25 September 2015

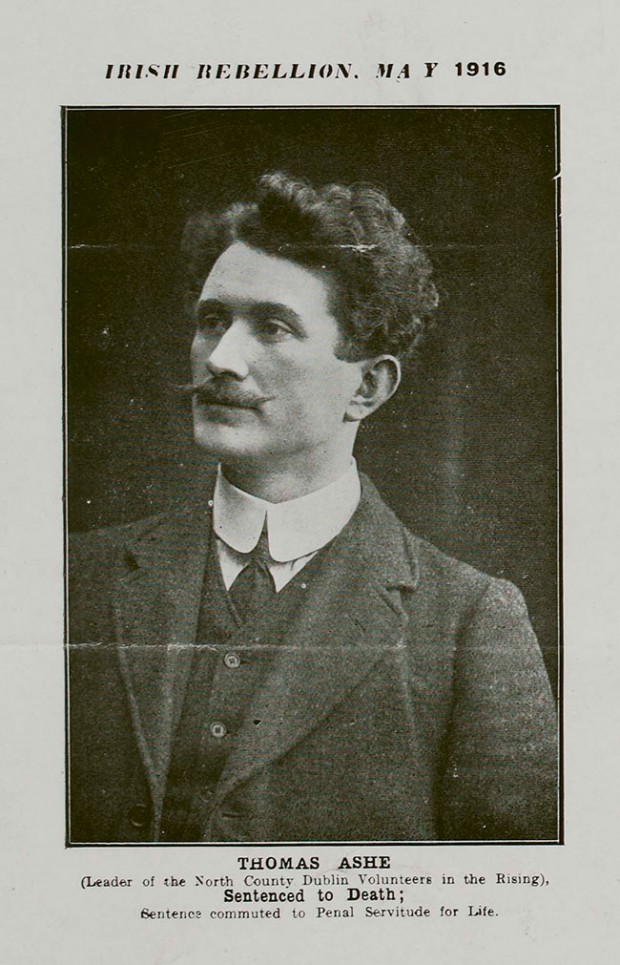

The First Hunger Striker – Thomas Ashe

BORN IN 1885 in the small village of Lispole, near Dingle, County Kerry, Thomas Ashe was educated locally. He qualified as a teacher in the De La Salle Teacher Training College in Waterford City, later taking up the position of Principal at Corduff National School in Lusk, County Dublin.

Ashe had great interest and involvement in the nationalist movement and was a member of the Irish Volunteers and Conradh na Gaeilge. Through his links with these organisations, Ashe was recruited into the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Evidence of the respect in which he was held was witnessed by the fact that he was chosen to visit America on a fundraising trip. It was during this time that he met the likes of John Devoy, Joe McGarrity and Roger Casement.

The years leading to the 1916 Rising saw Ashe take up a more prominent role and by Easter Sunday 1916 he was the Commanding Officer of the Dublin 5th Battalion of the Volunteers.

During the Rising, Ashe and his battalion of just 48 men led many successful attacks and ambushes on military barracks around the north Dublin area. This group successfully demolished the Great Northern Railway Bridge, thus disrupting access to the capital. In addition, they captured the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks at Ashbourne, County Meath. The fight to gain control lasted six hours, during which time 11 RIC men were killed and over 20 were wounded. By comparison, the Fingal Battalion lost only two men and five were wounded.

Ashe and his men captured three other police barracks with large quantities of arms and ammunition which kept their highly successful guerrilla war going.

When news of the surrender reached Thomas Ashe, he laid down his arms and was arrested, court-martialed and sentenced to death. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

He was released as part of the general amnesty in June 1917. On his release, Ashe immediately became involved once more in the independence movement. Thomas Ashe was elected President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, taking the place of the executed Pádraig Mac Piarais. He travelled the country campaigning for Sinn Féin, making speeches which the authorities deemed were “calculated to cause disaffection”.

Thomas Ashe was rearrested for sedition and incitement of the population on 15 July 1917 and sent to Mountjoy Jail. He demanded that he be given Prisoner of War status, including the right to wear his own clothes and associate with his fellow inmates. When the authorities refused his demand, Ashe and six of his fellow prisoners went on hunger strike. Ashe was put in a straitjacket and force-fed by the authorities. All requests to Ashe to end the hunger strike were refused. He was adamant in his conviction, saying: “They have branded me a criminal. Even though if I die, I die in a good cause.”

Administered by a trainee doctor, the process of feeding was often quite brutal. On the third day, Ashe collapsed shortly after the gruelling procedure. It was later discovered that the tube had pierced his lung, among other complications. He was released immediately from the prison and taken to the nearby Mater Hospital. Two days later, he died of heart and lung failure.

After lying in state at Dublin City Hall, Ashe’s cortege made its way through Dublin to Glasnevin Cemetery on 30 September 1917. It is estimated that 30,000 people lined the streets, some having travelled great distances and overcoming such obstacles as limited transport to attend.

At the graveside, Volunteers fired a volley and then Michael Collins stepped forward and made a short and revealing speech in English and Irish. His English words were: “Nothing additional remains to be said. That volley which we have just heard is the only speech which it is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian,” leaving the Irish population in no doubt what was needed to gain independence.

● The graveside salute to Thomas Ashe

The death of Thomas Ashe had a striking effect on the attitude of the Irish people. The Rising of 1916 now became the focal point of passion by reason of the sacrifices of the signatories of the Proclamation. The brutal manner of the death of Ashe, superimposed upon the summary executions of the 1916 leaders and other atrocities committed by the crown forces, galvanised the nation. Committees sprang up all over the country to pay tribute to the memory of this brave man and indirectly fuelled the fire of Irish independence.

On 25 September 1917, Thomas Ashe died as a result of force-feeding.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures