13 March 2017 Edition

The legacy of Charles J Haughey

I dismissed Haughey long ago, as did most Irish people, concluding that he was little more than a spiv – just one more in a long, depressing line of bought politicians

I GREW UP in Edenmore, on Dublin’s northside, and Charles J Haughey was our local TD but the only time I saw him in the flesh was the day he shook hands with the crowds on Springdale Road when the Dublin Marathon passed by in 1982.

I was struck at the time by his lack of height; much later by his venality.

For years, all I saw was the corruption for which Haughey was a glutton. Yet there always seemed to be something missing. The story of Haughey began and ended with Haughey, and as such it always felt incomplete.

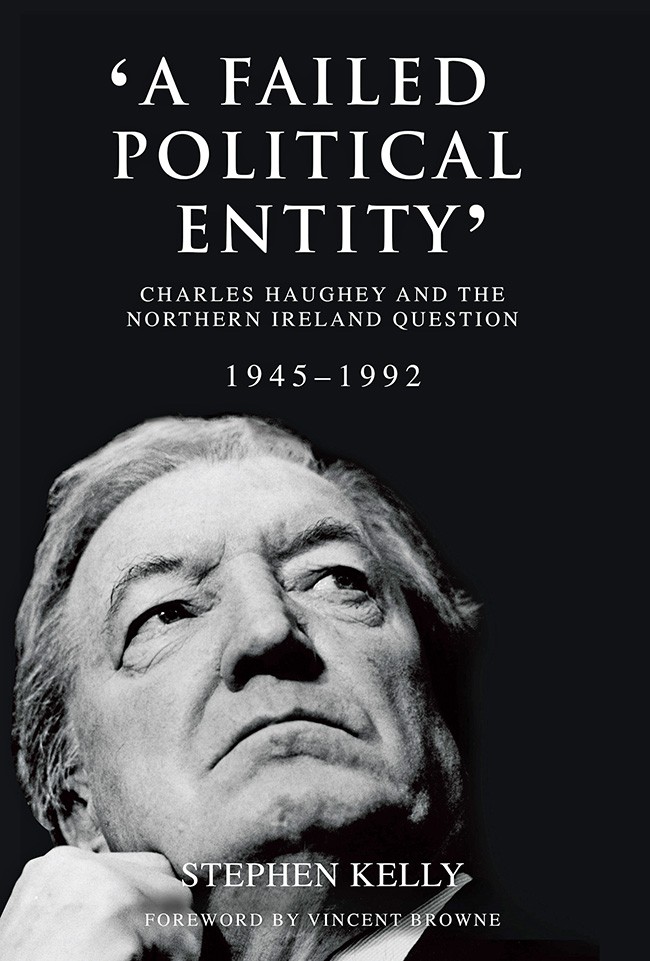

In his A Failed Political Entity’: Charles Haughey and the Northern Ireland Question, 1945-1992 (Irish Academic Press, 2016), historian Stephen Kelly asserts the genius of the man and his positive contribution to Irish society. “The facts speak for themselves,” says Kelly, who cites “free travel for pensioners and tax exemptions for artists” as among Haughey’s crowning achievements.

Not to disparage tax-free royalties, but if this is the standard by which genius is bestowed then the current Dáil possesses more intellectual rigour than Italy during the Renaissance. If free travel makes Haughey the Napoleon of Irish politics, then surely the fixed roads of Kerry make Danny Healy-Rae our Lincoln?

This is a dilemma faced by any researcher into Haughey.

The grandiose claims made about the man seem out of kilter with his seemingly sole lasting political achievement, which was to become leader of Fianna Fáil and Taoiseach after having spent ten years in the wilderness. It was a feat of some standing, no doubt, but hardly a service to the state.

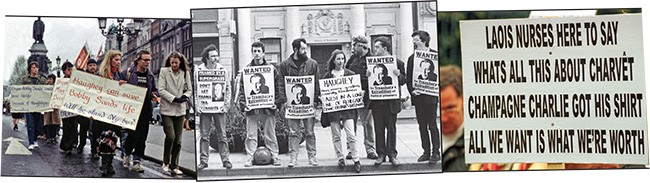

I dismissed Haughey long ago, as did most Irish people, concluding that he was little more than a spiv – just one more in a long, depressing line of bought politicians.

It is only in recent years when I began to delve into the Irish middleman class – the compradors who make millions charging transnational capital for use of the Irish state as a tax haven – that a context for this Irish Napoleon began to reveal itself.

Today, Fianna Fáil is a party of lawyers and accountants. The economic interests of those two professions are intertwined today with the tax haven model and loose regulation that the former accountant Haughey himself utilised and encouraged during his time as Finance Minister.

In the 1960s, Haughey was a firm advocate of the establishment of an Irish money market that would recycle Irish bank deposits in the state via the purchasing of Central Bank debt rather than continuing the practice of Irish banks investing primarily in Britain and starving the Irish state of much-needed credit for public infrastructure.

• Haughey failed to live up to his image as a republican and a man of the people when it really counted

He was also instrumental in facilitating foreign banks opening up in the Irish state, including the First National City Bank of New York, which opened its doors at 71 St Stephen’s Green in 1967 with the ribbon cut by Haughey. This brought Dublin into the euro-dollar market network, a quasi-legal recycling of US dollars in Europe.

It was around this time that a group of Irish economists based in Trinity College (along with lawyers, accounts and bankers) in Dublin saw the way the world was going and decided that their future lay with the Irish state opening itself up to transnational finance. The Bretton Woods Agreement was breaking down and the Chicago School of Economics was quietly taking hold.

In the 1970s, a group of Irish Government officials wanted to set up an offshore banking centre in Dublin. The Central Bank rejected the idea, saying that “it smacked of a banana republic”. Yet, by 1987, it had become part of official Irish industrial policy under the direction of the recently-elected Taoiseach, one Charles J Haughey. The financial lawyers and accountants had finally won through; and it only took 20 years.

Haughey acted as the vanguard for one side in an intra-class battle – between competing interests and competing visions within the same class for control of the Irish state and its future direction.

We should reassess Haughey not in order to change or modify the conclusions we have come to with regard to the man himself but for the light his career shines on the class interests he served and protected throughout his long and ignominious career.