1 December 2014 Edition

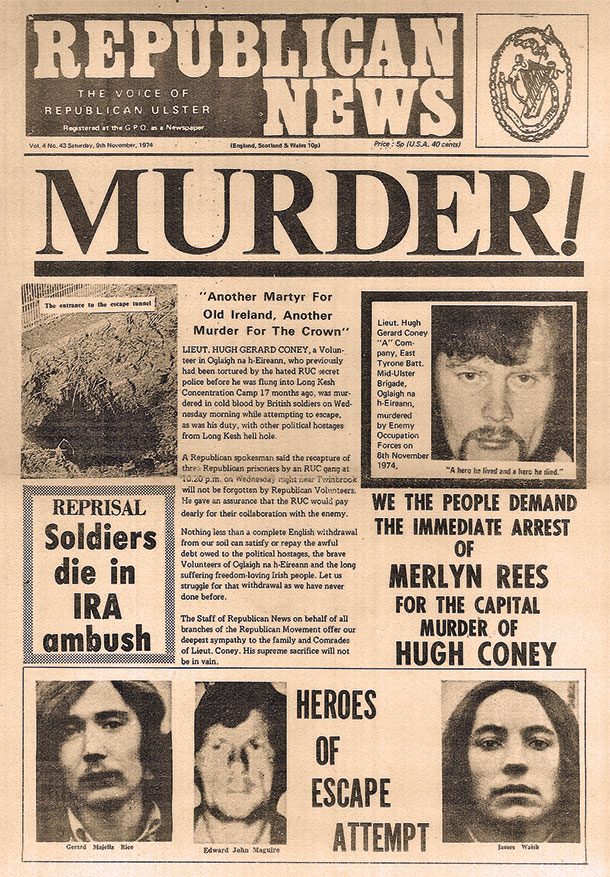

The killing of Hugh Coney

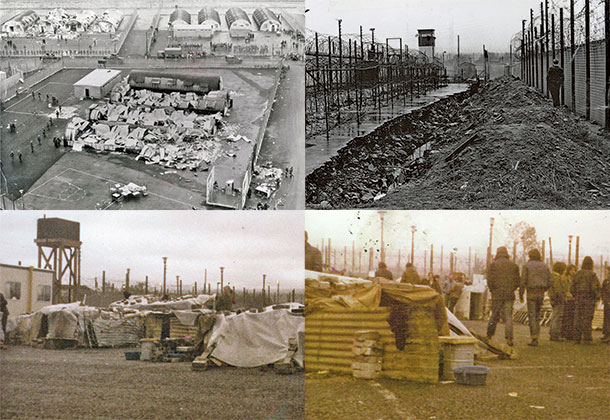

Long Kesh 1974: in the aftermath of the burning of the prison camp

‘There was a shout of ‘There’s someone in the field’ and then I heard the two shots’ ... British soldiers allowed their guard dogs to bite and snap at Hugh’s defenceless body

IRA VOLUNTEER HUGH CONEY was shot dead by a British soldier after the republican POW had tunneled his way out of Long Kesh in 1974 and attempted to escape across fields.

The circumstances of his killing can sometimes be overshadowed by what were truly exceptional events in the aftermath of the burning of the prison camp by the republican prisoners incarcerated there.

This is partly due to the publicity surrounding ‘The Burning of the Camp’ itself and the excessive brutality meted out to the prisoners by the British Army and prison warders as they exacted revenge on the POWs.

With the British authorities refusing to release information about the conditions of the prisoners, especially those injured and moved to hospital and isolated, the families of the POWs, sentenced and interned, and their representatives were struggling to get information.

Added to this, rumours were starting to circulate, increasing the worries of people on the outside, that the British Army had deployed a deadly new gas, CR gas, as they pulled out all the stops to quell the mutiny.

In Armagh women’s prison, republican POWs under the leadership of Eileen Hickey captured the prison governor prisoner in an act of solidarity with their male comrades.

And republican remand prisoners took over ‘A’ Wing in Crumlin Road Jail while sentenced men in Magilligan in County Derry also torched their camp.

•The aftermath of the burning of Long Kesh

Yet, 40 years after ‘The Burning of Long Kesh’, carried out over the night of 15 October, leading into 16 October (when the serious fighting between the captured IRA prisoners and the British Army took place) the details surrounding the killing of Hugh Coney, just weeks after the burning, reveal another chapter in a story of bravery and commitment involving Irish republican POWs.

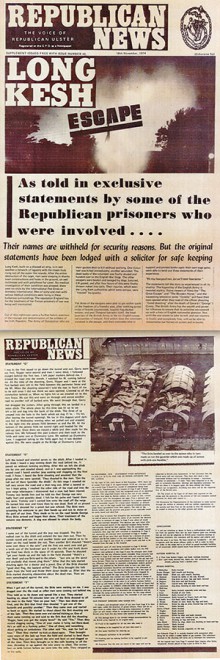

Sinn Féin MLA Fra McCann, who at that time was in his second spell of internment and who was part of an escape attempt that, had it gone to plan, would have seen hundreds of republicans break free “and rejoin the struggle” spoke to An Phoblacht about that life or death struggle in Long Kesh.

McCann, from the Lower Falls in west Belfast, was first interned in February 1972 and spent the first 30 days of his incarceration on the prison ship Maidstone before being moved to Long Kesh.

He was released in May, only to be re-arrested in November of that year. He was one of the last internees to be released when he was set free on 23 December 1975 when the British ended internment as a prelude to the implementation of it’s criminalisation policy.

As the internees were being released, the British Government was building the now infamous H-Blocks.

After the prisoners torched Long Kesh, destroying prison administration buildings as well all their own accommodation, they were left having to survive as best they could.

Using the corrugated iron sheets from their hut roofs. they built makeshift shelters.

In time-honoured fashion, the situation gave rise to what Fra describes as “the best opportunity and conditions for digging an escape tunnel that we’d ever had”.

The Officer Commanding (OC) of the internees at the time was Lower Falls man George Gillen, and he sent the order out: “Prepare for escape.”

As tunneling produced tons of soil, hiding it always proved a problem “but with the camp being like a moonscape we could get rid of the soil easily”. Nor could the ‘screws’ – the prison officers – keep track of the prisoners’ movements as the numbers in Cage 5, where the tunnel was being dug, had doubled.

Working 24 hours a day, the POWs beavered away, moving tons of soil, mud and dirt out of a tunnel that was prone to flooding and collapse due to the conditions of the terrain at Long Kesh.

Fra singled out ‘Big Ned’ Maguire for the colossal amount of work he carried out in the tunnel. After a cave-in on one occasion, Ned took the weight of the collapsed section on his back to give other prisoners the space and time to insert new props and repair the damage.

“He had amazing brute strength,” says Fra.

Again the corrugated iron from the huts came in useful as hoardings or as flooring at “the bottleneck”, a part of the tunnel that flooded constantly.

The longer the tunnel got, the more difficult it became for the tunnelers to see. The Cage OC told the screws that the prisoners needed electric cable and lighting to illuminate the Cage for reading. Amazingly, they gave it to him.

One of the internees, an electrician, wired up a lighting system in the tunnel.

After a lot of energy had been expended, the tunnelers realised they were doubling back on themselves so, in an incredible feat of engineering and ingenuity, one of the prisoners ‘invented’ a makeshift device that enabled the teams to dig in the direction they needed to go in.

As there was obvious communication with the republican leadership on the outside, keeping them informed of the situation in the camp and the progress of the tunnel, it was agreed that a number of handpicked IRA Volunteers were to be given priority on the escape.

Coalisland man Hugh Coney was one of those Volunteers so he was moved into Cage 5 prior to the final push.

Fra recalls:

“There was a number of false starts but on the night of 5 November we got the go-ahead and the escapees went out in squads with the first squad made up of, among others, ‘Big Ned’ Maguire and Hugh Coney.”

Fra McCann was in the second group to go and he recalls how the tunnel had come up just short of an internal ‘patrol road’ used by British Army mobile patrols.

“I made my way over the open ground and crossed the ‘patrol road’. There was an open ditch on the other side and I rolled into it. This was as far as the first squad had got due to obstacles and fences. They had to cut through on account of the tunnel stopping short of the main perimeter fence.

“I was lying in the ditch as the men in the lead group cut the fence separating the British Ministry of Defence land and a farmer’s field. Once through that we were out.”

It was at this point that Fra heard shouting.

“As a Brit patrol drove along the ‘patrol road’ they spotted one of the escapees. There was a shout of ‘There’s someone in the field’ and then I heard the two shots.

“One of the rounds hit Brendan Shannon, grazing him on the side; the other hit High Coney, killing him more or less instantly.”

In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, the British soldiers ordered the prisoners to lie on the ground spreadeagled. As reinforcements arrived with dogs, they set about beating their captives and setting the guard dogs on them.

The fatally-injured Hugh Coney was left lying there as the British soldiers refused to immediately summon medical assistance. They allowed their dogs to bite and snap at Hugh’s defenceless body.

One British soldier asked: “Who certified that cunt dead?”

Another responded: “Nobody, officially, but if we leave him for half an hour he’ll die with pneumonia anyway.”

Of the 30 or so prisoners to make it out of the tunnel, all except three were recaptured straightaway and all were subjected to beatings by the captors as well as having dogs set on them.

The three who made good their escape – ‘Big Ned’ Maguire, Gerard Rice and Gerard Walsh – initially dug themselves into the bank of a stream where they hid for 24 hours before attempting to make their way back to Belfast.

Amazingly, despite the huge security dragnet stretching almost ten miles, the trio got to the outskirts of west Belfast, getting to within a mile of Twinbrook before they were recaptured.

The threat they were under was immense as, according to Fra McCann, the notorious SAS had been deployed to search for them.

Loyalist gangs were also out ‘patrolling’ the area in the hunt for the three escapees.

“This was a major operation,” McCann emphasizes. “This escape had the potential to get dozens, maybe hundreds, of experienced IRA Volunteers back onto the streets, especially at a time when the nature of the struggle was changing.

“And after the burning of Long Kesh, for the republican people of the North to wake up to the news of a mass escape it would have a massive morale boost. Sadly, it wasn’t to be and not only did we have to wait for ‘The Great Escape’, instead we lost a dedicated and committed Volunteer in Hugh Coney.”

• The funeral of Volunteer Hugh Coney

• Protests following the death of Hugh Coney