29 September 2013 Edition

The rise of the Irish Citizen Army

Remembering the Past

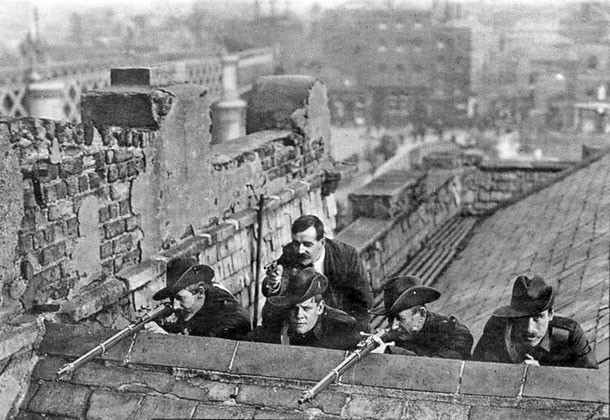

• Irish Citizen Army volunteers training on the roof of Liberty Hall

Even before the Lockout began in August 1913, Jim Larkin spoke of the need for organised defence by workers

ONE of the most significant outcomes of the Great Lockout of 1913 was the establishment of the Irish Citizen Army, the first armed force of organised workers in Irish history and one of the first in the world.

While a newspaper article and two well-documented meetings marked the beginning of the Irish Volunteers, the earlier genesis of the Irish Citizen Army is less clear-cut. Once established, though, it made its mark in no uncertain terms.

During a trade union struggle in Cork in 1908, a defence force of workers had been set up but it was short-lived and local. In his time as a union official and socialist organiser in the United States, James Connolly saw first-hand the use of armed strike-breakers by employers and, on occasions, workers arming in self-defence. The establishment of the Ulster Volunteers early in 1913, armed and officered with the aid of the British Tory Party, brought the gun directly into Irish politics, in addition, of course, to the guns of the occupying British Army and police.

Even before the Lockout began in August 1913, Jim Larkin spoke of the need for organised defence by workers. As soon as the Lockout commenced, workers were attacked. On the very first weekend, two workers, John Byrne and James Nolan, were batoned to death on the Liffey quays by the Dublin Metropolitan Police and hundreds were injured in the infamous DMP baton charge on Bloody Sunday, 31 August. Workers and their families were attacked on the streets, on picket lines, at demonstrations and in their homes.

In one notorious case, the DMP entered Corporation Buildings, a large tenement block in the north inner city near Amiens Street rail station, and beat up its poverty-stricken residents and wrecked their homes. Veteran republican Tom Clarke condemned the police brutality in an indignant letter to the Irish Worker, the ITGWU paper. He described the DMP’s actions as “downright inhuman savagery”. In the Irish Republican Brotherhood newspaper, Irish Freedom, in October 1913, P. H. Pearse wrote in sympathy with the workers and against the employers, the tenement slums and police brutality.

The time was ripe for a workers’ defence force. Citizen Army veteran Frank Robbins in his book Under the Starry Plough (The Academy Press, 1977) recalled:

“One night during October 1913 I attended a meeting in Beresford Place and heard Connolly, speaking from the central window of Liberty Hall, say that as a result of the brutalities of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan Police, it was intended to organise and discipline a force to protect workers’ meetings and to prevent such activities – by armed thugs – occurring in the future. This was the first open declaration I heard regarding the formation of the Irish Citizen Army.”

It was a former soldier in the British Army who had fought in the Boer War who first organised and drilled the workers. He was Jack White, son of a British Army field marshal, and he came from a staunchly unionist background in Broughshane, County Antrim. He was, in his own word, a “misfit”, later in life embracing anarchism but in 1913, as a trained soldier with radical politics and an ability train others, he was in the right place at the right time.

An Industrial Peace Committee had been formed to try to find a settlement to the Lockout. But most of the members, including Joseph Plunkett, the leader executed in 1916, came over to the side of the workers. When the Peace Committee disbanded they formed the Civic Committee and it was at a meeting of this group in Trinity College on 12 November that Jack White proposed the formation of a workers’ defence force.

The next day, Jim Larkin was released from prison and there was a victory parade through Dublin. Addressing the crowd, James Connolly said:

“The next time we go out for a march I want to be accompanied by four battalions of our own men. I want them to have their own corporals and sergeants and men who will be able to ‘form fours’. Why should we not drill men as well as in Ulster?

“When you come to draw your strike pay this week I want every man who is willing to enlist as a soldier to give his name and address, and you will be informed when and where you have to attend for training. I have been promised the assistance of competent chief officers, who will lead us anywhere. I say nothing about arms at present. When we want them, we know where we will find them.”

Soon Jack White was drilling the newly-formed Irish Citizen Army in the grounds of Croydon House, the ITGWU recreation grounds in Fairview (now covered by the Marino housing estate).

The Citizen Army spearheaded the fight against recruitment to the British Army when the European War broke out, symbolised by the banner across Liberty Hall “We Serve Neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland”. The Citizen Army admitted women equally to its ranks. Under Connolly’s guidance it was increasingly politicised, preparing the way for its central role in the 1916 Rising.

The Irish Citizen Army originated during the Great Lockout in October 1913, 100 years ago this month.