clemency were ignored by the British Government. Public mourning was

widely observed in Ireland on the day of the

executions.

MULLINGAR

As

early as 1949, a committee was formed in London to press for the

return of the bodies. This was finally fulfilled in 1969. The bodies

were removed from the prison yard and flown to Dublin. On arrival at

Dublin Airport they were met by family members and an IRA guard of

honour.

The re-interment in Mullingar was attended by an

estimated 15,000 people. Mass was said in Irish in the Cathedral

before the funeral to Ballyglass Cemetery. Among those attending were

three brothers of Peter Barnes and a sister and brother of McCormick.

The funeral was also notable for the graveside oration by veteran

Belfast republican Jimmy Steele. He denounced the political direction

of the IRA leadership in remarks that were a prelude to the split in

the IRA and Sinn Féin later that year. That speech has often been

referred to in passing in histories of the Republican Movement but

until recently a transcript or even substantial quotations were not

available because what became the leadership of the ‘Official’

Republican Movement controlled the ‘United Irishman’ newspaper

which did not report the speech. ‘An Phoblacht’, the

‘Provisional’ Movement paper, was not founded until 1970, so here

we carry extracts from Steele’s speech for the first time. It is

notable that the speech does not conform to the false stereotype

propagated by some that the Provisionals were right-wing and

anti-socialist.

Jimmy Steele Oration

Referring to those claiming to be socialists who claimed Partition was unimportant, Steele said:

“Of course the British socialists adopted the very same attitude to James Connolly, before 1916, when they told him that Irish freedom was not a cause with which he, as a worker, should concern himself. To which Connolly replied that Irish independence must be won before Irish workers could be masters in their own land. And that without political independence, the way to social and economic progress would never be clear. And away back in 1914 when Redmond and Devlin had agreed to partition, Connolly wrote that to it, Labour should give the bitterest opposition. Against it, Labour and Ulster should fight, even to the death if necessary, as our fathers fought before us. And just a few hours before his death he said to his daughter, Nora, ‘The socialists will never understand why I am here. They all forget that I am an Irishman.’ Others too, wearing the tag republican by advocating attendance at Stormont and Leinster House have come to accept the two-state situation, thus helping to perpetuate partition.

“Barnes and McCormick did not accept this position. They acted as Connolly would have acted and fought to the death against it. That was why they died. There are those who would decry their sacrifice and speak of the futility of martyrdom and cynically refer to glorious sacrifices. I will let Connolly answer those people as he answered the judges at his own court martial, ‘Believing that the British government has no right in Ireland, never had any right in Ireland and never can have any right in Ireland, the presence in every one generation of Irishmen of even a respectable minority read to die to affirm that truth, makes that government forever a usurpation and a crime against human progress.’

“Yes, my friends, just as Emmet and the Manchester Martyrs and Kevin Barry died, so did Barnes and McCormick, in the same cause, in the same way and by the order of the same hangman, the hangman of the western world, England.

“I’m sorry to say there has been a strange, if not deliberate silence, among republicans about that period when Barnes and McCormick were active. A period known as the Forties. Let there be no glossing over what is, in reality, a glorious page in Ireland’s struggle for freedom. For these republican soldiers kept the idea of a separatist Ireland to the forefront against tremendous odds. Fighting anti-Republican and enemy forces on three fronts, on English soil and in the six and twenty-six counties. These men were not concerned with a man’s creed, whether he was Protestant, Catholic or Dissenter. They knew of only two classes of people in Ireland. Those who wished to maintain the British connection, and those who were determined to break that connection. Those who gave their allegiance to the invader, England, and those who gave their undivided allegiance to the free republican nation proclaimed in arms in 1916, and ratified by the votes of the people of all Ireland in 1918 and 1921.

“Their primary aim was the same as Connolly’s when he marched into the GPO on that Easter Monday to fight. And in his very last testimony of republican faith he bore his martyrdom to emphasise at his court martial why he fought. ‘We went out,’ he said, ‘to break the connection between this country and the British Empire and establish and Irish republic.’ How can anyone possibly overlook the courage and the suffering of a small dedicated band, many of whom are here today?

“A period that cost the lives of twenty-six soldiers of the Irish Republican Army, nine by execution in England, Belfast and the Twenty-Six Counties, five in gun battles with enemy forces and the remainder on hunger-strike or in the prisons. Yet, until recently, there seems to be this deliberate blackout of that glorious period. Could it be that it is so fashionable to be tinged a deep red, to be militantly anti-British in the Forties, as Barnes and McCormick and their comrades were, is now considered to be tantamount to being dubbed fascists? These men were not fascists, nor were they Communists, nor murderers as their enemies allege them to be. They were simply guilty of the unpardonable crime of being Irish patriots, imbued with a deep love of Ireland and her cause of freedom.

“Today, in many places, pure and raw patriotism is frowned upon. As is adherence to the policy of non-compromise and force. Indeed, one is now expected to be more conversant with the teachings of Chairman Mao than with those of our dead patriots. Barnes and McCormick were not intellectuals, they were just ordinary working class lads who looked upon it as their duty to right Ireland’s wrong. Can we assume that most of you who are assembled here today consider their cause and their methods just and necessary? Or will you assemble afterwards, in small groups, the more progressive as some of you like to be called, and speak of these poor misguided men and then propagate your ideas as to how Ireland’s freedom can be attained without fighting, without suffering, without martyrdom?

“There comes a time in every generation when men try to re-direct the Republican Movement along a different road to that upon which our freedom fighters trod. When, Liam Mellows a few hours before he faced the firing squad, wrote about that road, he said ‘The signposts on that road are plain and broad and straight. It is the road on which Tone and all our martyrs are the guides. A road marked by truth, honour, principle and sacrifice.’ That was the road upon which Barnes and McCormick trod, even onto martyrdom.

“From the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations, said Pearse. My real hope, is from these graves of Barnes and McCormick, will emanate a combination of the old and new spirit, a spirit that will inspire men and women with the noble idealism of Pearse, the social and economic philosophy and aims of Connolly, and the fighting and courageous heart of Cathal Brugha. A spirit that will ensure the final completion of the task which our martyrs were compelled to leave unfinished. That is how Barnes and McCormick can best be honoured. That is how they would wish to be honoured because that is why they lie in a martyrs grave today.”

Jim O’Regan

The other keynote speaker at the graveside was Jim O’Regan, Cork IRA veteran who had fought for the Spanish Republic with the International Brigade. He had also taken part in the IRA campaign in England and was arrested at the same time as Peter Barnes, as he recounted in his oration:

“A chairde on the morning of the 7th of February, in the dark year 1940, two gallant soldiers of the Irish Republic, James McCormick from Mullingar and Peter Barnes of Banagher, stood on the gallows in Winson Green jail in Birmingham. They were about to die at the hands of their enemies, surrounded by their enemies, in the gloomy atmosphere of an English prison. It is easy to visualise the thoughts that must have been going through their mind in those last hard moments of their lives. They knew now that never again would they see their native land. They knew now that never again would they see all those who were dear to them. They knew now that never would again would they meet their comrades in the fight for freedom.

“And now a generation has passed and twenty-nine years later, we stand at the grave of Peter Barnes and Joseph McCormick, who at last have been laid to rest in the land that they loved and served so well. On behalf the Republican Movement, and indeed of the entire Irish people, I thank the committee who have been responsible for this wonderful achievement.

“I have known many Volunteers who operated with James in the Midlands at that time. They were all deeply impressed by him. They called him an outstanding volunteer, extremely reliable and very efficient.“Peter, who was older, had joined the Fianna in 1921 and was a mere youth a few years later when he joined the Irish Republican Army. He was a very careful operator. In actual fact his presence in England was completely unknown to the police. But alas he was betrayed by an informer, an Irish one at that. He was searched, his lodging searched and nothing whatever was found on him but they knew they had their man as a result of an informers information. And they found shampoo powder in his room and they said that that was an explosive substance and they held him on that charge.“The following morning three of my comrades and myself were betrayed by the same informer and brought to Brixton Prison. Again, on numerous occasions during the following weeks both Peter and the four of us were brought to court and remanded. I had many opportunities of having conversations with him. It was I who told him of the informer. On a number of occasions when we were going to the police courts, the police informed us that one of us would be hanged for the explosion at Coventry. I discussed this with Peter and pointed out that though it would be more than difficult for them to prove because all five of us were …..two hundred miles from Coventry.

“And one night…came the tramp of many feet coming up the iron staircase in Brixton where we were, it was a large wing and they had cleared it out of ordinary prisoners to keep about a dozen of us who were there. We were closely watched and there was a large number of unoccupied cells, on each one of the ones we occupied. But yet we knew the actual situation of each of the cells of our comrades. And one night we heard the stamp of heavy feet coming up the iron staircase of police and warders coming up the stairs and then I knew they were going in the direction of Peter’s cell. I heard the door open, a few minutes passed and then they moved on…Their time began at the end of that year and on the 14th December they were sentenced to death…“In an English prison, surrounded by hundreds of armed soldiers and police, they marched proudly out to die. And their names will forever be linked with Allen, Larkin, O’Brien, Barrett, Casement, O’Sullivan and Dunne. In every generation, our noblest sons and daughters have laid down their lives for the freedom and independence of our country...

“So let us swear by these martyrs graves that will end the fight in our lifetime. And when that day comes, the day of victory, let us return here to honour the men who made that victory possible. For here lie the real architects of Irish freedom. And by their graves promise to build a state worthy of their noble sacrifice. Welcome home Peter. Welcome home James. May God give eternal rest to your most gallant souls.”

The split that Jimmy Steele hinted at was to be precipitated by the cataclysmic events in Belfast and Derry in August 1969, just a few weeks after the Mullingar funeral. Peter Barnes and James McCormack were re-interred on 6 July 1969, 50 years ago.

See also: Jimmy Steele – The life of a Belfast republican

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures