30 September 2018 Edition

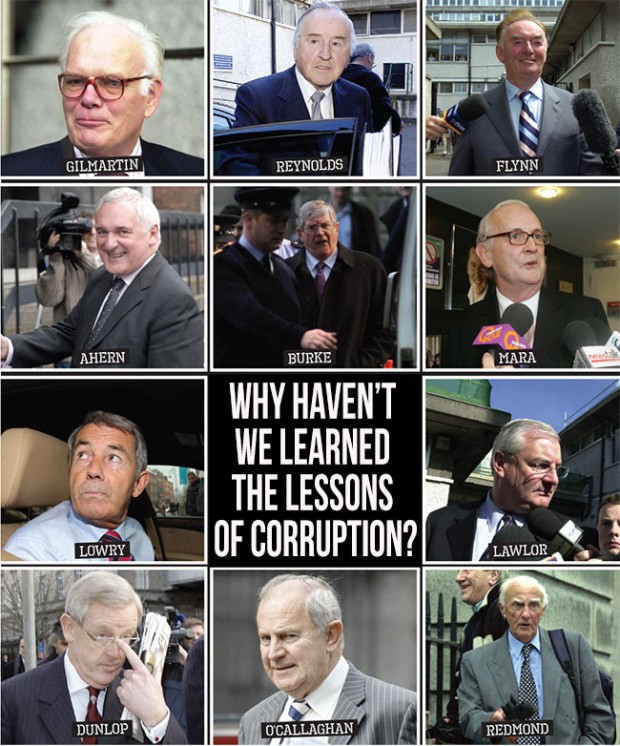

Why haven’t we learned the lessons of corruption?

The seedy truth of corruption in the Irish political elite

Frank Connolly’s investigative journalism, published in the Sunday Business Post and a TV3 documentary led to two separate tribunals of inquiry being formed. His revelations led to a range of ministerial resignations including that of former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern. Here for An Phoblacht Connolly reflects on the events that led to the formation of the Flood and Morris Tribunals.

It was around this time in summer 20 years ago when I first made contact with the late Tom Gilmartin. I got his number through the former Taoiseach, Albert Reynolds, who was aware that the property developer, based in Luton, had serious complaints about the manner in which he had been treated by politicians and others when he tried to do business in Ireland some ten years previously.

When I put down the phone after the initial 50-minute conversation, I turned to the then editor of the Sunday Business Post, Damien Kiberd, and said that “if half of what this man claims is true we are in for a rough ride”. In journalistic terms, what Gilmartin alleged was rocket fuel which could potentially embroil some of the most senior political and business figures in the country including Reynolds himself, the then Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, the EU Commissioner, Padraig Flynn, cabinet members and senior public servants in corruption allegations.

By the summer of 1998 the tribunal into planning and payments, chaired by retired High Court Judge Feargus Flood, had yet to open formal public hearings and its legal team was busy gathering evidence to support the unproven claims that had led to its establishment in late 1997. It was prompted after we published the story of an alleged payment of at least £40,000 in cash to then Fianna Fáil government minister, Ray Burke, during a general election campaign in June 1989.

• Retired High Court Judge Feargus Flood

The story emerged from a disgruntled former company executive, Jim Gogarty, who told me he was present in Burke’s house when two businessmen each handed the politician a bag of cash containing £40 grand. The payment was in order to buy Burke’s assistance in getting re-zoning for a large tract of land in the politician’s Dublin North constituency which the businessmen hoped to develop for housing.

“Will we get a receipt for this?“ Gogarty asked as they travelled to Burke’s home in Swords to close the deal. “Will we fuck,” one donor famously replied.

For many months we were unable, for legal reasons, to name any of the personalities involved in this unravelling story although since late 1995, when I met Gogarty for the first time at his home in Sutton in north Dublin, we had been publishing the claim that a senior serving politician had accepted a massive bribe in 1989.

As the general election approached in June 1997, with Bertie Ahern expected to lead Fianna Fáil into government for the first time, the party leadership and its handlers became increasingly nervous as to when and how the Sunday Business Post would identify the politician involved.

In an off the record briefing just days before polling, the FF media bully in chief, P J Mara told me he knew we were talking about Ray Burke but that anything he got in 1989 was a contribution to his election campaign and we would be sued into bankruptcy if we suggested anything else in the newspaper.

On the day of the election I met Ahern celebrating his anticipated victory in his local pub near Marino and he asked me what the story was all about. I told him about the cash handover to Burke eight years earlier and that we had strong evidence to back it up.

“I won’t have a fucking Michael Lowry in my cabinet,” he told me in reference to the controversy surrounding the former Fine Gael communications minister and the recent award of the second mobile phone licence to Denis O’Brien. I said all the information he needed was in Gogarty’s house in Sutton, a ten minute drive up the road.

Less than a month later, after Ahern claimed that he “had climbed every tree in north Dublin” to establish the truth of these allegations, now being reported across the media, Burke was appointed as Minister for Foreign Affairs. Less than six months later he resigned from office and the tribunal was announced by Ahern into corruption allegations in the planning system in Dublin.

I was not flavour of the month with the government and as the Gilmartin story gained legs into the Autumn of 1998, more sensational allegations emerged about payments made to other FF figures and about the tribunal’s investigation into them. The political temperature and pressure on the coalition government, which included the Progressive Democrats, increased.

• Tom Gilmartin

In January 1999, Flynn made a dramatic and ill-fated appearance on the Late Late Show during which he made disparaging remarks about Gilmartin and complained about how difficult it was to run three homes – in Brussels, Dublin and Castlebar. Gilmartin released the copy of the cheque he made out for £50,000 in 1989, which was intended for the party. He handed it to Flynn who was Environment Minister and who made sure that it ended up circuitously in his personal bank account.

Liam Lawlor, the influential west Dublin Fianna Fáil TD and head of the Oireachtas Ethics committee, no less, had taken buckets of money from the company with which Gilmartin worked but had failed to declare it to the Revenue authorities. By the time the tribunal was finished its inquiries it unearthed over 100 offshore accounts held by Lawlor and stuffed with monies given to him by an array of businessmen and developers in Dublin.

Former FF press officer and PR man, Frank Dunlop had received some £1.8 million to assist with the plans of Gilmartin’s former business partner and Cork developer, Owen O’Callaghan, to build the Liffey Valley Shopping Centre at Quarryvale in west Dublin. Dunlop used some of the money to pay bribes to almost one third of the members of Dublin County Council.

The former Dublin assistant city and county manager, George Redmond, had been a key figure in blocking Gilmartin’s plans and his nefarious role was exposed when he fell into the arms of the Criminal Assets Bureau as he arrived in Dublin Airport from the Isle of Man with over £300,000 in cash and cheques stuffed in his suitcase in February 1999.

Gilmartin claimed that he was hit by an unidentified man for a £5 million payment (to be lodged offshore) in Leinster House in February 1990 just after he emerged from a meeting with Charles Haughey and almost his entire cabinet.

Finally, Ahern bit the political dust when the tribunal uncovered monies he had stashed in various bank accounts when he was finance minister in the late 1990s including a cash lodgement for $45,000. His explanations of dig outs and winnings on the horses did not wash and he resigned in 2008 after his fabrications stretched the credibility of the tribunal and the public beyond breaking point. Along the way, there were serious legal and other threats made to the Sunday Business Post to desist from following the money trail that led to Ahern’s political demise.

In the intervening years, I discovered a litany of wrongdoing in the Garda Division in Donegal, courtesy of courageous people like the McBreartys of Raphoe, the Divers of Ardara, Sheena McMahon of Buncrana and Frank Shortt of Redcastle.

From 1999 to 2001, we ran details of the extraordinary behaviour of police officers in the Business Post and TV3, for which I made a series of documentaries on these Donegal corruption stories. The Garda chiefs in Dublin managed their best to keep a lid on the unfolding scandals with the assistance of willing security correspondents in the other mainstream media. They reckoned that no-one would believe that members of the force would plant explosive type materials in a shed, close to where the Orangemen were due to march in Rossnowlagh, or at a television MMDS mast where protests were being held near Ardara, or illicit drugs in Shortts pub on Inishowen. Shortt spent three years in jail after he was framed by two members of the gardaí.

But it was all true and by 2002 another tribunal was established to investigate allegations of wrongdoing in the Donegal Garda division chaired by Judge Freddie Morris. Its lead counsel was a lawyer called Peter Charleton.

As we look back 20 years on, it is safe to say that if the lessons of endemic corporate, political, and garda corruption had been heeded back then we would not be where we are today.

Frank Connolly is an investigative journalist who has recently authored two best-selling books, Tom Gilmartin - the Man who brought down a Taoiseach (Gill & Macmillan 2014) and NAMA-land (Gill Books 2017). He is Head of Communications with SIPTU.

Ireland’s shameful 'Golden Circle' of corruption and privilege

The first public Dáil inquiry began in 1925. The issue was food prices. Since then there have been 34 tribunals including the ongoing Charleton Tribunal based on the disclosures of Garda whistle-blower Maurice McCabe. These tribunals have dealt with issues such as the Kerry Babies scandal, the Whiddy Oil disaster, illegal money lending and Hepatitis C infections.

In most cases, the tribunals have attempted to grapple with and investigate the failure of the Irish state and its agencies to behave lawfully and in the interests of the Irish people. Four of the tribunals have dealt with the issue of Garda malpractice. Other than the current Charleton Tribunal there were the Kerry Babies, the Barr and Morris Tribunals.

However, beginning in 1991 there were a series of tribunals that focussed on the behaviour of Irish politicians and their links with Ireland’s business community. Beginning with the Beef Tribunal in 1991 these were the first steps in the uncovering of a so-called ‘Golden Circle’ of privilege and power in Irish society. We give a rundown of the most recent and serious of these tribunals.

Not included in these lists are the range of other reports and studies into other failings of Irish political society. The Ferns Report on clerical sexual abuse in the Diocese of Ferns, the Ryan Report on child abuse at religiously run institutions, or the Murphy report into sexual abuse in the Dublin Archdiocese are not included in the 34 tribunals.

Also not included are the other Commissions of Investigation into issues such as the 1974 Dublin Monaghan bombings, the Irish banking crisis, or the Mothers and Baby Homes Commission. Taken together these inquiries are a powerful indictment of the failings of official Ireland in the decades since independence.

Beef Tribunal: 1991 to 1994

The Tribunal of Inquiry into the Beef Processing Industry came into being to hold together a Fianna Fáil Progressive Democrat coalition government formed in 1989. Its revelations led to the collapse of that government in late 1992, with a resulting general election.

Running for 226 days it exposed systematic malpractices within the Irish beef industry. Including tax evasion, abuse of EU and Irish government funding schemes, a failure of industry regulation and a series of allegations made in the Dáil of specific political influence by those within the industry.

The inquiry was started after World in Action an ITV current affairs programme broadcast an investigation into the Irish beef sector.

Flood/Mahon Tribunal: 1997 to 2012

Estimates of the costs of the Flood/Mahon tribunal are as high as €250 million. The Flood Tribunal began as a result of the claims of a whistle blower James Gogarty alleging payments to Fianna Fáil minister Ray Burke and others in return for favourable planning decisions. The tribunal grew over the years, with Justice Flood retiring and replaced by Justice Mahon. In all there were 900 days of testimony and questioning.

Fianna Fáil politicians Ray Burke and Liam Lawlor and former Dublin City Manager George Redmond all served prison sentences as a result of the tribunal’s investigations.

McCracken Tribunal: 1997

The McCracken Tribunal began in February 1997. Its purpose was to investigate payments by then Dunnes Stores Managing Director, Ben Dunne, to former Taoiseach Charles Haughey and Fine Gael Communications Minister Michael Lowry.

McCracken found that Lowry had received payments of hundreds of thousands of euro from Dunne and had attempted to evade tax diverting the monies through off shore accounts or using them as payments for the rebuilding of his family home.

He recommended that all politicians should be able to demonstrate tax compliance and that failure to disclose all political donations should be made a criminal offence.

Moriarty Tribunal: 1997 to 2011

Better known originally as the ‘Payments to Politicians Tribunal’, this inquiry began over revelations that former Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Charlie Haughey and Fine Gael minister Michael Lowry had been in receipt of secret payments and had been evading tax on undisclosed income. It broadened into a much larger inquiry involving many more politicians and most controversially began to focus on the awarding of Ireland’s second mobile phone licence in 1996. The licence was won by a consortium led by controversial business man Denis O’Brien.

• Michael Lowry

Ansbacher Report: 1999 to 2002

Costing €3.2 million, The Ansbacher Report published in 2002 revealed the existence of a secret bank with 190 account holders. The bank was run by Des Traynor, who had been former Taoiseach’s Charlie Haughey’s financial adviser. There were no prosecutions, but over €18 million in taxes were subsequently recovered by the Revenue Commissioners.

Morris Tribunal: 2002 to 2008

The Morris Tribunal was established on the basis of a series of allegations made against the Garda Síochána in Donegal. It was the work of investigative journalist Frank Connolly that was the catalyst for the establishment of the inquiry.

The Tribunal found that Garda officers had fabricated finds of explosives to further their careers, and that there had been “gross negligence" on the part of senior Gardaí in Donegal. The Gardaí were also found by Morris to be negligent in their investigations into the death of cattle dealer Richie Barron in October 1996. The final report of the tribunal found that Gardaí in Donegal had waged a campaign of harassment against the McBrearty family.