3 July 2017 Edition

A right to remember

• For what died this son of Róisín?

Handing me a shamrock-shaped pin adorned with a red poppy, a thick Dublin accent in a British Legion uniform asked: ‘Are you boys from the Shankill Road?’

JOHNNY McGIBBON, a Sinn Féin activist, recently spent some time in Flanders as part of a delegation organised by ‘The Fellowship of Messines’ to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Messines in the First World War.

He reflects some of his thoughts while visiting the cemeteries and former battlefields as well as attending a joint event hosted by the Irish and British governments in the ‘Island of Ireland Peace Park’.

ROW BY ROW, stone by stone, grave by grave. Well-groomed and orderly. Calm. Peaceful. A state of serene irony.

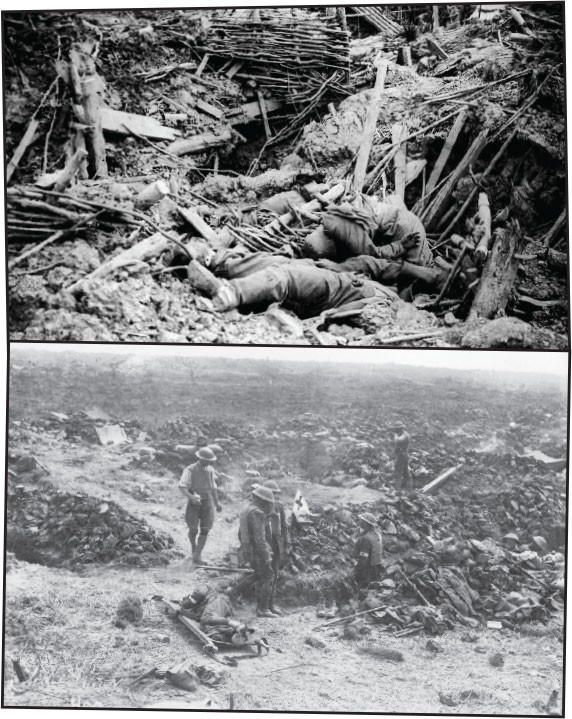

Look around Tyne Cot Cemetery and glance up at the surrounding countryside. With 100 years of hindsight, I can’t help but compare the tranquility of a sunny Flanders afternoon with the horror that surely was the Western Front in 1917.

Looking around, there are almost 12,000 headstones, of which more than 8,000 are unknown and unnamed, “Known Unto God”. To the back stands a memorial of some 34,887 names of military personnel whose remains were never found or identified. In fact, this is an overspill from those 54,896 commemorated every night at 8pm with The Last Post at the Menin Gate, Ypres.

The cemetery is speckled, tidily, with small poppy-adorned crosses, flowers and some small Canadian flags – a long way from home; further still for those New Zealanders and Australians who perished at Passchendaele.

Sitting in the ‘Island of Ireland Peace Park’ a day previously, I’m a long way from home. Britain’s Prince William, Enda Kenny and the Princess of Belgium are preceded by a joint colour party from the Royal Irish Regiment and the Irish Defence Forces. All very unfamiliar to a Lurgan man (except the RIR).

It’s all about being ‘uncomfortable’ . . . and I was.

Did I ever think I would be sitting at a joint Irish-British governmental commemorative ceremony in Belgium? You know the answer to that.

But ‘uncomfortable’ is okay.

The Irish nationalist narrative of the First World War has traditionally been a quiet one; a “national amnesia” Martin McGuinness once said. Of course we know there were volunteers who joined the British Army fighting for Home Rule; we know that the Ulster Volunteer Force volunteers enlisted in an effort to stop it. We know, also, that the nationalist argument was won at home; and, in 1918, Sinn Féin won an overwhelming electoral endorsement for national independence.

Nonetheless, tens of thousands of Irishmen died in “The War to End All Wars”. Many more tens of thousands never returned to live in Ireland. Of those who did return, undoubtedly many were ostracised, mistrusted in a revolutionary era when the Irish people took on the very empire that commanded both the 16th Irish Division and the 36th Ulster Division at the Messines Ridge.

Many returned to Ireland and joined the Royal Irish Constabulary’s Auxiliaries or the Black and Tans.

Others came home and soon joined the Irish Republican Army, Tom Barry being a famous example.

And so the complex nature of Ireland versus ‘West Britain’ absorbed me as I wondered why “An Irish Soldier of the Great War” ended up in ‘New Irish Farm’. For what died these sons of Róisín?

It wasn’t “The War to End All Wars”.

It was the war of the machine gun. It was the war of chemical weapons. It was the war that planted the seeds of further conflict.

For what died these sons of Róisín?

At Langemark Cemetery, flat stone markers surround a mass grave of some 25,000 German soldiers. And for what died they?

Following the ceremony in the Peace Park, I stood discussing the event with a loyalist who was also on the trip. A small group of people approached. Handing me a shamrock-shaped pin adorned with a red poppy, a thick Dublin accent in a British Legion uniform asked: “Are you boys from the Shankill Road?” I took the pin. “Níl ach, go raibh maith agat.”

I don’t need to wear it but I respect the right of others to do so. Respect does not need a single narrative.

There must be a right to remember – be it Messines or Loughgall.