20 April 2014

The Rising outside Dublin

This feature first appeared in An Phoblacht/Republican News on March 28th 1991 to mark the 75th anniversary of the Easter Rising

WITHOUT DOUBT, had a large-scale rising taken place throughout the country, albeit based on the confused and conflicting plans prepared by the IRB’s Military Council, the story of Easter Week 1916 might well have been very different.

A number of factors combined to frustrate attempts for a successful rising in large areas of the country outside Dublin.

These included the badly prepared plans for a rising in the country as a whole; the arrest and deportation of a number of provincial leaders prior to the rising, particularly in Munster; the divisions that existed and the secrecy among the members of the Irish Volunteer Executive and the IRB’s Military Council; Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order; the lack of proper communications with the commandants in the provinces; and lastly the failure of the arms ship the Aud and the expected arrival of German support.

That plans existed for a rising outside Dublin there is no doubt but how elaborate and effective these were is open to much speculation.

Liam Mellows

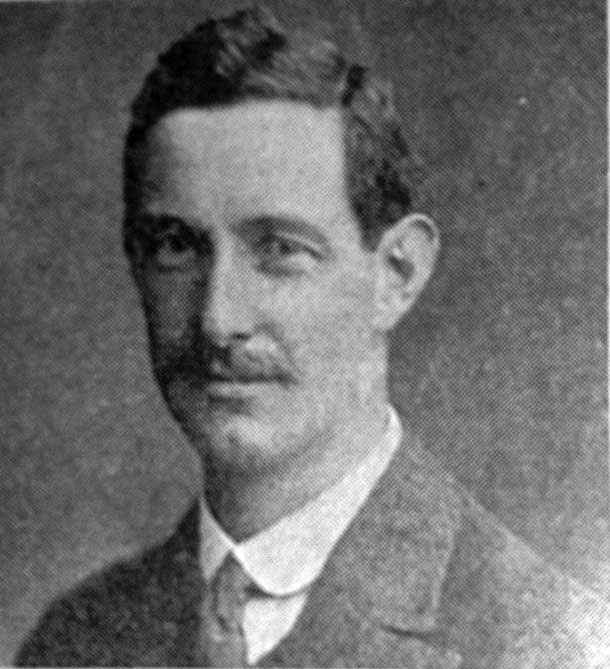

Pádraig Pearse’s declaration that there were in existence “arrangements for a simultaneous rising of the whole country, with a combined plan as sound as the Dublin plan” is supported by Liam Mellows. He confirmed this following his return to Ireland after his escape from England, to where he had been deported. He had been taken into Pearse’s confidence and left St Enda’s on the Thursday before Easter to take command of the Volunteer forces in Galway.

The overall plan for the Rising in the country (especially in the south-west and west of Ireland) is generally believed to have been similar to the plan for the rebellion in Dublin – which involved the seizing of defensive positions, and the setting up of garrisons and outposts in strategic public buildings in the capital – though no conclusive evidence of this plan exists.

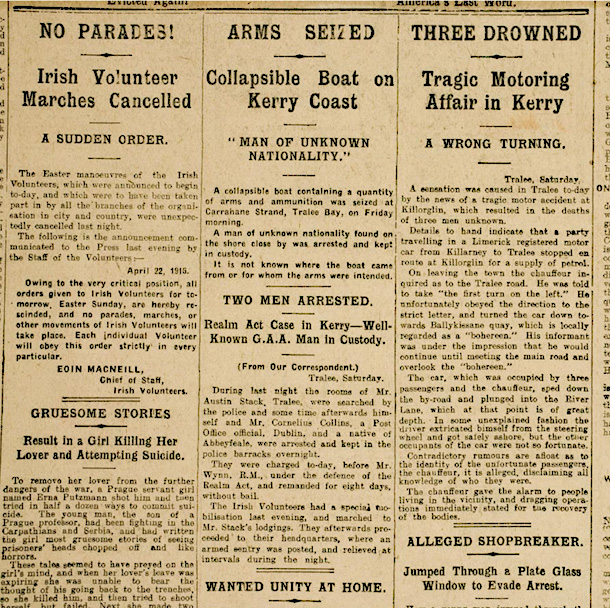

If the Dublin plan was indeed a blueprint for use in other areas, there is little evidence that it had been explained to the officers in the provinces. And the lateness of its announcement (a notice in the Irish Volunteer of Saturday, April, 22nd 1916) would have left little time for working out details with regard to the selecting, seizing, provisioning, fortifying and defending of specific buildings in cities and towns on the lines of the Dublin plan, which was being perfected for more than a year.

The success of the country-wide plan, however, was very much dependent on the successful landing of the arms and ammunition from the Aud and the expected arrival of 5,000 German reinforcements.

On Thursday, April 20th 1916, Eoin MacNeill (Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers), on learning of the proposed Rising for the following Sunday was persuaded not to cancel the Volunteer manoeuvres for Easter Sunday, having been reassured that German aid in the form of arms and ammunition would successfully arrive within days. But within hours the first serious blow to a countrywide Rising occurred.

That night, five Volunteers chosen to take part in establishing a transmitter to send messages to British ships to divert them from the Kerry coast set out for Ballyard, near Tralee in County Kerry. In the early hours of the following morning, three of these Volunteers (Charles Monaghan, Donal Sheehan and Con Keating) were drowned in the River Laune after driving off the Ballykissane pier due to dense fog.

Arrests in Kerry

Later that morning, an event which was vital to the success of the Rising outside Dublin occurred.

The German submarine, U19 (carrying Roger Casement, Captain Robert Monteith and Daniel J. Bailey) reached the planned rendezvous point with the German arms ship, the Aud. Unaware of the change in plan to land the arms at Fenit, in County Kerry, on Easter Sunday instead of Good Friday, the Aud anchored off Tralee Bay while Casement, Monteith and Bailey landed in a dinghy from the submarine at Banna Strand at 1.30pm.

Hours after landing, Casement was arrested at McKenna’s Fort, Banna Strand. Monteith and Bailey travelled to Tralee, where Bailey was arrested. Monteith, however, made his way to Cork.

That day, the Kerry Volunteers suffered another fatal blow with the arrest of Austin Stack, the commandant of Kerry.

At 9.28am the following day, rather than have his cargo of arms fall into the hands of the British, Captain Karl Spindler and his crew scuttled the Aud off the Kerry coast.

On learning of the scuttling, MacNeill immediately dispatched messages throughout the country cancelling the Easter manoeuvres for all Volunteers, throwing officers and Volunteers not only in Dublin but also in the country into confusion and dashing all hopes of a rising outside Dublin.

In anticipation of Volunteer leaders obstructing the Rising, and fully aware that MacNeill and Bulmer Hobson were opposed to it, the Military Council had instructed IRB members to disregard all orders except those emanating from known IRB men. They appear to have been fully confident that they could overcome opposition from the Volunteer Executive and that ‘their men’ would be capable of committing the whole Volunteer organisation to a rising.

The evidence of any detailed plans for a rising in most areas in the country is slight, except for vague general instructions to the Limerick, Clare and Galway brigades about “holding the line of the Shannon” and “relieving the pressure on Dublin”. Had this co-ordinated plan for using the line of the Shannon and for trying to prevent British forces from penetrating into Connaught been put into operation, it might have prolonged the Rising for a considerable length of time and would certainly have given the enemy a more formidable task than the reduction of Dublin alone gave them. Like the Dublin plan, it was to have been a defensive one but it is difficult to believe that the handful of Volunteers available, even with the addition of German armaments, would have successfully captured and held large cities and towns like Limerick and Athlone.

The Military Council did, however, take steps to organise Volunteer movements in the southwestern and western counties which was to be the main centre of action outside Dublin. Following the landing of the arms from Germany in Kerry at Easter, the commanding officers of Cork, Kerry, limerick and Galway were to occupy positions which would enable, them to cover the arms landing, and ensure the protection and distribution of the arms.

Plans changed

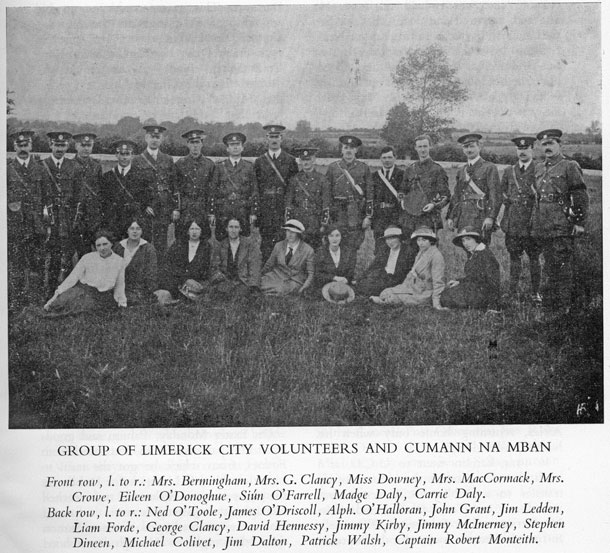

On the eve of the Rising, Michael Calivet, the commandant of Limerick, who was completing his plans for holding the line of the Shannon from Limerick to Killaloe, County Clare, and capturing Limerick City, had his instructions altered by the Military Council.

On Tuesday of Easter Week he was put in charge of a vast area covering several counties by Pearse, who directed that (following the landing of the arms in Kerry and the supervision of the collection and distribution of arms for his own men and for the Galway Volunteers) he was to attack police and military barracks and cut telegraph, telephone and rail communications.

When all this had been accomplished and the position in Limerick was under his control, they were to march eastwards and relieve Dublin in what was a major shift away from the previous defensive plans. It is difficult to understand the reasons for the sudden change of plan which would have resulted in these poorly-trained Limerick Volunteers engaging in an offensive role while no such task had been allocated to the Dublin Volunteers who had been preparing for a rising in the city for more than a year.

The loss of the Aud on Saturday, April 22nd 1916, threw these plans into total confusion and MacNeill’s countermanding order dealt a fatal blow to the hopes for a successful rising not only in the south and west but throughout the country.

Calivet, believing that the Rising should now be postponed and having received no new instructions from Pearse, cancelled all arrangements for the Easter Sunday mobilisation of Volunteers. At 2pm on Easter Monday, he received a communication from Pearse – having earlier received a message from him saying that “everything is off for the present” – announcing that the Dublin Brigade was going into action at noon that day and the instructions to Calivet were “carry out your orders”.

Chaotic situation

The situation in the southern counties and in Limerick was chaotic.

These orders were now no longer relevant following the loss of the Aud. The police and military in the south-west were on full alert and heavily reinforced. For the Volunteers, having being demobilised due to MacNeill’s ‘countermanding order, it would have been impractical in the circumstances to go on the offensive. It is not surprising, therefore, that in such a confused atmosphere a rising did not happen in Limerick.

In other counties which were to have been involved in holding of the line of the Shannon, the situation was utterly confused following MacNeill’s countermanding order. Nevertheless, the Volunteers were active in several counties.

In Kerry, the capture of Stack and local leaders who were planning to rescue Casement left the 300 Volunteers leaderless with none of them knowing the plans for the Rising or what to do. Having waited many hours for news of events, they eventually returned to their homes.

Pierce McCann

Pierce McCann, O/C of the Tipperary Volunteers, having received the countermanding order, disbanded his men. However, McCann agreed with two local Tipperary IRB men, Seán Treacy (later killed in action during the Tan War) and Eamonn O’Dwyer that Tipperary Volunteers would go into action if the Cork and Limerick men would co-operate, but though contact was made with these counties, no action ensued.

In Leitrim, Cavan and Westmeath, counties which were to have been involved in, the plan to hold the line of the Shannon attempts were made to rally the Volunteers but without success.

Defensive action only

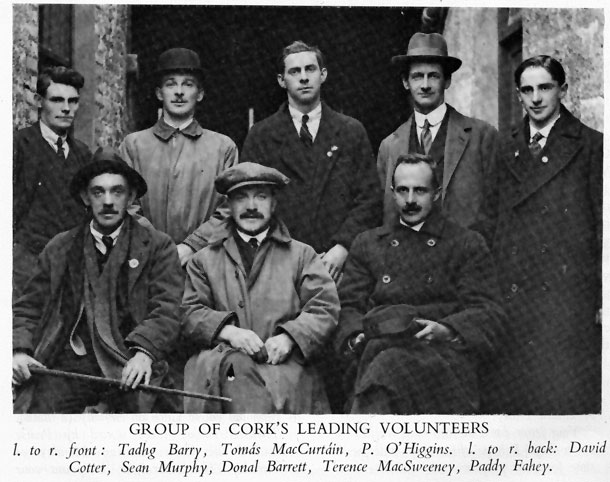

As Brigade Commandant of Cork, Tomás Mac Curtain mobilised the entire Volunteer movement in Cork, numbering over 1,000 men, and issued orders for them to assemble at Crookstown.

On learning of MacNeill’s order on Easter Sunday, April 23rd 1916, he decided to avoid further confusion and allowed units to proceed as arranged to Crookstown, where exercises took place. In the afternoon, Mac Curtain, mistakenly believing that the cancellation of manoeuvres from Dublin was backed by the Military Council, cancelled manoeuvres himself and directed all Volunteers to return to their areas.

Having set up headquarters in the Volunteer Hall in Sheares Street, he made a decision (one he did not take lightly) that the Volunteers, who were poorly armed, would act only in a defensive capacity.

During the week of fighting in Dublin, Bishop Daniel Coholan and the Lord Mayor of Cork, T.C. Butterfield, arranged a compromise with Captain Dickie on the British side stipulating that no Volunteer arrests would be made in Cork provided the local Volunteers surrendered their arms. Guarantees made on the British side were not honoured and Mac Curtain and ten other Volunteers were arrested on May 2nd.

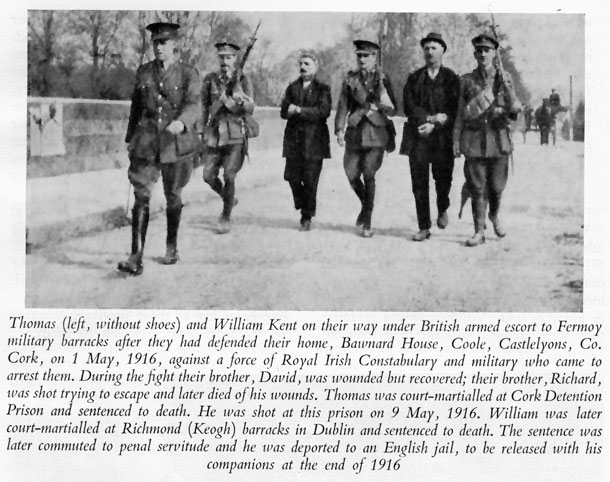

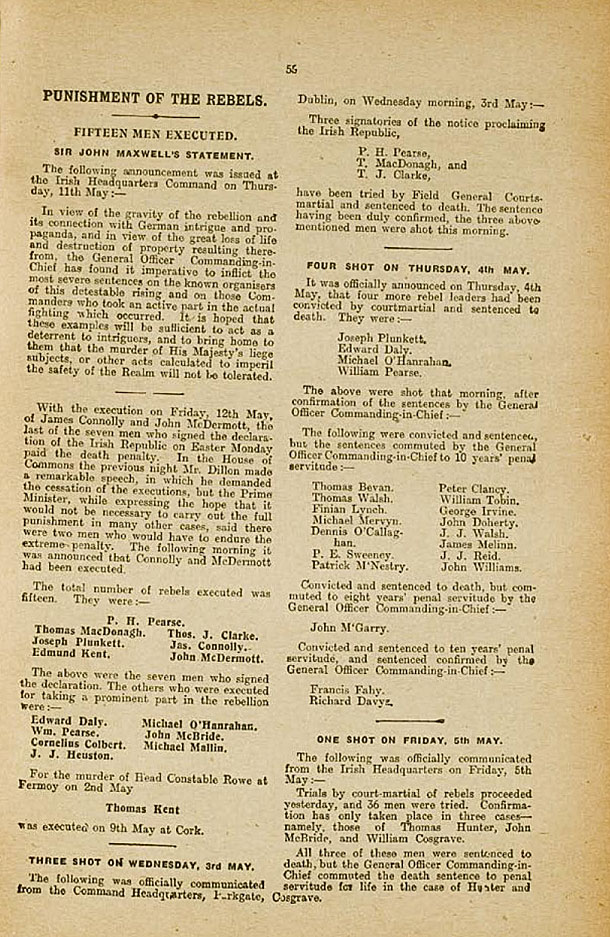

The only fighting that occurred in Cork took place the previous day, during a raid on the Kent home at Bawnard in Castlelyons, near Fermoy. During the defence of their home against British military and police, Richard Kent was killed. One brother, David, severely wounded, was sentenced to death, but the sentence was later commuted to penal servitude. Another brother, Thomas, was court-martialed, sentenced to death and executed on May 9th.

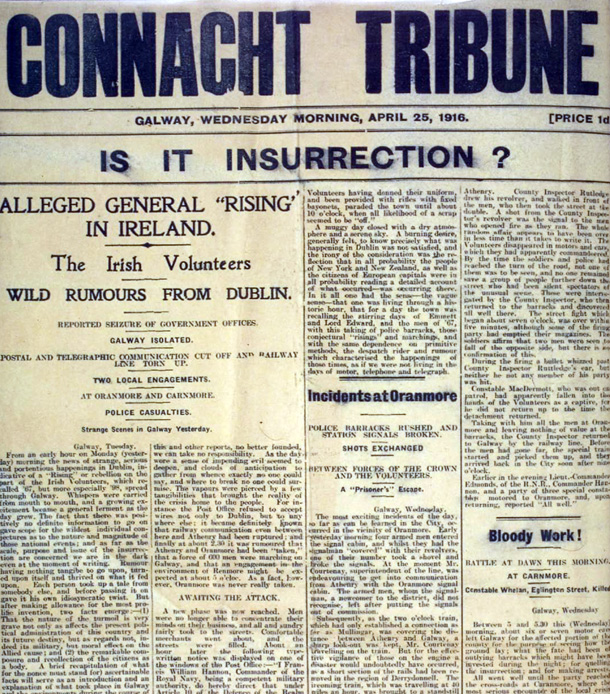

In County Galway, nearly a thousand Volunteers rallied to the standard raised by Liam Mellows. Having captured the police barracks at Oranmore and occupied Athenry, they were reluctantly forced to disband when they realised their position was hopeless, Mellows, however, refused to surrender and eventually made his way to America.

Volunteers from Belfast, Derry and Tyrone were to have arrived in Galway to co-operate with Mellows in the original plan of holding the line of the Shannon. Men from Belfast went as far as Coalisland, County Tyrone, on Easter Saturday, April 22nd, with two days’ rations but the confusion and uncertainty which they met resulted in their return home.

In military formation, Volunteers left Dundalk and marched to Ardee. Roadblocks were set up and RIC prisoners taken. The men then marched back to Castlebellingham, where they took over the RIC barracks and dispatches which had arrived from Dublin to Dundalk.

While the Louthmen tramped miles under the command of Dan Hannigan, trying to link up with the other groups and ultimately missing the Fingal (north County Dublin/Meath) group led by Thomas Ashe, which did turn out, one of their number, Seán MacEntee, succeeded in reaching the GPO before the surrender.

Ashbourne victory

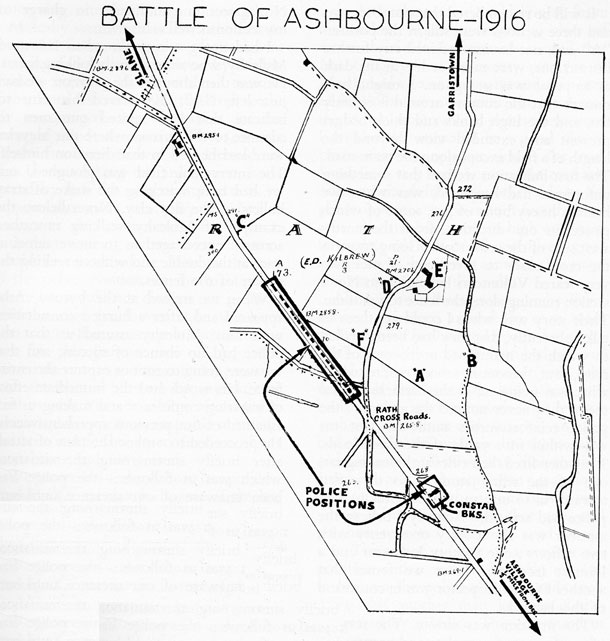

About 50 Volunteers, the Fingal Battalion, under the Command of Ashe, over-ran north County Dublin, capturing police barracks and taking nearly a hundred prisoners.

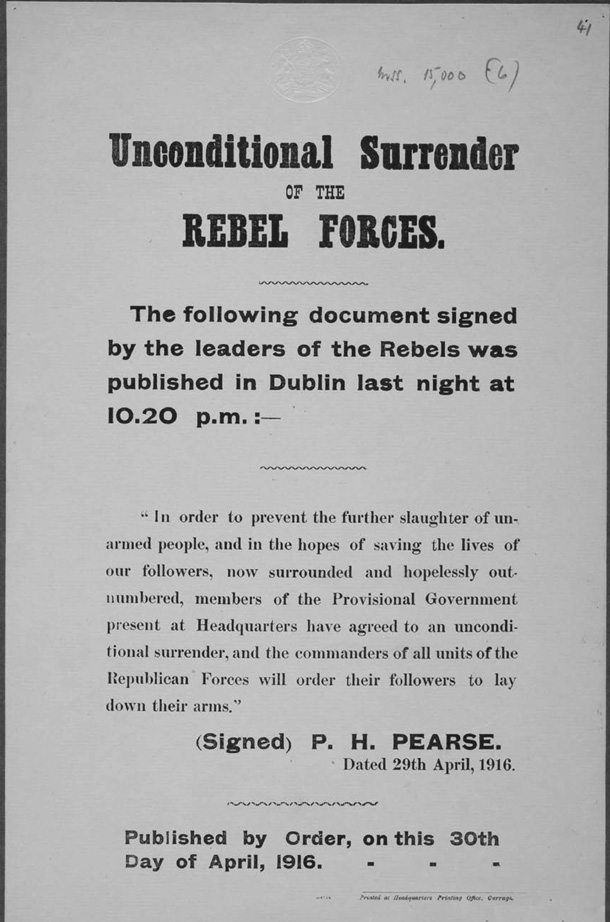

Their greatest achievement was a striking victory over superior forces at Ashbourne, County Meath, on Friday, April 28th. Like most of the men who had risen, Ashe and his comrades were reluctant to surrender and only did so following a meeting between one of his men, Richard Mulcahy, and Pearse in Arbour Hill Military Prison.

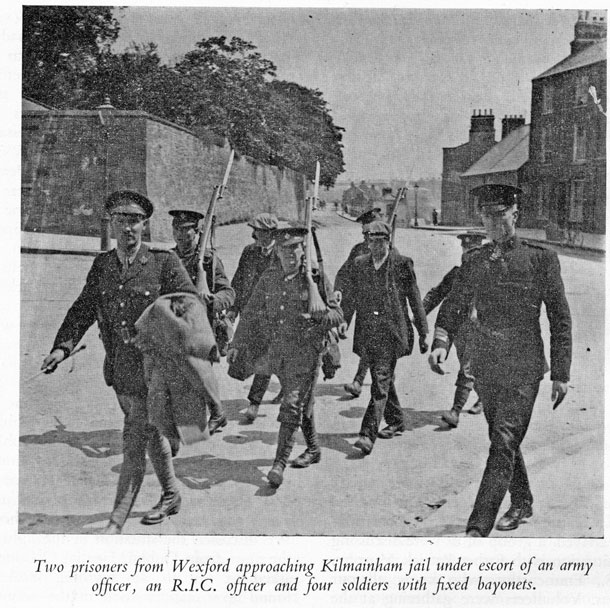

In County Wexford, Volunteers were disbanded following MacNeill’s countermanding order but there the news of the Rising in Dublin had the effect which Pearse and the other leaders had hoped for – it brought out some of the determined Volunteers led by Seamus Doyle and Seán Etchingham.

On Thursday, April 21st, the insurgents occupied the town of Enniscorthy, established headquarters and controlled the town. Another party occupied Vinegar Hill. The police barricaded themselves in their barracks and remained there until relieved. Fighting had barely commenced when news came of the surrender in Dublin and a truce was called.

Doyle and Etchingham, the Wexford leaders, were allowed to visit Pearse in Kilmainham Jail and he confirmed the surrender. “Hide your arms,” he told them. “You’ll need them again.”

Gallant efforts

Gallant though the efforts of officers and Volunteers in north County Dublin, Cork, Galway and Wexford were during Easter Week 1916, and the willingness of those in other counties to enter the fight in the circumstances that existed at the time, the Rising in the country was doomed to failure from the very beginning.

Despite the loss of the Aud and MacNeill’s countermanding order, adequate communications between the IRB Military Council and the provinces was lacking and this must be reckoned as an important factor in the collapse of such plans that did exist for a rising in the provinces.

But perhaps the most important factor in the failure of the plan for a country rising, however, was the evident non-existence of the control claimed to have been wielded by the IRB over the Volunteers. Apart from the very general secret instructions issued by Pearse to some of the IRB Volunteer officers early in 1916 (which were not understood by even all the senior commanding officers to be definite plans for a rising), IRB officers in the Volunteers, and indeed the members of the Supreme Council itself, knew practically none of the secrets of this organisation. The ordinary rank and file members of the IRB appear to have been kept completely in the dark regarding the Rising.

Considering the fact that the Dublin plans, the garrisons and outposts held by the Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army and supported by members of Fianna Éireann and Cumann na mBan held out against the full strength of the British Army for one week, it is quite conceivable that a general rising throughout the country could have lasted for a much longer period.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures