6 May 2010 Edition

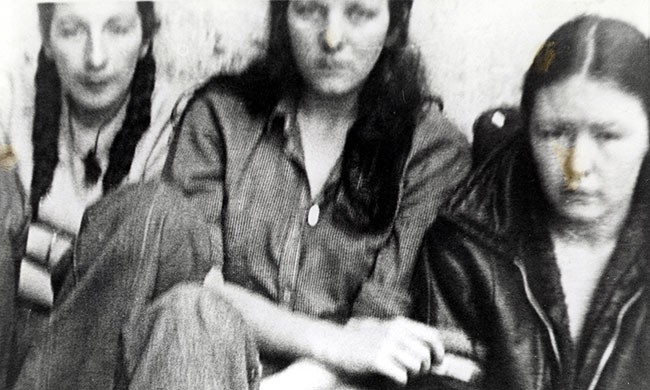

REMEMBERING 1981: The women in Armagh Jail

‘We broke Armagh – it never broke us’

ARMAGH JAIL, like Long Kesh, is closed. Unlike the Kesh, though, there are no plans to maintain any part of it for future posterity, which made it all the more important that some of the first republican political prisoners got a chance to visit the prison before the key was turned for the last time.

ARMAGH JAIL, like Long Kesh, is closed. Unlike the Kesh, though, there are no plans to maintain any part of it for future posterity, which made it all the more important that some of the first republican political prisoners got a chance to visit the prison before the key was turned for the last time.

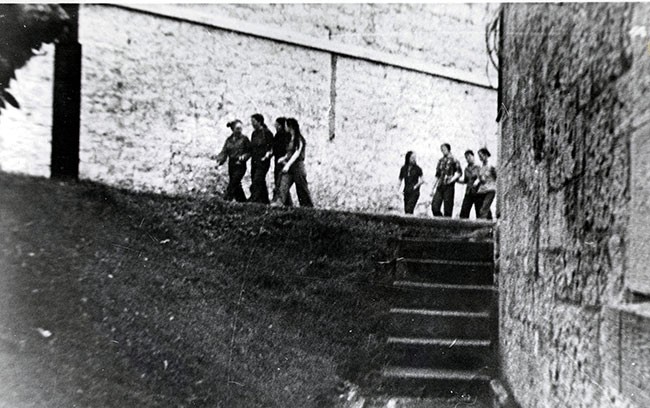

So, on a beautiful late autumn morning, a group of internees and sentenced prisoners began a journey that some of them had only made once before, but which their families had made many times during the women’s years of incarceration.

I had suggested to the group that they should bring a relative with them – almost all brought their daughters so it became ‘The Mother and Daughter Armagh Trip’.

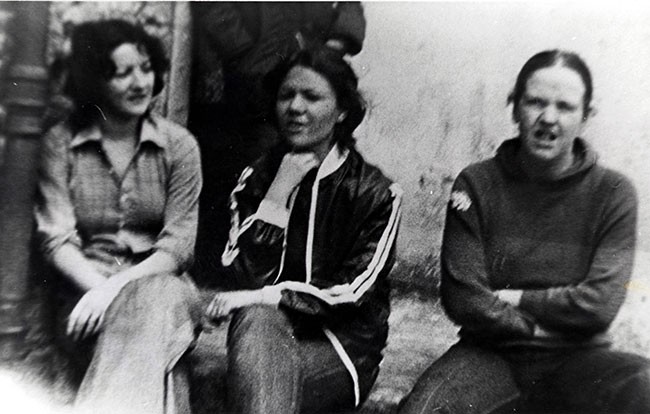

Some of the women were nervously excited as each new face appeared at the top of the stairs. There were screams of recognition and, sadly, sometimes introductions had to be made among old cellmates. The passage of time and geographical location meant that some of them had not met in 30 years.

The journey down passed swiftly as old comrades began the journey back to Armagh and back in time.

One daughter told me that her mother, a former internee, had called her into the kitchen the week before and asked her if she would like to go on the visit to Armagh. She’d said yes and asked her mother if she had ever visited the jail before. Her mother told her no, she hadn’t visited – she had been in it as a political prisoner.

The young woman was aware of and proud of the years her father had spent in prison but she was totally flummoxed by the news that her mother had also been in jail. I was also confused but later in the day I heard a similar tale from a former prisoner.

She explained that she was very young when she went to jail, had married her husband shortly after her release, and had started a family and then her husband went to prison. She felt that the children would worry about her being taken back to jail, so she never told them.

There was much laughter as the women reminisced about escape plans, pre-status days, different governors, and how they graded the Screws on their viciousness.

As we went around the jail, the mood darkened as they remembered some of the worst times.

All of them remembered where their cells had been, and whom they had shared with. They remembered the protests, and they remembered the beatings at the hands of the Screws.

Amongst the group was Pauline Deery, who was the last woman to have political status. Pauline spent a year and a half in a specially-constructed cage on an otherwise empty wing. She was allowed no contact with the other women during all that time.

As the stories were told, I watched as the young women looked at their mothers as if seeing them for the first time, and I saw their tears as their mother and former cellmate chatted away about the night their cell door burst open and a raiding party rushed in, and the gratuitous beatings they received.

As they toured the jail they remarked on how small the cells were, how the chapel seemed to have shrunk, and Ann Marie McWilliams relived the night she saw ‘The Armagh Ghost’.

Or, as I said, the night she thought she saw a ghost. However, she is sure, and if you see her about the road, ask her to tell you about it. All I know is I declined to sit in her cell on my own, but only because we were running out of time. That’s my story anyway.

As we were leaving, I called the women into the courtyard. Having made sure the guide was occupied, I pointed out an intact window to Pauline Deery. “Be a shame to go without leaving your mark,” I said, as I handed her a rock.

Now bear in mind that I was talking symbolism here, and the re-enactment of the Battle of the Bogside that ensued was not my fault. As I was standing behind Pauline, I wasn’t aware that the other 20 women also intended to leave their mark. Suddenly, as the hail of rocks began to sail through the air, I heard the first shout:

“Ye couldn’t break us then and you’ll never break us now!”

And then another:

“Here’s what we think of your strip-searches!”

And another:

“We were political prisoners, no matter what you all said.”

And:

“Where’s Maggie Thatcher now?”

The daughters and I stood back as their mothers vented 30 years of pent-up rage at the institution and the lackeys. I think that’s when some of the daughters realised just what their mammies might have been capable of when they were their age.

As the rock throwing subsided I pointed out that the window was still intact and that clearly none of them had been done for sniping (or maybe they were just out of practice).

I should’ve just left it. Kate McGuinness threw for The Murph. She got a hit.

As the bus was returning to Belfast, the mood was slightly subdued, and I asked them if they were depressed by the visit. They told me no, it was just that it had been so good being together again and that they probably wouldn’t be together again until, as they cheerfully pointed out, “one of us dies and we’re all at the funeral”.

So I’m planning a reunion for them.

My abiding memories of that day will be when they spontaneously sat on the stairs of ‘B’ wing and started to sing together, as they used to every night after lock-up; of Marie Barr’s face as she looked at her mother and Kate McGuinness standing in the cell they shared and hugging each other; of Pauline Deery throwing the first stone in the battle of Armagh (which they had already won) and of looking back into that jail for the very last time; and seeing in my mind’s eye the relentless flow of women who had entered those doors because they wanted to be free.

And I will always cherish the moment after the stoning when one of the women turned to the others and said:

“Armagh thought it would break us – well we’ve broken Armagh.”

Never a truer word.

• The women conquered Armagh