16 May 2016 Edition

Thriving and striving to spread Uncomfortable Conversations – Rev Dr Norman Hamilton

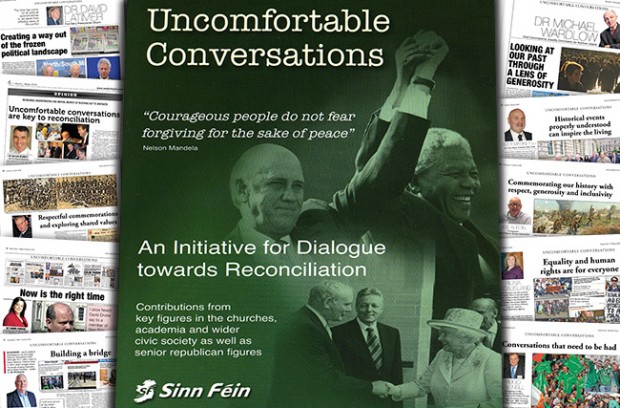

UNCOMFORTABLE CONVERSATIONS

• The Uncomfortable Conversations initiative has been ongoing since 2012

I would suggest that the lack of traction for the Uncomfortable Conversations project amongst many people outside the republican tradition lies partly in the widespread disillusionment with politics generally

“NORTHERN IRELAND is like a child that is not thriving.” So said a well-respected community leader to me recently. He is surely right. So much seems to be in poor health, for so much remains seriously contested – identity, culture, territory, history, education, to name just a few issues. Public discourse is often atrociously abusive, and even the democratic processes themselves shake from time to time, even though we all know they are unlikely to collapse.

Uncomfortable Conversations is a welcome project, for clearly there is a need for such conversations to take place across a whole range of issues if good societal health is to be restored. What is not clear is whether there are, as yet, any agreed and desired outcomes for those conversations. The National Chair of Sinn Féin set out clearly the background thinking of the party to the initiative in March 2012:

“It is an unequivocal and open invitation from the Sinn Féin leadership to engage with, and listen to, civic and political unionism, loyalism, trade union movement, academia, the faith community, the police and the British state. It is not only about having the Uncomfortable Conversations but creating a public momentum that asks the question how we collectively engage with the legacy of our past and build for the future.”

This raises a number of other questions for me.

Given that both republicans and unionists are sharing power together at Stormont, is it therefore agreed that to build for the future we need to make Northern Ireland work well as an entity distinct from the Republic of Ireland?

Are we agreed that violence – from whatever source or with whatever alleged rationale – must be off and stay off the agenda permanently for the future of our people and our island?

Are we agreed that effective citizenship can be nurtured and developed within the complex identities involved in being Irish and/or British and/or Northern Irish and/or of belonging to one of the incoming communities?

Are we agreed that we need to stop looking to others to sort out our problems and apply ourselves to the need to build consensual and coherent public policy ourselves?

Can we agree that to deal adequately with the toxic legacy of our past requires a lot more than what governments, agencies, institutions, the judiciary or politicians can deliver? Clearly they can and should play a hugely important role but on their own (and even together) they cannot plumb the depths of ongoing and profound pain, distress, grief, mistrust and anger.

I would expect that the responses to each of these five questions would be an unequivocal ‘Yes’. If there is ambiguity or ambivalence about the responses, then the Uncomfortable Conversations are about managing the difficulties better rather than about dealing with them. Indeed, I would suggest that the lack of traction for the Uncomfortable Conversations project amongst many people outside the republican tradition lies partly in the widespread disillusionment with politics generally alongside a deep uncertainty about the answers to those questions.

The renewing of the call from 1916 at Easter this year to break the connection between this country and the British Empire and to establish an Irish Republic signals to unionists that there may be little interest in making Northern Ireland work well. Of course, that is not necessarily the case but the ambivalence needs to be addressed.

I write this piece not as a political or social commentator, for I am neither. I am an ordinary Presbyterian minister with some experience of living in a deeply divided part of Belfast. I am being careful not to express a political preference, for our church is an all-Ireland church, with every political loyalty included in its membership. I want good conversations very deeply, for without it the current desert of public debate will only expand, even though there are oases of wisdom and grace dotted over the landscape.

I am motivated day and daily by the call in the Old Testament for God’s people to seek the welfare of everyone around them, including those whom they saw as enemies and even oppressors.

The core principle that I long to see underpinning our Uncomfortable Conversations is what will be for the common good, rather than what will benefit my group, my party, or myself.

I see no need to contest every issue, or win every debate, or take every hill. But I do see the need for those who are uninterested or unable or take part in Uncomfortable Conversations to benefit from those conversations.

So I end where I started. What can we do to make Northern Ireland thrive? In asking that question, I readily acknowledge that it cannot but lead us into a further series of very Uncomfortable Conversations indeed.

Rev Dr Norman Hamilton – Former Moderator of the Presbyterian Church Chair, Public Affairs Council of the Presbyterian Church

Editor’s Note: Guest writers in the Uncomfortable Conversations series use their own terminology and do not always reflect the house style of An Phoblacht.