25 May 2012 Edition

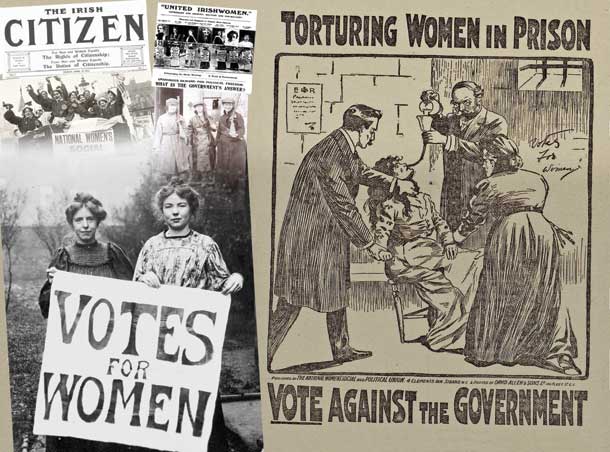

Militant Irish women fight for the vote

Remembering the Past

At 5am, eight IWFL members set off to break the windows in three British Government buildings in Dublin – the GPO, the Customs House and Dublin Castle. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington chose the Castle because it was the centre of British rule. Hanna and Margaret Murphy were arrested by the British Army after breaking several windows in the Castle.

BY THE SUMMER of 1912 it seemed most likely that there would be a Home Rule parliament in Ireland and Irish women were determined to ensure they would win the right to vote in the first election to that parliament. Their campaign was stepped up and took on a new militancy 100 years ago.

The Irish Women’s Franchise League had been established in 1908. Its founders were married couple Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Francis Sheehy Skeffington: she was a gifted academic from a Fenian family; he was a pacifist and feminist who adopted his wife’s name on their marriage, an unheard-of gesture at the time.

The fight for women’s suffrage, the right to vote, had been ongoing in Ireland and Britain since the end of the 19th century. Many women in Ireland supported the campaign but felt the need for a distinctly Irish organisation. The Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL) filled that need because it fed into the mainstream of Irish politics and clearly presented the struggle for women’s rights as an essential part of the struggle for national independence and social justice. Radicals such as James Connolly and Pádraig Pearse supported them.

The IWFL initially focused their campaign on the Irish Parliamentary Party led by John Redmond. The conservative Redmond paid little heed and in March 1912 his party at Westminster voted against a bill which would have given limited voting rights to women, a first step to the full franchise. Two days later, when a massive Home Rule demonstration was held in Dublin, the IWFL women paraded with posters and, at the Mansion House, were set upon viciously by Irish Parliamentary Party stewards.

The day after the women were attacked on the streets of Dublin, an IWFL delegation met John Redmond. He said he was “entirely and utterly” opposed to the insertion in the Home Rule Bill of a clause that would give votes to women. The attack, the Redmond meeting and the barring of the IWFL from a National Convention on Home Rule on 23 April formed a turning point in the IWFL campaign. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington now saw that polite lobbying was futile and more militant action was required.

On 25 May 1912, the first edition of The Irish Citizen, an eight-page weekly journal for the Irish suffrage movement, appeared on the streets. Its motto was: “For men and women equally the rights of citizenship. From men and women equally the duties of citizenship.” In the week following publication a convention was held at which 19 organisations — including women’s groups, trade unions and Sinn Féin — were represented. A final resolution was sent to Irish MPs, again with no response.

On 13 June, the first phase of the more militant campaign began.

At 5am, eight IWFL members set off to break the windows in three British Government buildings in Dublin – the GPO, the Customs House and Dublin Castle. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington chose the Castle because it was the centre of British rule. Hanna and Margaret Murphy were arrested by the British Army after breaking several windows in the Castle.

The first four women went on trial on 20 June and when they refused to pay fines they were sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. They were still in Mountjoy Jail on 18 July when British Prime Minister Arthur Asquith visited Dublin and was greeted with feminist protests. Again they were attacked by Home Rule stewards and it was said that it was unsafe for any woman on the streets of Dublin that day.

Several English suffragists had followed Asquith to Ireland and were jailed for their protests. Gladys Evans and Mary Leigh got five years and began a hunger strike in Mountjoy. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and her three Irish fellow prisoners joined the hunger strike in solidarity. The four Irishwomen were released on 19 August and the prison authorities immediately began to force-feed Evans and Leigh. After 58 days of force-feeding, they were released. This was the first instance of a hunger strike protest and force-feeding in Ireland.

Many of the women involved in the 1912 campaign went on to play leading roles in the 1913 Lock-out, the 1916 Rising and the struggle for Irish freedom. By the time of the 1918 general election, women had won the right to vote and helped to elect the First Dáil Éireann, legislature of the Irish Republic.

• The campaign of Irish women for full citizenship rights was stepped up in June 1912, 100 years ago this month.