30 January 2019

Ireland at heart of crisis

A century later Ireland is again at the heart of a constitutional crisis in Britain

What if the EU had refused to acknowledge the Leave result, banned Parliament and sent troops to England to impose a reign of terror? That is precisely what the British government did in Ireland 100 years ago when we voted for independence.

Brexit is not the first time that Ireland has been at the heart of a political and constitutional crisis in Britain. On and off from 1886 until 1922 the 'Irish Question' was high on the agenda of British politics and caused deep divisions within and between parties. The question made and broke governments.

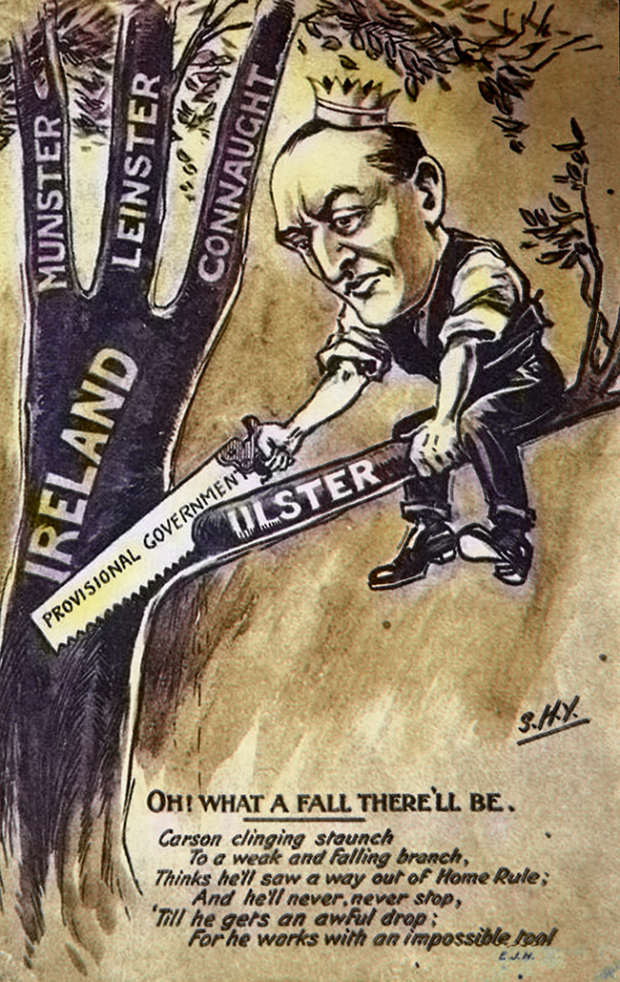

British Prime Minister Gladstone tabled Home Rule bills in 1886 and 1893. But a significant section of his Liberal Party was opposed to Home Rule and defected and Gladstone resigned in 1894. The Tory Party is still officially called the Conservative and Unionist Party and in government from 1895 until 1906 they politically buried Home Rule. The general election of 1906 saw a Liberal administration returned. This reforming government clashed with the Tory-dominated House of Lords in 1909 when the 'peers of the realm' refused to pass the budget. Following a general election in 1910 the re-elected Liberal government decided to end the power of veto of the House of Lords which was threatening to block its programme, including Home Rule.

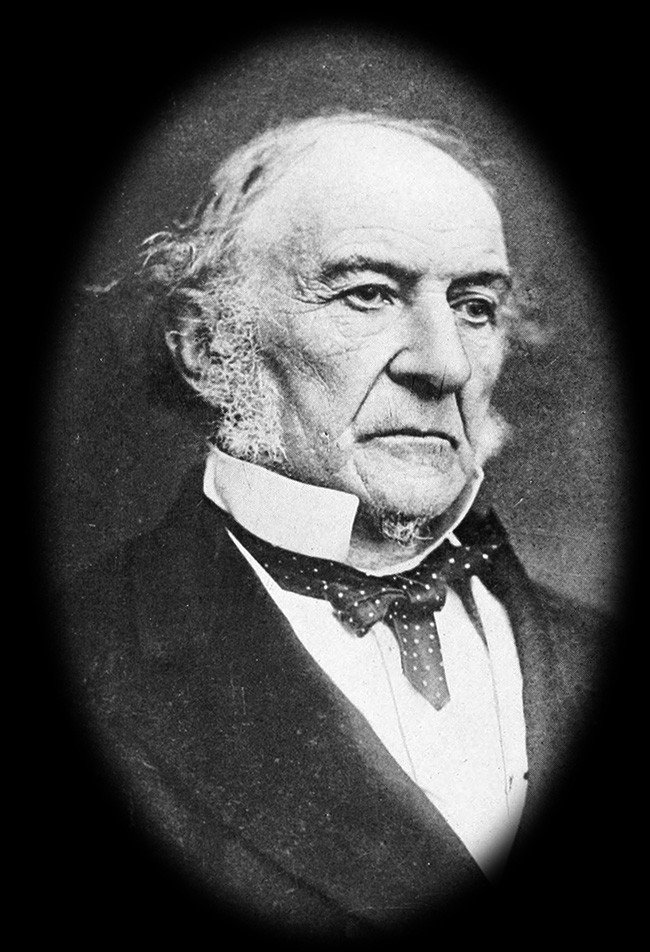

• British Prime Minister Gladstone

The Liberals seemed to have averted a full-blown constitutional crisis by simply appointing more Liberal peers and packing the House of Lords - a very British solution to a very British problem. But further crisis loomed when the Lords blocked Home Rule and joined with the Ulster Unionists in armed threats to topple the Liberals by force if Home Rule was introduced after the expiry in 1914 of the Lords' time-limited power of delay (as opposed to full veto). This constitutional crisis escalated to such an extent that King George V was drafted in to host a conference. The 'solution' brought forward by British Prime Minister Asquith was the Partition of Ireland. Talks about where to draw 'the line' were still going on when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo in July 1914. Winston Churchill famously described the scene in the British corridors of power where maps of Ireland were replaced with maps of the Balkans.

Ireland did not loom large again in British politics until after the 1916 Rising. Lloyd George replaced Asquith as Prime Minister in a war Cabinet which by then included the Tories. The Welsh Liberal leader was not to know that there would never again be a Liberal government or a Liberal Prime Minister, as that party was crushed between the regrouping Tories and the rising Labour Party. The Irish crisis was one of the mortal blows that led to ‘The Strange Death of Liberal England’, as George Dangerfield entitled his political history of the period.

Lloyd George’s Government faced a dilemma on Ireland. They were under domestic pressure to tighten repression, impose Conscription and whip the Irish into line. But the United States had entered the war on the British and French side in 1917 and Lloyd George wanted to keep America sweet in the long period between US entry into the war and the sending of its forces to Europe in numbers large enough to be decisive against Germany. So he had to perform a balancing act and fight a sharp propaganda war against the Irish in the USA.

With the Allies victorious in November 1918 pressure was off the British and in 1919 they blocked the newly elected Dáil Éireann government from receiving a hearing at the Paris Peace Conference. US President Woodrow Wilson's talk of self-determination of nations proved to be little more than rhetoric. At Paris the British and French Empires were fully restored and expanded, while only those new states that suited the Allies' strategic interests were allowed to emerge - for example Poland and Czechoslovakia but not Ireland or India. (This was what later prompted Irish Republican Liam Mellows to describe the League of Nations as the 'League of Robbers').

It was the resistance of the Irish people, with the support of the Irish diaspora in North America and elsewhere, that eventually forced the British government to the negotiating table in 1921 to re-open the constitutional question. But the British had a huge international advantage. They were under no pressure from the White House, with Wilson pro-British anyway, and with the US Congress opposed to his League of Nations. The British Empire was, seemingly, at its zenith, and with Lloyd George having set the agenda with his Partition Act in 1920, almost any scheme of autonomy for the 26 Counties could be presented internationally by the British as a generous offer. The Irish delegation succumbed to this pressure and signed the Treaty in December 1921.

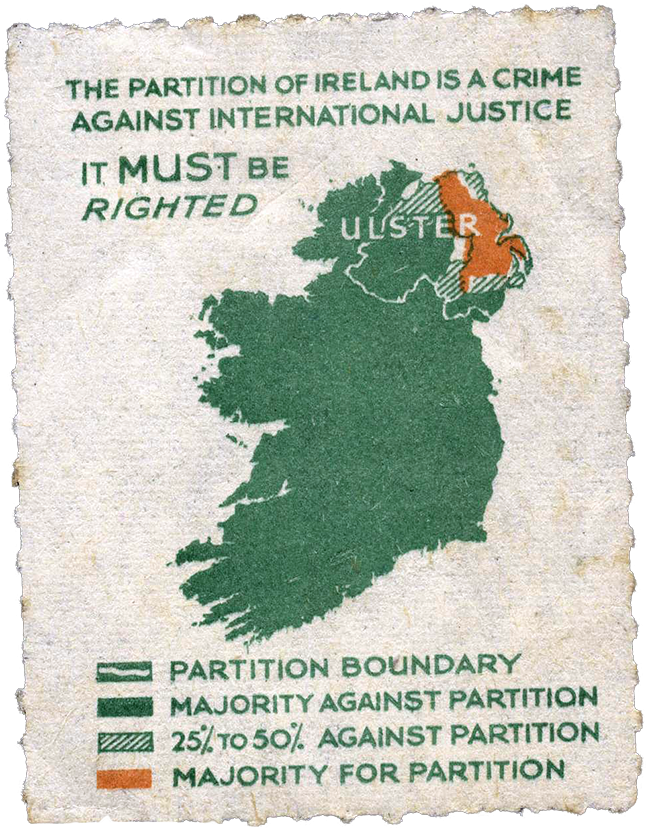

For the second time since 1910 the British government had averted a constitutional crisis in Britain, a crisis with Ireland at its heart. The price for Ireland was Partition, a bloody counter-revolution and two states, one deeply sectarian, the other deeply conservative, in a status quo that lasted for nearly 50 years until the pot boiled over in 1969.

• Lloyd George and Churchill

Roll on the clock to 2019 and the parallels are fascinating. Once again British politics is in turmoil, parties are divided internally, constitutional questions regarding Parliament, Scotland and, most of all, the Partition of Ireland are at play. The British border in Ireland is at the heart of the matter. Once again a Tory government is in league with Ulster Unionists and this has led directly to the 'backstop' dilemma. The refusal of the DUP and its Brexiteer allies to allow the Six Counties to be treated differently to Britain after Brexit creates a perfect dilemma - the British government cannot deliver a full-blooded Brexit without treating the Six Counties differently and it can only maintain the constitutional fiction of 'our United Kingdom' by delivering a much diluted Brexit.

The con-trick of Partition which the British government used ruthlessly in 1921 to maintain its grip on Ireland has now come back to haunt it as it seeks to escape from what it sees as the grip of the EU. British politicians might ponder another parallel. What would their reaction have been if, in 2016, when the Leave side won the referendum, instead of recognising the result and entering negotiations, the EU refused to acknowledge it, banned Parliament and sent troops to England to impose a reign of terror? That is precisely what the British government did in Ireland 100 years ago when we voted for independence.

But unlike 100 years ago, international factors are now running strongly against the British government. The EU has set its face against a hard border in Ireland. The determination of the British government to press ahead with Brexit regardless of the consequences for Ireland has won it no friends internationally, to say the least. Will the EU hold its line? At the moment all the indications are that it will do so.

Few could have predicted that the Partition of Ireland would re-emerge as a huge issue in British and international politics as it has done with Brexit. But Irish Republicans have been consistent, firstly in arguing that Partition was wrong and undemocratic from the start, and secondly, in saying that no form of Brexit is good for Ireland.

The wheel of history has turned full circle and now is the time to revisit the failed constitutional arrangement of Partition, devised and imposed on Ireland to serve British domestic political interests. The best way to extricate Ireland from the Brexit disaster and from the Partition dilemma is to hold a referendum on Irish Unity, as provided for in the Good Friday Agreement. Let the people of Ireland North, South, East and West decide whether we want to live together as a democratic unit which will determine for ourselves our constitution and our relationship with the EU and with the wider world.

And if we do indeed vote for Irish Unity, it just might help the people of England, Scotland and Wales to sort out their own constitutional affairs as well.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures