3 July 2017 Edition

When is genocide not genocide?

• New mural on Belfast's International Wall highlighting the Tamil conflict

IN THE AFTERMATH of the war in Sri Lanka and the defeat of the Tamil Tiger guerrillas in 2009, the Sri Lankan Government has set out to systematically destroy any hope the Tamils have of establishing their own independent state. Not only that, but the Sinhalese-dominated regime has thrown a blanket of censorship, disinformation and fabrication over the military onslaught that saw as many as 70,000 Tamils – civilians as well as fighters – slaughtered.

In an attempt to break though this ‘official’ presentation of the conflict and its causes and to present their narrative, upwards of 35 Tamil exiles travelled to Belfast and Derry on 18 May – “Mullivaikkal Day” (Tamil Genocide Day) – to take part in a series of events with Irish activists.

As in the North, where the British and unionist narrative of the conflict is focused on blaming republicans, the Sri Lankan regime (with the connivance of Britain and the United States in particular) is presenting the Tamils as the transgressor.

During the day in Derry and Belfast it became clear that the struggle for Irish freedom and the Tamil struggle has similarities and parallels stemming from the dark hand of British colonial policy.

These parallels could also be seen in how the issue of remembrance and legacy are politically potent issues in the here and now.

Solidarity at the International Wall

At the unveiling of a mural on Belfast’s world-famous International Wall on 18 May, Sinn Féin members and campaigners with human rights projects, including Relatives for Justice, joined Tamil exiles to mark Mullivaikkal Day.

Sinn Féin activist and An Phoblacht columnist Peadar Whelan said:

“The links between the Irish struggle and the struggle for a Tamil homeland in Sri Lanka have their roots in British colonialism and imperialism. The strategies that were developed in Ireland to repress our freedom struggle were used in Africa, in Asia and in India, from where they extended to Sri Lanka.

“The solidarity that we Irish activists extend to the Tamil people in the painting of this mural sits alongside the solidarity and support we show to the people of Palestine, South Africa, Cuba, Kurdistan and the Basque Country.

“And in that spirit of solidarity we support your struggle for self-determination and a Tamil homeland, Tamil Eelam.”

• Aftermath of the war in Sri Lanka and the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in 2009

New Tamil mural

The unveiling of the new Tamil mural was one of a series of events organised in solidarity with the Tamil people by a group including Sinn Féin, Relatives for Justice, ex-prisoners group Coiste na nIarchimí, the National Graves Association and representatives of families killed by British state forces, including the Ballymurphy Massacre families.

Prior to the mural unveiling, a discussion held in Conway Mill heard moving testimony from Dr Tamilvani, who was in Sri Lanka as the military closed in on the Tamil Tigers in the closing days of the war in May 2009 and the areas designated as “No Fire Zones”.

These locations were designated as safe areas by the Sri Lanka Government and Tamil civilians were corralled into them reputedly for their own protection yet they became the very killing fields in which it is believed 70,000 men, women and children were massacred.

In an emotionally-charged and moving testimony she described how she witnessed “genocide” as the military directed massive firepower into the “No Fire Zones” hitting hospitals, food distribution centres and International Red Cross ships sent to evacuate the wounded.

Despite being furnished with the co-ordinates for hospitals by United Nations observers the heavy artillery bombardment rained down on these medical centres and UN positions. No one was spared.

Even with the clear evidence that the Sri Lankan armed forces deliberately shelled these safe zones, targeting civilians and medical facilities, summarily executed prisoners and raped women captives, the international community refuses to acknowledge this as genocide, as defined by the United Nations, and thus hold the Sri Lankan Government to account.

“We cannot use the ‘G’ word to describe this slaughter, these massacres,” said Tamilvani as she broke down and asked “for forgiveness from those I left behind”.

However, in an example of the positive effect the day’s events had on the Tamil activists and on Tamilvani in particular, she vowed, during the question and answer session after the showing of Callum Macrae’s documentary, No Fire Zone, that she “would write and tell the story of what happened and the story of those who were killed so the world will know”.

Parallels with Palestine

• Mike Ritchie and Andreé Murphy of Relatives for Justice, Fr Ravi, Sinn Féin Deputy Mayor of Belfast Mary Ellen Campbell, Tamilvani and Jude Lal Fernando of the Tamil delegation, playwright and activist Laurence McKeown, and Mark Thompson of Relatives for Justice

FR RAVI EMMANUEL, who travelled to Ireland from Jaffna in northern Sri Lanka to attend the commemoration events marking Mullivaikkal Day, is a quiet man whose demeanour reminded people of Fr Alec Reid.

Fr Ravi, a Catholic priest, is very clear about the objective of the Sinhalese majority government which, he says, “wants to destroy any possibility of a separate Tamil homeland with self-rule and to erase any notion of a distinct Tamil identity”.

In describing an experience of military repression, land confiscation, economic and financial impoverishment underpinned by cultural annihilation, it is clear, according to Fr Ravi, that there are parallels between the experiences of the Tamils and the Palestinian people in the Occupied Territories.

Fr Ravi said the Sri Lanka Government project is to create a ‘one nation and one state’ solution where the Sinhalese majority will swamp and eventually erase the Tamil nation.

“They are moving Sinhalese families into towns and villages that have Tamil populations as part of a policy to change the demography of the north and east, the Tamil homelands. So they are creating state-sponsored settlements designed to break the continuity of Tamil Eelam.

“They are forcing Tamil women to marry Sri Lankan soldiers and Government ministers are opening calling for soldiers to take Tamil brides.

“These unequal relationships are being forced on women who have been impoverished since the end of the war because they have lost their homes and their lands have been confiscated by the military, where in some instances they have built hotels or cleared the land for golf courses.

“In other examples the soldiers are using modern methods of cultivation to produce crops which they can sell at better prices than the Tamils. It is against this background that Tamil women are agreeing to what are, in reality, forced marriages”.

Equally, the cultural and religious onslaught against the Tamils is ongoing, with Buddhist shrines being given precedence over Tamil shrines.

“In Nainathaweevu, the military built a 67-foot-tall Buddhist statue to dominate the Hindu shrine and provocative Buddhist festivals take place under the wing of the military.

“In a lot of places they are replacing the Tamil names with Sinhalese names as they continue to destroy the Tamil national identity.”

The consequences of the military defeat saw the defeat of the Tamil Tigers and the deaths of a possible 70,000 civilians.

An estimated 22,000 people are listed as ‘disappeared’ in the aftermath of the war.

Britain’s dirty war against the Tamils

BRITAIN was – and is – a key player in the war in Sri Lanka.

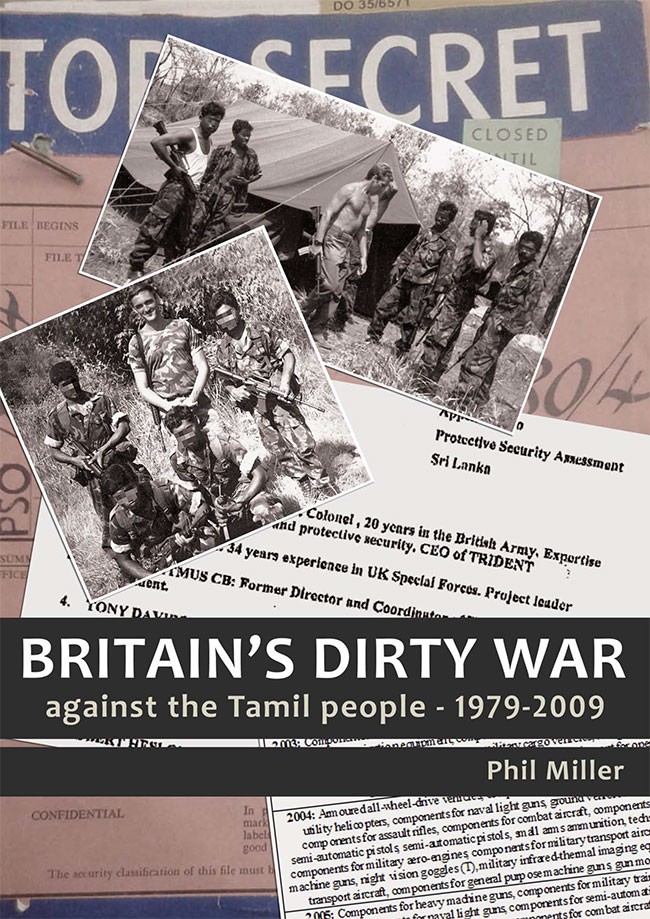

In his ground-breaking publication, Britain’s Dirty War Against the Tamil People, 1979-2009, Phil Miller traces the links between the Sinhalese majority’s policies to deny the Tamils citizenship of post-Britain Ceylon (it changed its name to Sri Lanka in 1972). Miller points out how “the different facets of the Sinhala supremacist ideology and the building of the unitary state structure were crafted by the British to further their strategic aims in the Indian Ocean”.

In an introductory timeline, Miller reveals the direct intervention of the British in the war.

In 1979, Jack Morton, a former director of MI5, went to the island and made “practical recommendations for the total reorganisation of the intelligence apparatus”.

Then, in 1983, senior Sri Lankan police officers came to Belfast to “see at first-hand the roles of the police and army in counter-terrorist operations”. They also attended an MI5 conference on “terrorism” in London and “discussed Tamil separatists”.

Further to this, beginning in 1984, British mercenaries, including former SAS members, began operating with “no objection” from the British Government. These ex-SAS troopers were employed by KMS Ltd, a private military corporation set up by ex-SAS officers in the 1970s and which trained the notorious Sri Lankan “Special Task Force”.

British counter-insurgency expert Major General Richard Clutterbuck also ‘advised’ the Sri Lanka Government.

In the early to mid-1990s, the top tier of the Sri Lanka Army was trained in Britain and the British military attaché in Colombo – with “first-hand experience in Ireland and Oman” – was a protégé of the infamous Brigadier Frank Kitson.

Britain banned the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Tamil Tigers) in 2001 and advised Sri Lanka on its “defence review”. Another British Army officer-turned-mercenary, Tim Spicer, advises the Sri Lankans on security. Like Kitson, Spicer saw active service in Ireland and was honoured by the British monarch.

Britain is also making “substantial arms sales” to the regime.

Throughout the final six months of the war, the British Government was, Miller said, “deepening its ties with the Sri Lankan police” and sent “a delegation of senior Northern Irish police commanders to Colombo as critical friends”.

This was happening as bombs were falling on hospitals in the No Fire Zones.

The world awaits the full story of the genocide against the Tamil people.