7 March 2016 Edition

Manchester’s 1916 martyrs and Arthur Griffith

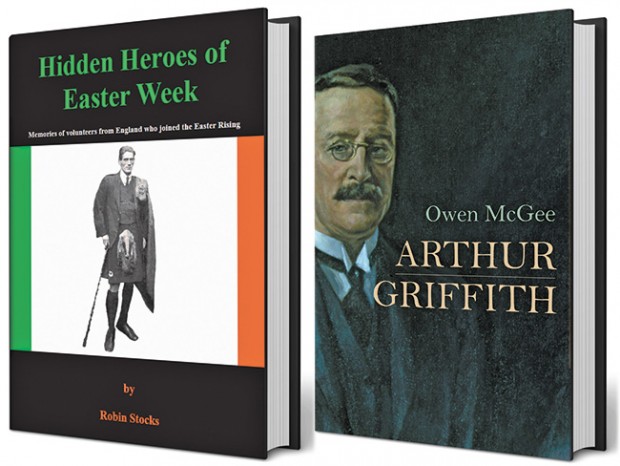

BOOK REVIEWS

Hidden Heroes of Easter Week: Memories of Volunteers from England who joined the Easter Rising

By Robin Stocks

IT WOULD BE A PITY if the excellent and very readable Hidden Heroes of Easter Week, with its original research as a self-published work, was lost in the deluge of books from commercial publishing houses on the 1916 Rising. It’s a page-turner.

Hidden Heroes is an examination of the part played in the Easter Rising by Volunteers from England and Scotland. Whilst the Tan War was mostly credited to Munster and Dublin, the Easter Rising is often seen as Dublin’s alone. As a consequence, the actions of the hundred or so Volunteers who travelled from England and Scotland have long been overlooked. This book helps to redress that balance.

The book follows the lives of two Volunteers from Manchester and a Cumann na mBan member from Dublin who subsequently married one of them. Their lives are traced from their formative years until their eventual deaths, with the main body of work devoted to Easter 1916.

This is an absolute gem, full of interesting narrative and packed with fascinating anecdotes which paint a very real picture of both ordinary life and momentous events.

The mood of the time is ably illustrated by stories such as that of the Cunard White Star Line in November 1915 refusing to carry 700 Irishmen from Liverpool to America to ensure they would be available to fulfil their ‘patriotic duty’ and join the British Army.

Fascinating pen pictures of the Rising itself emerge, Michael Collins was “aggressive . . . lacking elementary knowledge” and unpopular, according to Irish Volunteer Joe Goode.

The volume is packed with insights such as these. Wonderfully researched and beautifully written, it is one of the most enjoyable books I’ve seen for some time and really deserves to have as wide a readership as possible. Do try and obtain a copy, and you’ll be glad you did.

Hidden Heroes is available from hiddenheroesofeasterweek.wordpress.com, Amazon and Kindle.

Arthur Griffith

By Owen McGee

EVERYONE KNOWS a few facts about Arthur Griffith. He founded a political movement called Sinn Féin, he was instrumental in securing the signing and ratification of the Treaty, he was a pillar of the nascent Free State Government – and that’s probably about it. Some people may know that he was a vocal advocate of the “dual monarchy” idea along the lines of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (two separate parliaments under the auspices of one monarchy). In most other respects, he remains an enigma to the vast majority of Irish people.

This new biography shines a light on many aspects of Arthur Griffith’s life but is frustratingly reticent on others. This is basically a political and economic history as much as a biography. It is packed with fine research and detailed analysis and interpretation of the evolution of Arthur Griffith’s political views, and how he sought to exercise them.

What it is not is a personal biography of the man as an individual human being with an emotional as well as a political dimension. It is only when writing about Griffith’s travels in southern Africa, through Zanzibar and Mozambique, that his humanity really begins to show.

Arthur Griffith may well have been something of a charisma-free zone, but he is without doubt a fascinating individual.

Born into a relatively poor family in inner city Dublin, he grew up in a tenament building in Upper Dominick Street. He was largely self-educated, having left formal education at the age of 13. He was a voracious reader and keenly interested in self-improvement as well as youthful protest politics. His views were a product of these formative years which, it has to be remembered, were the 19th, not 20th, century. As the author states: “His life began in 1871, not in 1917.”

Dr McGee ably charts Griffith’s progress amongst the myriad of political, social and cultural organisations that proliferated in Irish society at this time. The slightly chaotic overlap of these groups, often with diametrically opposing agendas, explains much of the background to Griffith’s sometimes eclectic beliefs. Unusually for his time, his main contention against Britain was not one of cultural domination but economic and fiscal control purely in Britain’s interests.

The complexity of Griffith’s contribution, character and legacy is best illustrated by the fact that the author’s conclusion runs to 49 pages. This book serves to illuminate a character that is described as “representing a past that no longer seems to suit . . . and so has been necessarily airbrushed out of Irish history”. This scholarly tome firmly restores him as an important figure in the formation of the modern state.