2 December 2012 Edition

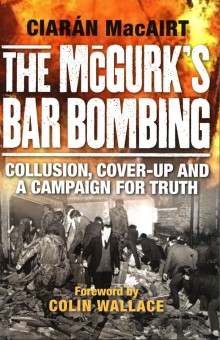

The McGurk’s Bar Bombing: Collusion, cover-up and a campaign for truth

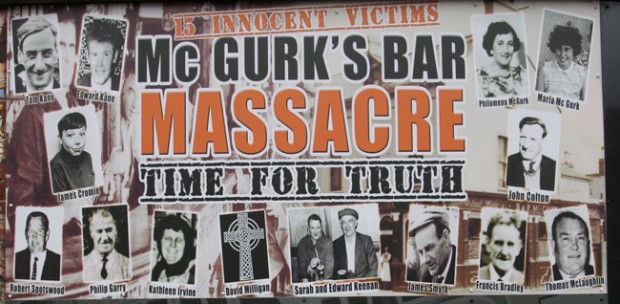

• Those who died: James Cromie (13), Maria McGurk (14), Edward Kane (29), Robert Spotswood (38), Philomena McGurk (46), Thomas Kane (48), John Colton (49), David Milligan (53), Kathleen Irvine (53), Thomas McLaughlin (55), Sarah Keenan (58), James Patrick

If anyone ever believed that the British strategy in the North was about peace-keeping and law and order then the revelations in Ciarán MacAirt’s chapter on information policy will disabuse them of that notion

CONTEXT IS EVERYTHING, without doubt, the message coming out of Ciarán MacAirt’s new book about the UVF bomb attack on McGurk’s Bar in December 1971.

In The McGurk’s Bar Bombing: Collusion, Cover-Up and a Campaign for Truth (Frontline Noir, Price £9.99), MacAirt places the incident in the context of the conflict that was raging our streets at that time.

And as he says himself in his introduction: “The bomb did not explode in a vacuum so I aim to contextualise a moment in time and space.”

The moment in time and space MacAirt sets out to contextualise is that moment at 8:45pm on 4 December 1971 when a UVF bomb ripped through the Tramore Bar on the corner of North Queen Street and Great George’s Street, near the nationalist New Lodge Road in north Belfast. The bar was run by Patrick McGurk.

Fifteen men, women and children were to die in the atrocity that would haunt the British state to this day as the families of the dead and wounded defied the odds and uncovered the truth.

That the families had to fight to uncover the truth lay in the fact that the British state lied about the killings and constructed a propaganda myth around it.

The British sought to blame the IRA for the deaths in line with their evolving ‘black propaganda’ strategy.

From the outset, the RUC and British security chiefs had enough information to know that loyalists were behind the bombing yet decided to spin a web of deceit, based on disinformation.

In his foreword to the book, Colin Wallace, a former senior information officer at the heart of the British Army’s psychological operations unit in the early 1970s, writes:

“If it could be shown that the IRA was directly or indirectly responsible then this would be seen as further justification for internment.”

This is how we begin to understand the real story of the McGurk’s Massacre and its place in the propaganda war being waged by the British Establishment and unionists against the nationalist population of the North.

Where Ciarán MacAirt does us a great service in his book is in the way he brings his personal story and that of all the families to the centre of the British counter-insurgency being employed in the North as they attempted to defeat the IRA and effectively silence nationalist demands for civil rights and equality.

Again, the over-riding framework or context within which the British reacted to the McGurk’s killings is their counter-insurgency strategy built on the theories of Brigadier Frank Kitson.

Described by MacAirt as “a counter-insurgency theorist and practitioner of repute”, Kitson “honed his skills” in the British-ruled colonies of Kenya, Cyprus and Malaya.

He was drafted into the North in 1970 and instigated a methodology that was to become the cornerstone of the British Army’s new approach.

“In-depth interrogation techniques, psychological operations, pseudo-gangs, the murder of civilians by Special Forces units were all instruments of war used by the British military” and are all part of the Kitson handbook, MacAirt notes.

However it is the use of information that is central to the sea-change brought about by Kitson.

This new approach would see information and its management being put at the heart of British military operations in the North.

And if anyone ever believed that the British strategy in the North was about peace-keeping and law and order then the revelations in MacAirt’s chapter on information policy will disabuse them of that notion.

The sinews of collusion, cover-up and lies were all threaded together into an over-arching strategy that went as high as the British Cabinet. This was the blueprint used to ensure the British benefited from the McGurk’s bombing: ‘Blame the IRA for the attack, use it to justify internment, and undermine the cohesion of the Catholic/nationalist community.’

MacAirt, whose grandmother Kitty Irvine was one of those killed, by pulling together this information has lifted the lid on Britain’s dirty war in Ireland. It is a book that must be read.