29 September 2013 Edition

Inside stories – Frongoch and Ballykinlar POW camps

Book reviews by Michael Mannion

• Republican prisoners arrive at Frongoch following the 1916 Easter Rising

Liam Ó Duibhir’s new book on Ballykinlar, appropriately titled Prisoners of War, is a fascinating account of the first internment camp for Irish republicans of the 20th century. In an effortlessly readable style, the book describes the British efforts to deny POW status, and the republican strategies to subvert them.

With the Irish in Frongoch. Author: W. J. Brennan-Whitmore. Mercier Press. Price: €14.99

PRISONS and the incarceration of those suspected by the authorities of fostering sedition have always held a special place in the republican consciousness. Jails were regarded as an opportunity to further the struggle in a different theatre of operations rather than ending the prisoners’ participation in the fight.

Names such as Long Kesh, Magilligan, Maghaberry, Portlaoise, The Curragh and many others possess a resonance and instill a sense of pride in the courage, determination and the triumphant human spirit shown by generations of prisoners during the last hundred years of struggle. The very first such location was Frongoch.

Frongoch was a former distillery and (German) prisoner of war camp rapidly adapted after the Easter Rising to accommodate what Britain considered to be the most dangerous of the rebels. Two thousand men were either arrested under arms or subsequently identified as sympathisers and sent to exile in Wales. Thus Frongoch became the original ‘University of Rebellion’.

Without Frongoch, the IRA could not have attained the efficiency and professionalism it was able to demonstrate in 1919.

Personal bonds of friendship were established amongst prisoners

from opposite ends of the country. Command structures and intelligence networks

were established or prepared with strategic planning ready to be implemented as

opportunity arose.

Personal bonds of friendship were established amongst prisoners

from opposite ends of the country. Command structures and intelligence networks

were established or prepared with strategic planning ready to be implemented as

opportunity arose.

The GPO may have been the birthplace of the war for independence but Frongoch was its creche.

This is not a new book. It is a contemporary account written in 1917 that provides a remarkable insight into the lives of the prisoners. The author, W. J. Brennan-Whitmore, was a product of his time and his writing style is ‘high Victorian’, convoluted with many rhetorical asides and incidental quips. He also includes interminable lists of names and locations in the main body of the text, which in a more modern work would be included as appendices or footnotes.

Despite its shortcomings, this book is a valuable historical record of a pivotal moment in Irish history.

• Frongoch internment camp, the original ‘University of Rebellion’

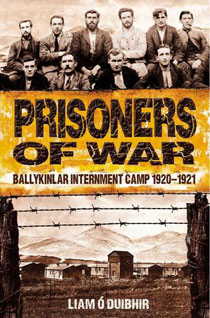

Prisoners of War – Ballykinlar Internment Camp 1920-1921. Author: Liam Ó Duibhir. Mercier Press. Price €19.99

THE British administration in Ireland has a long history of housing political opponents in former military establishments. There they are guarded by soldiers and subject to military discipline yet are constantly told that there is nothing military about their detention. The government assertion is that they are not soldiers – they are criminals or civilian detainees with no possible reason to expect recognition as combatants with political or Prisoner of War status. This is the familiar refrain first developed in Ballykinlar Internment Camp during 1920 and 1921.

Liam Ó Duibhir’s new book on Ballykinlar, appropriately titled Prisoners of War, is a fascinating account of the first internment camp for Irish republicans of the 20th century. In an effortlessly readable style, the book describes the British efforts to deny POW status, and the republican strategies to subvert them.

Although only active for a 12-month period (December 1920 to

December 1921), the harsh conditions in the camp gained a notorious reputation.

During this period over 2,000 men were detained, three prisoners shot dead, and

five more died as a result of inadequate food, cold damp accommodation and

medical neglect.

Although only active for a 12-month period (December 1920 to

December 1921), the harsh conditions in the camp gained a notorious reputation.

During this period over 2,000 men were detained, three prisoners shot dead, and

five more died as a result of inadequate food, cold damp accommodation and

medical neglect.

The organisational abilities of the prisoners seems to have been vastly superior to that of their jailers, which the author attributes to the diversity of backgrounds of the internees. Whilst the British officer class was drawn in the main from one narrow social grouping, the prisoners included priests, doctors, unskilled labourers, university professors, farm labourers and a myriad of other skills. Thus they were able to maintain their own hospital, establish their own currency, run their own church (including forming their own branch of the Society of Vincent de Paul) and, most importantly, control their own canteen.

This is an impeccably researched book, well-written and providing a fascinating account of an often overlooked aspect of the Tan War.

• Within Ballykinlar internment camp, republican prisoners established their own currency, ran their own church (which included a branch of the Society of Vincent de Paul), controlled their own canteen and (seen here) organised their own camp orchestra