16 May 2016 Edition

We need to bring back Ireland’s native woodlands

Conifer plantations not the answer to climate change

• Ireland's native broadleaf forests have been superseded by conifer plantations

The destruction of Ireland’s forests intensified in the 1500s. Under successive British monarchs, Ireland’s forests were devastated with much of the wood used to help build up the British Empire’s navy which would eventually end in the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588

THROUGHOUT the 2016 Dáil general election campaign there was widespread criticism over the lack of coverage and discussion of environmental issues despite climate change and global warming being one of the most important issues facing the world today.

On the final televised Leaders’ Debate of on RTÉ television, only a few seconds were afforded to each party on the issue. All parties have embraced green politics to one degree or another. While the responses on TV were positive, there was criticism of the seeming very broad answers given. One pertinent point was, however, raised by Sinn Féin’s Gerry Adams when he said we “need to grow native trees”.

At just 11% of land area, this state has the lowest level of tree cover in the European Union. The state hopes to increase this to 18% by 2050 through afforestation actions by the forestry service Coillte. Currently, only about 1% of native Irish woodlands remain and the overwhelming majority of afforestation carried out by Coillte involves planting non-native conifer trees which are economically beneficial and used for producing timber. The forestry industry is now worth over €220million per year.

The destruction of Ireland’s forests intensified in the early 1500s. Under successive British monarchs, Ireland’s forests were devastated with much of the wood used to help build up the British Empire’s navy which would eventually end in the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. By the early 1600s the notorious British East India Company had moved 300 English settlers to Dundaniel in Cork, where it established a shipyard and iron ore works. There was another reason for this destruction – to deprive the native Irish resistance guerrillas, known as the Wood-Kernes, of cover for their constant ambushes and harrying attacks against crown forces.

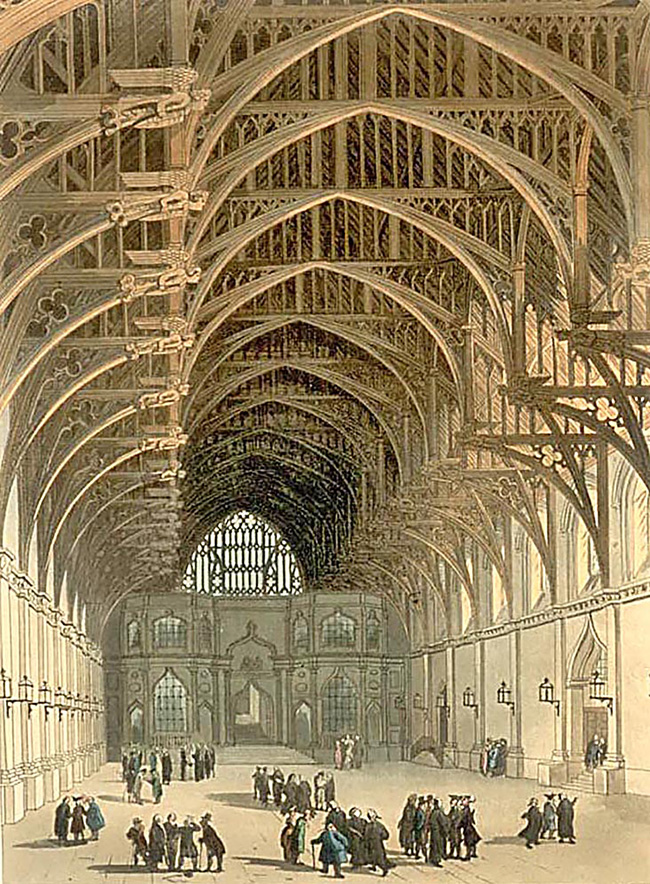

• Irish oak was used for Westminster Hall's roof

Throughout the 1600s, Ireland provided the wood needed for Britain’s insatiable appetite for timber. In 1630, Irish Oak from Shillelagh Woods in County Wicklow was selected to be used to construct the ornate roof of Westminster Hall. By 1800, Ireland’s sprawling woods and forests were all but gone – only remnants remained, dotted throughout the country in usually inaccessible and mountainous areas.

The eradication of Ireland’s forests hugely impacted the island’s wildlife. Native species like wolves, wild boars and the red squirrel became extinct (our modern red squirrels were only reintroduced in the 1800s) while native bird populations were decimated.

Across Europe, broadleaf forests made up 70% of all forests in 1750. Today they make up only 43% with the rest being conifers.

• Recent studies suggest the widespread planting of conifer forests in Europe is actually contributing to global warming

Pádraic Fogarty of the Irish Wildlife Trust says today’s reforestation campaign’s over-reliance on “non-native conifers is associated with water-pollution, loss of native wildlife and landscape impacts”.

The overwhelming majority of indigenous trees in Ireland are broadleaf. Ireland has only three native conifer trees (Scots Pine, Juniper and Yew) yet today the bulk of Ireland’s forests consist of non-native conifers.

A new study conducted by researchers at the Laboratory of Climatic Science and Environment (LCSE) at Gif-sur-Yvette in France found that, despite an increase of almost 10% of wooded area in Europe over the last 260 years, the continent’s forests have actually contributed to global warming.

How? Because the shift from native broadleaves to more economically valuable conifers like spruce and pine means less water is evaporated into the atmosphere while the dark colour of these trees reduces the amount of sunlight reflected back into the atmosphere and instead traps it – increasing temperatures.

The fact most of these forests are managed by forestry agencies such as Coillte, means that these trees are often removed for wood products and the area replanted – meaning carbon that was removed from the atmosphere and would have been stored in them is released from the leaf litter and dead wood in the soil’s carbon sinks.

Summing up the findings of the report, the LCSE team said:

“The key question now is whether it is possible to design a forest management strategy that cools the climate and, at the same time, sustains wood production and other ecosystem services.”

In Ireland, the over-reliance on planting non-native conifers needs to be reassessed, and the return of Irish woodlands needs to take priority.