18 December 2008 Edition

Shining a light in cultural darkness

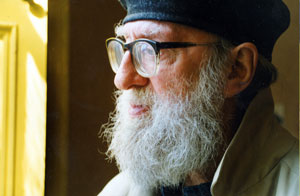

Pearse Hutchinson

POETRY REVIEW

At Least for a While

By Pearse Hutchinson

The Gallery Press

At Least for a While

By Pearse Hutchinson

The Gallery Press

BY MÍCHEÁL

Mac DONNCHA

Mac DONNCHA

MAY we all live to think and write with freshness and insight at 81. The poet Pearse Hutchinson has done so. His latest collection provides an opportunity to take a brief look at his writing life and how his poetry is interwoven with what the artist Robert Ballagh described in a recent television interview as “civic republicanism”.

In a normal society, such concern for social justice, for national identity, for language and history would be fairly unremarkable. We do not live in a normal society but then, I suppose we should ask, who does?

We have unique abnormalities in Ireland and others that are shared by abnormal societies everywhere. For years the shadow of literary censorship, the heavy hand of church and state, loomed large in the life of Irish writers. That ended more or less in the 1960s but it was replaced in the ‘70s and ‘80s by political censorship, more subtle than the book bans that preceded it but no less corrosive.

Many writers went with the flow and reflected the ‘Dublin 4’ outlook. Republicanism was parcelled up with ‘violence’, Catholicism and conservatism and dumped at the bottom of the garden. In a 1988 pamphlet (16 on 16, Raven Arts Press) in which writers reflected on the 1916 Rising, Pearse Hutchinson wrote:

“Brought up to be both a republican and a Catholic, I opted out, fairly early on, of Holy Rome. (The great saint from Bergamo came too late for me.)

“Opting out of Catholic puritanism, I, for a few years in my 20s, identified Irish nationalism with it – a stupid and simplistic mistake (not unlike the simplified, and from the mammonite viewpoint, highly convenient, version of ‘revisionist’ history peddled at us for too long now by politicos and media-pundits).”

ENCOUNTER

Ironic as it may seem, it was because Pearse was outward-looking that he rejected the identification of Irish nationalism with Catholic puritanism. He travelled to Franco’s Spain and became familiar with the submerged nations and suppressed languages of Catalonia and the Basque Country. He has returned to these experiences many times in his writings and has translated from Catalan and several other languages.

Ironic as it may seem, it was because Pearse was outward-looking that he rejected the identification of Irish nationalism with Catholic puritanism. He travelled to Franco’s Spain and became familiar with the submerged nations and suppressed languages of Catalonia and the Basque Country. He has returned to these experiences many times in his writings and has translated from Catalan and several other languages. In a prose poem in his latest collection, Pearse recalls an encounter with a Spanish Civil Guard in Seville in 1951. The elements it brings together highlight several aspects of Pearse’s work:

“Having found out where I came from, he smiled and said:

“‘El alcade que no quiere comer’, meaning: The mayor who doesn’t want to eat. The point of the grim joke being (grim for Spaniards and Irish alike): that was the headline in a Spanish newspaper when Terence MacSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork, died on hunger strike for Irish freedom.

“Whereas Spanish mayors were a byword for gluttony and other forms of rapacity in a Spain full of hungry people.”

‘COCKNEY’

Such incidents, in the hands of a skilful writer like Pearse, become lights that illuminate cultural darkness.

A similar moment is described in Cockney a poem about a young Londoner listening to Pearse arguing about the Irish language:

...in defence of Gaelic against three of its countless

enemies, three proud old-

fashioned young Dublin begrudgers,

then this lad, London’s finest,

cuts (as Dublin’s finest, Brendan

Behan, say, or Jimmy Brennan,

used to cut) right through the shit

with one calm phrase:

‘It’s a language, innit?’

Pearse is a fine poet in Irish also and is scathing of those who disparage the language. Many of his and later generations still moan that they were “turned against Irish” by leather-wielding Christian Brothers and their ilk. But Pearse put it well in that 1988 pamphlet:

“I was forced to learn Irish at school (the Gaelic League via the Easter Rising). I was also forced to study other subjects. I liked languages, so I didn’t get biffed for Irish, or English, or Latin. I did get six on either hand, not with a leather but with, much worse, the leg of a chair, for not being able to sing in tune. It didn’t make me hate music.”

This review highlights some of the politics, in the broad sense, of Pearse’s work. But lest it be thought that he is a ‘political poet’, his range is wide and the depth of his work is in his keen understanding and skilled crafting of language.

He has lived in the same house in Rathmines since 1932 yet in April in this collection he can look anew at dandelions and a magpie in his garden and make a poem that delights the reader.

Pearse has produced many short, polished poems. This one is a suitable end for this review and an appropriate epitaph for the Celtic Tiger:

Shamrock and Harp

Music and a small plant

we had for emblems once.

Better, surely,

than lion or eagle.

Now our proudest boast

is a dangerous beast of prey.