2 February 2014 Edition

Facing down the apartheid regime

• Carol Jordaan with Gerry Kelly MLA and her partner Seán Lynch MLA at a Friends of Sinn Féin event in London

She arrived at school to find that the police and the army had occupied it. ‘We immediately began singing freedom songs. They gave us three minutes to disperse; we refused and they opened fire. I still remember the screams, the noise of gunfire, and smell of tear gas.’

From ANC activist in Cape Town to nurse in Lisnaskea, County Fermanagh – CAROL DENISE JORDAAN talks to LEANNE MAGUIRE

CAPE TOWN, the travel book Rough Guides says, “is Southern Africa’s most beautiful, most romantic and most visited city. Its physical setting is extraordinary.” Carol Denise Jordaan didn’t get to ‘visit’ her own city centre until she was in her late teens because she was ‘the wrong colour’ in apartheid South Africa – she wasn’t white.

Carol was born on the outskirts of Cape Town in a very poor shanty town area. Carol’s father died when she was six years old, leaving her mother to raise a family of ten children. To survive, her mother worked as a domestic servant for a white family in a rich area. These are Carol’s earliest memories – that they were second-class citizens, a servant class.

The white supremacist South African Government had a policy of total separation of the races, what become widely known as apartheid. Black people not only lived in separate areas but had to sit only in certain seats on buses and trains, use separate waiting areas at stations, different toilets, shops, schools and even park benches.

Carol’s mother used to bring her children to the stunning Cape Town beaches on Sundays in the summer, having to pass miles of beautiful beaches with prominent signs declaring “Whites Only” before arriving at the designated “Non-Whites” beach. The law stated that breaching any of these rules would result in prosecution and imprisonment. It was strictly enforced.

“I’d never seen the centre of my city, one of the most beautiful cities in the world, until my late teens,” Carol tells me with a sadness that is still obviously with her. “It was a no-go area for my colour unless you had a special permit to work there.”

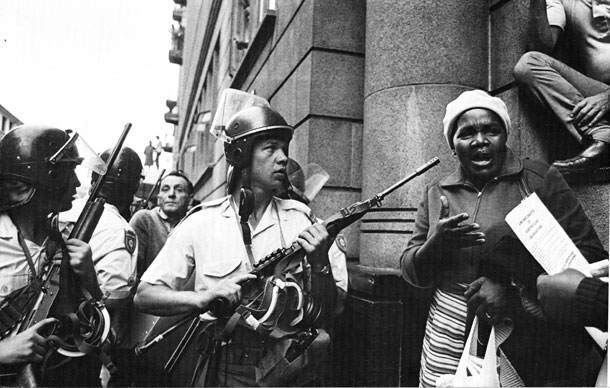

In the late 1990s, the apartheid government brought in a second-rate education system for ‘coloured’ children. Youths began protesting and rioting in Johannesburg. Demonstrations later spread to Carol’s own district of Cape Town, where the organising of youth rallies had already begun. One day she arrived at school to find that the police and the army had occupied it.

“We immediately began singing freedom songs – singing and dancing is a form of protest in our country. They gave us three minutes to disperse; we refused and they opened fire. I still remember the screams, the noise of gunfire, and smell of tear gas.

“I ran for safety, finally running into a nearby house. The woman of the house told me to quickly take off my school uniform and she gave me her own daughter’s clothes. Soldiers burst into the house and roared: “Where is that kaffir?” The woman replied: “This is my daughter. I did not send her to school today because of what was happening.” I was so grateful.

“Later, as I was making my way home, I witnessed a young boy lying dead and others been taken away in ambulances. It must be remembered that over 1,000 children and teenagers were killed across South Africa as they protested against the new education system.”

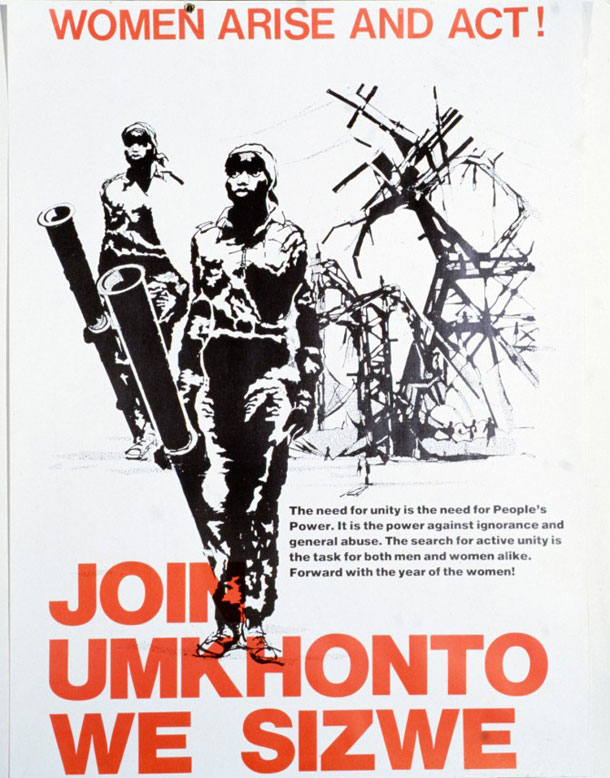

At the age of 18, Carol and some comrades established a youth movement in their district. Carol became the local movement’s first secretary and at the same time she and her sister joined the African National Congress. Some joined the military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (‘Spear of the Nation’, also known as ‘MK’).

Carol’s sister later went to train with MK while Carol neared the end of her studies in nursing and to support their mother.

“Those of us who stayed were to continue to keep the struggle alive through protests, mobilisations and low-level sabotage.

“I remember we used to commandeer food lorries and distribute the food to the poor of the area. My only role in the military campaign later was to give medical assistance to wounded MK soldiers who could not attend hospital because they would be arrested. Later this involved visiting makeshift hospitals as the struggle intensified.”

Police soon became aware of their activities and one morning the door of Carol’s family home was kicked in with the shout of “Where are those two bastards?”

Carol recalls how they brushed past her mother and burst into her bedroom, “ripping the blankets from me”.

“My mother pleaded with them that I was only a student. They left after telling my mother that two of her daughters were up to their necks in subversive activity.

“That same morning I told my mother the truth. Although concerned, she stood by us to the end. This was the same day I was beginning a new placement in one of the big city hospitals. Apartheid had also invaded hospitals. I had to enter via a ‘Coloured Entrance’ and there were white wards for white patients and vice versa.

“On one particular occasion I was bringing blood samples to the laboratory. The lift stopped at a floor, the doors opened and a white nurse was waiting. She wouldn’t get in the lift because I was there. I stood my ground. I thought to myself: I’m now a proud member of the ANC – there are things that I will not do; vacating a lift for someone else, regardless of their colour, was one of them.”

• Carol's mother Nellie worked as a domestic servant for a white family

Nelson Mandela was one of the big influences for many people she recalls, as we talk in the week after Madiba’s funeral.

“His very name was enough to inspire people to struggle and one could say he was a guiding light. I remember the day he was released. I was heavily pregnant with my first child but I made my way with thousands of others to the centre of Cape Town to await his arrival that night. Although he did arrive three hours late, his address to the people of South Africa and particularly the ANC still lives with me. He thanked us for continuing the struggle while he was in prison. I was so proud. That day I knew that freedom was on our doorstep.

“The more obvious aspects of apartheid collapsed overnight. We could walk and go where we liked.”

Other people who had a significant influence included Winnie Mandela.

“She was seen as ‘The Mother of the Nation’ when Nelson was in prison. She particularly inspired women to struggle. There were very few white people involved in the struggle in our district as only coloured people lived there. I did meet ‘white liberals’, as they were known, afterwards. I once attended a rally addressed by Joe Slovo, or ‘Red Socks’ as he was known because he was a leading communist,” Carol chuckles. “He was one of the leadership and admired by us for his sacrifice.”

At the age of 25, in April 1994, Carol witnessed another remarkable day that stays with her – South Africa’s first democratic elections. Carol and her mother, now in her 60s, attended the polling station with great pride. Carol remembers:

“There were tears in my mother’s eyes as she cast her vote. She whispered to me on the way out of the polling station: ‘I am proud of you both!’”

Carol’s activism in the ANC continued for many years and in 2004 she became the area campaign manager for Thabo Mbeki, who followed Nelson Mandela as President of South Africa. Soon afterwards, Carol left South Africa to experience nursing in other parts of the world.

“I had three choices: Dubai, London or . . . Lisnaskea! I arrived in Lisnaskea in July 2004 and I could not believe the British flag was hanging from every lamp-post. The following week they were replaced by green and white flags. I quickly learned that this part of Ireland was disputed and that the Fermanagh GAA team had reached the latter stages of the All-Ireland finals.

“It was only a number of years later that I learnt of the similar experiences and histories of our countries. I read Alex Maskey’s book, Man and Mayor, about being the first Sinn Féin Mayor of Belfast, and I realised that the nationalist people were treated as second-class citizens also.

“I could not believe the close relationship between the leaderships of both of our struggles. Republicans could talk in depth on the African struggle and its leaders. I know Madiba supported the Irish Peace Process. When he died I must admit tears came to my eyes. It was an end of an era for me and my country. We would not have had a peaceful transition in South Africa but for Madiba. He set us free from apartheid. I hung the flag from the house for a week after his passing and I am and will always remain a proud South African.”