3 July 2017 Edition

Erin’s Hope

150th anniversary of Fenian gun-running ship from the United States

A MEETING of Fenians, all former Union Army officers and American Civil War veterans, was held in New York on 18 February 1867 under Lieutenant Colonel James Kelly to draw up plans for a military expedition to Ireland in support of a rising expected in the near future.

Congressman James E. Kerrigan was in charge of the preparations for this expedition. Even though word filtered through in March that the Rising had not been successful, plans continued. It was obviously hoped that the thousands of Irish Republican Brotherhood members who mobilised on 6 March and those who never mobilised would still be waiting in readiness for renewed leadership to strike the blow against the British and to declare the Republic.

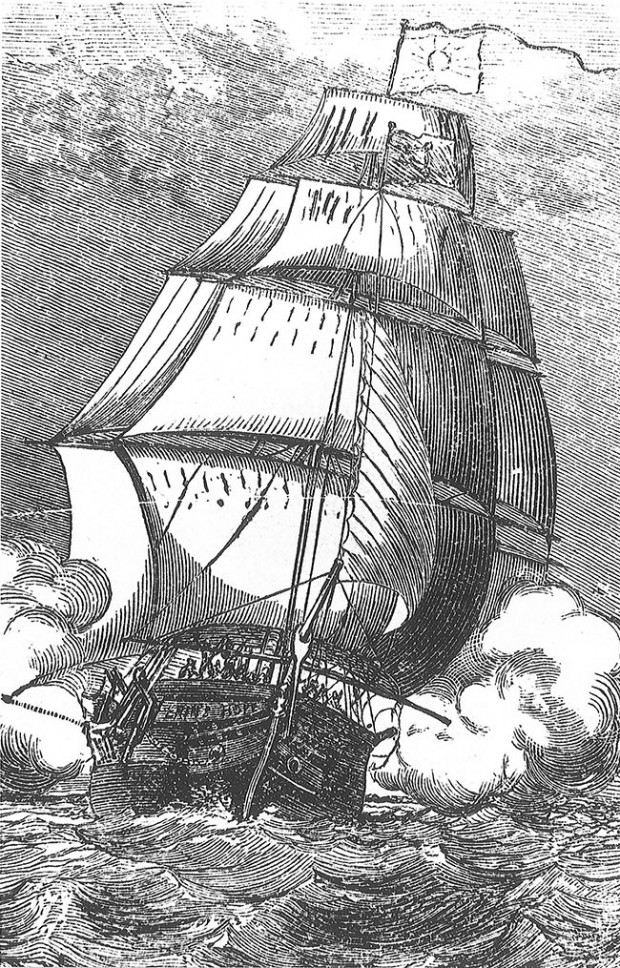

An 81-foot, two-masted, square-rigged, 200-ton brigantine, the Jacknell (spelt "Jacmel" in some reports), built in 1861 in Medford, Massachusetts, was bought by in 1866 by Charles F. Blake from the US marshals who had confiscated it in Panama due to non-payment of seamen’s wages and fines.

In March 1867 it was berthed in New York when a huge haul of armaments from the recently-ended US Civil War was transferred aboard in crates labelled as pianos, sewing machines and wine in casks.

The arsenal included 5,000 rifles, five million rounds of ammunition, three 6lb artillery pieces, and 1,000 sabres.

When the Jacknell with its crew of five set sail from New York on a course for Cuba to avoid arousing suspicion, it had carpenters on board. They were working away feverishly, making alterations to the vessel for the long voyage that lay ahead. The carpenters were landed ashore as soon as possible when the living quarters were completed.

They headed to Boston in a circuitous route to avoid raising suspicions of the US Customs, which could have scuppered the mission in trying protect the declared neutrality of the United States. It was at Sandy Hook that Captain John Kavanagh, the rest of the cargo and some 40 Fenians (mainly veterans of the Civil War) came aboard under the cover of darkness.

Captain Kavanagh had been appointed commander of the Jacknell in April 1867 by the IRB’s Chief of Naval Affairs, Captain John Powell, in a letter setting out his mission. The objective was to be the first ship under an Irish flag to set sail for Ireland with republican soldiers and armaments since Wolfe Tone’s landing from French warships in Donegal in 1798.

A new flag is hoisted

The Jacknell sailed away on its designated course, changing direction only the next day when clear of the reach of US Customs patrols. It wasn’t till just over a week later, on Easter Sunday, 21 April, in mid-Atlantic that the ship’s exact course was revealed to all aboard. The ship was renamed Erin’s Hope to huge applause. A new flag, a sunburst, was hoisted and they set sail for the Donegal coast, which was believed not to be as well-patrolled by British naval vessels as other parts of the Irish coast.

Later than anticipated, on 10 May they sighted land. For several days, the Erin’s Hope waited off Donegal Bay for a signal from shore but the only signals they got were from the coast guard enquiring as to their intentions. Local fishermen and pilots also visited them and all the while the men on board had to hide below decks.

On 23 May, Captain Kavanagh and two Fenians, Colonel Doherty and Lieutenant O’Shea, were sent ashore at Steedagh, near Sligo, to try and make contact with local Fenians. Captain Kavanagh hoped to land the rest of the detachment, take Sligo, muster support and stimulate a general uprising.

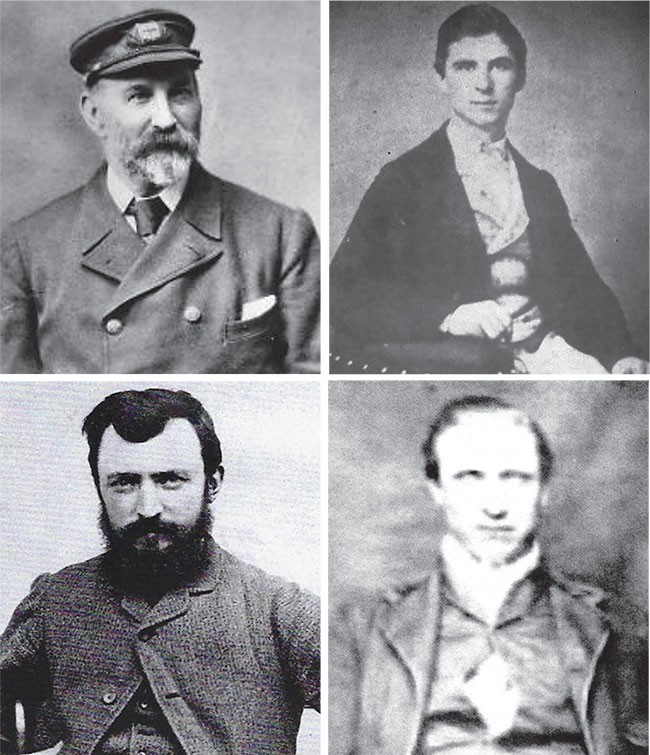

• (clokwise) Captain of Erin’s Hope: John Kavanagh, William Lomasney (Captain Mackay), Fenian Daniel Buckley and Richard O’Sullivan Burke

•

Tensions

The delay in disembarking caused tensions which spilled over and three men were injured. Two sailors were shot (James Nolan and John Smith) and a Fenian, Daniel Buckley, was injured. A local ship’s pilot came on board and had to be detained to protect the purpose of the mission.

The two disembarked Fenian officers returned with Richard O’Sullivan Burke, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who explained the grave situation in Ireland. Due to the failed rising, movement was severely curtailed and communications totally hampered.

Burke suggested they sail towards County Cork, where it was hoped that they could meet up with other Fenian officers such as William Lomasney (Captain Mackay) who were engaged in an ongoing guerrilla warfare campaign across southern Munster, attacking coast guard stations, procuring weapons and other activities.

Before setting sail on 24 May, the two wounded sailors were put ashore under the control of Patrick Nugent so they could receive treatment. Richard O’Sullivan Burke also went ashore along with the two Fenian officers, Doherty and O’Shea. At this stage the British Royal Navy fleet and the coast guard been warned of the activities of a suspicious ship and were en route to intercept them when Captain Kavanagh decided he couldn’t await his officers’ return and set sail again.

From 27-30 May, despite the dangers, the Erin’s Hope cruised along the Cork coast in a forlorn quest for the signal. Even a near-boarding from the coast guard didn’t deter Captain Kavanagh and his detachment from continuing with their mission. On 31 May, the weather began to blow and the ship had to head eastward, being chased for a while by a British ship.

The next morning, 1 June, saw the Erin’s Hope arrive at Helvic, off Rinn an gCuanach on the Waterford coast.

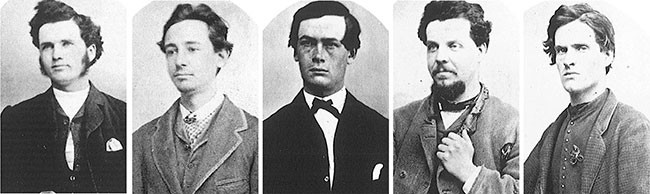

• Some of the Erin’s Hope members: Augustine Costello, Michael Walsh, John Hanley, Bryan Courtney and Nugent (first name not known)

‘Square-toed foreigners’

Despite a fog, they managed to communicate with local fishermen and Páid Mór Ó Faoláín agreed to land 32 of the Fenians later under the cover of darkness for £2. Thinking that the fog would give them cover, a landing was attempted early at Cé Bhaile na nGall (Ballinagoul Pier).

An alert coast guard and the local Royal Irish Constabulary arrested 26 of the “square-toed foreigners” almost immediately despite them having split into groups of threes or fours in the vicinity. Some succeeded in evading capture, including one who was hidden by relatives locally and eventually made his way back to America under an assumed name.

It was another few days of cat and mouse off the Irish and the English coasts for the Erin’s Hope before the crew and the remainder of the expeditionary force on 6 June set sail for the United States again with their munitions cargo nearly fully intact.

Back in Ireland, the captured men were being cheered as they were being transferred in seven carriages under armed escort by RIC police constables and 16 soldiers from the British Army’s 17th Regiment from Dún Gharbháin (Dungarvan) to the more secure Waterford Gaol.

More crowds added to a carnival atmosphere in Waterford City, where Resident Magistrate H. E. Redmond and another 30 constables armed with breech-loading rifles were forced to increase the security detail.

‘Obnoxious’ British agents

On 10 June, two British agents, J. J. Corydon and Talbot, who had infiltrated the Fenian Movement (and described by the Waterford News as “obnoxious characters”) were brought from Dublin to the jail to identify the captives.

Three nights later, when another unit of IRB Volunteers captured in Cork were being brought to Waterford, their armed guard came under attack with such ferocity that even when British reinforcements arrived it didn’t quell the crowd. The rioters were described as being made up of “salters and labourers with a sprinkling of fisherwomen who would prove the most formidable of assailants”. A bayonet charge was ordered and a local man named Walsh was stabbed through the heart; several police and locals were severely injured.

The captured men were then sent to Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, on the train next morning, where they were met by two full troops of cavalry of the 9th Lancers and a large detachment of mounted police.

Most of the Fenians were Irish-born but naturalised US citizens and hadn’t committed any crime on Irish soil under Britain’s jurisdiction (the evidence for an insurrection had managed to sail away) but with habeas corpus suspended due to the rising in March they could indefinitely detain the men or at least until habeas corpus was reinstated.

With both the British and US governments trying to repair relationships that had been strained during the US Civil War, they could have done without the furore of imprisoned US citizens in Irish jails so most of the men were released quickly on condition that they leave Ireland and not return. Within six or seven months, only eight prisoners remained incarcerated.

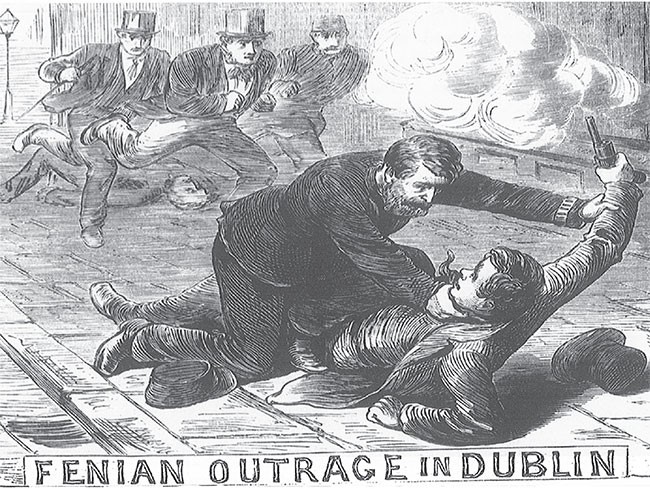

• 1671: A Fenian assassination squad at Hardwicke Street, in Dublin's north inner city, shot Thomas Talbot, a police informant against the Fenians

‘As long as I have breath . . .’

It was to be some months before the authorities could cobble together evidence against them, and then it was mainly to come from one of their own. Daniel Buckley, who was involved in the shooting incident on board the Erin’s Hope while off the Donegal coast, betrayed his comrades and spilled the beans on the entire expedition. Some were charged with treason-felony and convicted.

Their cases were to have far-reaching effects beyond Ireland with both the US and Britain changing their laws to address the rights of naturalised citizens.

John Warren was sentenced to 15 years’ penal servitude. Augustine E. Costello, from Killimor, County Galway, was sent to Portland Prison in England to serve his 12-year penal servitude sentence, being released in April 1869.

Warren had been released in May 1868. At a huge welcome home gathering in Ballinasloe, County Galway, he stated:

“As long as I have breath, I will conspire and plot to overthrow the British Government.”

Both Costello and Warren left Irish shores for America on 30 April 1869. The Mayor of Cork held a banquet in their honour on the eve of their departure.

The British agent Talbot was assassinated four years after the mission, in 1871. Another informer in the case, William F. Milton, was shot two days after he returned to New York in August 1867 by the son of prominent Young Irelander Michael Doheny.

Of the two sailors injured in Sligo, Nolan recovered quickly but the other, John Smyth (alias John O’Connor), died from gangrene poisoning in December 1867.

The Erin’s Hope arrived back in New York 150 years ago, on 1 August 1867, having sailed over 9,000 miles in 107 days.