2 December 2012 Edition

Partitionist states established

Remembering the Past

• Free State Army officer and Deputy Seán Hales of Cork, pictured just moments before he was shot

Unionist Prime Minister James Craig repudiated the Boundary Commission, upon which many nationalists – including Michael Collins – had pinned their hopes

FOUR DAYS in December 1922 saw tragic events that were the working out of the British Government’s plan to divide and rule Ireland. Partition had been legislated for under the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. At the time of its passing, that Act was a dead letter throughout most of the country, where the Republic had the allegiance of the majority of the people. But in north-east Ulster, the Act led to the establishment of a sectarian Orange state. Partition and the creation of a Six-County state were confirmed in the Treaty that now divided nationalist Ireland.

On 5 December 1922, legislation for the establishment of the Free State was passed at Westminster and the King of England, George V, appointed Tim Healy as Governor-General of the Irish Free State.

The Treaty provided for the formal establishment of the Free State on 6 December. On that day, the Free State parliament assembled and the deputies took the Oath of Allegiance to the English king as set down in the Treaty. A seven-member Executive Council was elected, with WT Cosgrave as President. The next move in the constitutional sequence was made in Belfast.

The unionist Six-County parliament in Belfast formally notified the King of England on 7 December 1922 that they would not be exercising their power to ‘opt in’ to the Free State. Unionist Prime Minister James Craig also repudiated the Boundary Commission, upon which many nationalists – including Michael Collins – had pinned their hopes. They believed that in redrawing the partition boundary the Commission would inevitably make ‘Northern Ireland’ ungovernable - but it was not to be.

The Free State parliament had given to its Army drastic new powers under which eight republican prisoners of war were executed at the end of November. The IRA Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch, wrote to the Speaker of the Free State parliament pointing out that the IRA had treated its prisoners by the recognised rules of war but that IRA prisoners held by the Free State had been tortured and executed. The letter warned that unless the Free State Army recognised the rules of warfare “we shall adopt very drastic measures to protect our forces”.

On 7 December, Deputy Seán Hales of Cork, who was also a top Free State Army officer, was shot dead in Dublin. Another deputy, Pádraig Ó Máille, was wounded. The Free State Government determined to avenge this killing by an act of reprisal. They chose four republicans who had been held in Mountjoy Jail since the summer and could have had no part in the killing of Hales.

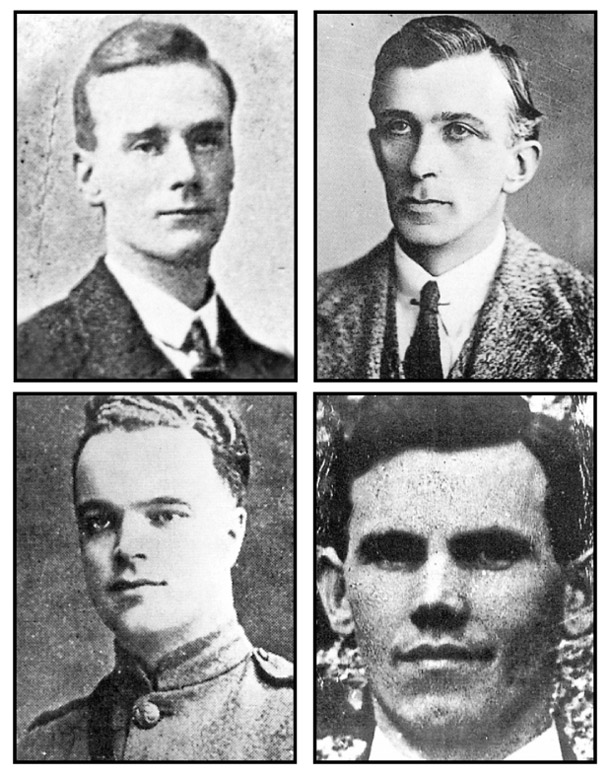

Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey and Richard Barrett were leading members of the IRA and were especially admired by their comrades inside and outside jail. Mellows had begun to develop his thinking on the republican struggle, adapting Connolly’s socialism to the new situation. The men (who would become known as ‘The Four Martyrs’) were taken from their cells in Mountjoy in the early hours of 8 December 1922 and executed by firing squad. The Free State Government stated frankly that the killings were carried out “as a reprisal for the assassination of Brigadier Hales TD”. The family of Seán Hales publicly expressed horror and disgust at the executions.

Britain’s policy of divide and rule came to fruition in the tragic of events of 5, 6, 7 and 8 December, 90 years ago this month.

• The Four Martyrs: Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey and Richard Barrett