12 January 2014 Edition

Glasnevin – Ireland’s Necropolis

A look at the fascinating history of the last resting place of 1.5million souls

• Shane MacThomáis, lead historian and curator of Glasnevin Cemetery Museum

Prior to the establishment of Glasnevin Cemetery, Irish Catholics had no cemeteries in which to bury their dead

OPENED in 1832 following years of campaigning by Daniel O’Connell, Glasnevin Cemetery is the largest non-denominational cemetery in Ireland. Within its walls and watchtowers (originally erected to deter bodysnatchers) are the graves of over 1.5million people and an estimated 200,000 monuments and headstones.

In 2010, a new museum opened its doors, providing exhibitions, walking tours and allowing people to trace their own family history. It has quickly become one of Ireland’s top historical and tourist attractions.

MARK MOLONEY met Glasnevin Cemetery Museum Lead Historian Shane MacThomáis to speak to him about ‘Ireland’s Necropolis’.

IT’S a cold but bright winter morning as I chat with Shane MacThomáis outside the Glasnevin Museum, in the shadow of the great round tower erected over the tomb of Daniel O’Connell. As we talk, an Irish Defence Forces veteran in a smart green blazer and a blue United Nations beret approaches Shane to invite him to a commemoration taking place later that day. “The last time I was here like this I was in the guard of honour for de Valera’s funeral,” he smiles. He and other veterans are there to remember the Niemba Ambush of 1960, when nine Irish Defence Force members were killed by Baluba tribesmen while on UN peace-keeping duties in the Congo. Another veteran, in uniform and clutching a piece of paper with some notes scribbled on it, makes a beeline for our group. Along with taking part in the commemoration, he’s hoping to use this visit to Glasnevin to find out more information about a relative who was buried here in the 1880s.

Prior to the establishment of Glasnevin Cemetery, Irish Catholics had no cemeteries in which to bury their dead. The repressive Penal Laws also meant many Catholics could not perform their full funeral services in public. Daniel O’Connell led a campaign to open a cemetery where Catholics could bury their dead with dignity. After Glasnevin opened in 1832 the first thing he did was to declare it non-denominational, something which was incredibly progressive for the time.

“This cemetery has never refused anybody burial,” says Shane, “and because of that you have all aspects of Irish history here.

“There’s certainly republican history with Young Irelanders, the Land League, the Invincibles, right up to the Tan War and Civil War. But alongside all of that you also have parliamentary politics with people like Charles Stewart Parnell and then you have Ireland’s imperial history: graves of people from the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Crimean War, the Boer War – soldiers who were unionist in their politics.

“The cemetery really encapsulates the whole history of Ireland, not just one aspect.”

Many great rivals, on completely different sides of politics and conflict, found their resting places right next to each other in Glasnevin.

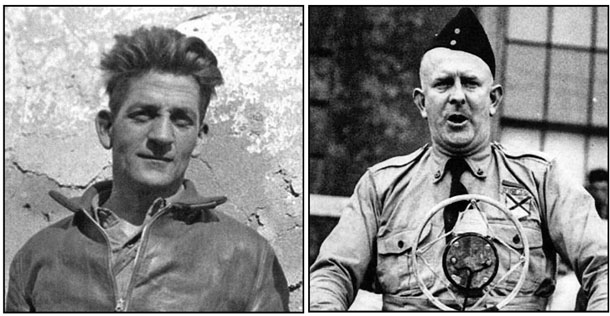

‘Big Jim’ Larkin, the great trade union leader, is buried only 25 feet from his arch-enemy, industrialist William Martin Murphy. Éamonn de Valera is less than 200 feet from Michael Collins, while anti-fascist IRA Volunteer and An Phoblacht Editor Frank Ryan is 50 feet from Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy.

It’s said that, following the passing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty by the Dáil in 1921, representatives of both pro and anti-Treaty sides of the IRA arrived at Glasnevin on the same day to buy up plots in anticipation of the Civil War.

Recently, the Glasnevin Trust was granted €20million by the Government over a period of 10 years for the huge amount of restoration needed to the 20,000 monuments but it only received a portion of that before the economic crash and the election of the Fine Gael and Labour Government. Thankfully, the money the Trust did receive allowed them to finish the museum centre. The ongoing restoration work is financed through tours, book sales, the museum’s coffee shop and the sale of monuments and flowers. “For me it’s a very socialist model,” says Shane. “There isn’t anybody taking a profit from this.”

Shane points across the glass wall along the endless rows of gravestones. He describes two graves which lie next to each other near the chapel. One is of a young man named Emmet, a member of the Irish Volunteers who was killed near Boland’s Mill during the 1916 Rising; the other, named Dunne, is a member of the Dublin Fusiliers killed at the Battle of the Somme that same year.

• An exhibit at Glasnevin Museum shows how grave robbers stole bodies to sell to medical schools

“Both of them could have joined the Irish Volunteers at the Rotunda in 1913,” Shane suggests. “For all we know, they could have been best friends. One went with John Redmond and the other stayed with Pádraig Pearse but they both ended up in unmarked graves here in Glasnevin. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission marked one and the National Graves Association marked the other. Two working-class fellas both end up dead, side by side by 1916, but their politics are completely different.”

Shane says this dichotomy is what he loves about Glasnevin, but it is also a challenge in that the tour guides must give a broad and neutral history – something which can be difficult for people who are passionate and really immersed in their history and politics.

“We get lots of cross-community groups from the North doing shared history projects. Some of those see the South as this monolith of green but when they come down and see graves of a soldier from Dublin who fought in Gallipoli, for example, it breaks down some of the preconceptions that some people have.”

The museum itself contains video and audio displays on those buried within the 124 acres, including interactive screens showing the linkages in life between many of those buried here. Included is Shane’s own father, Éamonn. A well-known and respected author, historian, RTÉ broadcaster and former Editor of An Phoblacht, Éamonn is buried next to another former An Phoblacht Editor, Frank Ryan.

• Frank Ryan is 50 feet from Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy

Other exhibits look at what happens to coffins and bodies after lengths of time below ground. The records held by Glasnevin, stretching back to the 1830s, have been digitised and are fully searchable for those interested in finding out information on their family history.

Inside the museum, Shane brings me into the store room where the cemetery’s original handwritten records are kept. He takes down a large leatherbound ledger dated from 1913. Inside are the records of all those who were buried in Glasnevin during the period of the 1913 Lockout. It’s telling that the majority died of very basic dieases. Shane scans through a few lines in the ledger listing their causes of death. He reels them off: “Bronchitis, TB, kidney disease, childbirth, diarrhoea, pneumonia, TB again, influenza, apendicitis, lockjaw . . .” The likes of Alice Brady, who died after being shot in the hand during the Lockout, is listed as dying from lockjaw – tetanus. Shane puts the ledger back and takes down another huge book. “These are the poor people.” Many of those listed within are children, dying of such things as diarrhoea. One little girl from Charles Street West’s cause of death is listed as “succumbing to marasmus” – severe malnutrition. From August 1913 through to February 1914 the death rate increases sharply, as does infant mortality. Others are listed as “being lain upon”, usually children crushed by parents or other adults as they huddled tightly together for warmth or to get to sleep in the tenements. “These records are really a social history of poverty,” Shane says sadly.

We leave the record room and get into the lift. When we exit upstairs, a group of Transition Year students are getting a lecture on how to conduct a walking tour. They’re being told the importance of hand movements and eye contact in keeping visitors interested – and they’re having a good laugh in the process. “Next week they’ll come back and each one will give a talk on a different grave to a tour group. They’ll get a certificate and everything.” It’s one of the many educational events the museum runs. Shane says that while these events are educational and entertaining, its also very important to be respectful.

• Shane MacThomáis looks through a ledger recording burials in the cemetery in 1913

“Remember, we still bury the dead here, we still cremate, so the trick is to get the balance right. You can’t have a funfair or something like that in a cemetery while somebody is grieving.”

The museum and centre is used by groups from various backgrounds. Recently, Anne Cadwallader’s book Lethal Allies, which exposes shocking levels of collusion between British state forces and unionist death squads, had its Dublin launch here. That was followed shortly afterwards by the Ulster Commemoration Committee’s exhibition ‘The Third Home Rule Crisis: The Unionist Response’ explaining the politics in the North between 1912 and 1914 and the formation of the UVF.

“For me that’s an integral part of Irish history. Without the Ulster crisis and the formation of the UVF we would never have had the 1916 Rising. So it’s about all these things. And there’s nowhere better to do it than a museum where you can have rational debate and discussion.”

For more information on Glasnevin Cemetery Museum and Trust visit www.glasnevintrust.ie