21 August 2008 Edition

1981 Hunger Strike : 27th Anniversay

Towards a United Ireland

BY DALE MOORE

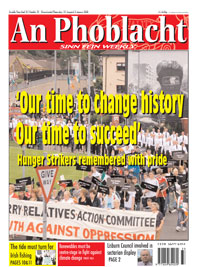

The first National Hunger Strike commemoration to take place outside Belfast was attended by several thousand people from across the country in Derry City on Sunday, 17 August. In stark contrast to the wet weather that caused severe flooding across the country, the day remained dry and warm with the sun even making an appearance encouraging many families to come out and take part.

With 17 bands from as far away as Glasgow and Wexford and imaginative floats including the commemorative 1950s Brookborough Raid lorry there was a carnival atmosphere as the march departed the Creggan shops.

The parade was led by families of the 1981 Hunger Strikers and Derry Sinn Féin members carrying a banner proclaiming the theme of the March – ‘Civil Rights, Equality, Freedom-The Struggle Continues’. They were accompanied by two women Carol Harkin and Kathleen Deeney who marched the route wrapped in blankets as they did many times throughout the periods of the 1981 Hunger Strike itself.

A large delegation of young republican activists followed while children held placards with the names and sentences of republican prisoners. This was followed by a large contingent of former prisoners and republican activists dressed in black ties and white shirts.

A large delegation of Basque political activists with flags added an international flavour and the many Sinn Féin Cumann banners, made an impressive site as the march snaked its way to the Brandywell.

Many homes in the Creggan flew the Tricolour and lampposts bore the names of the Hunger Strikers and images of 1981. The parade paused at the home of Michael Devine, the last of the Long Kesh martyrs to die, before continuing to the Brandywell and passing the spot were two IRA Volunteers died in action in May 1981.

The parade stopped briefly at the home of Patsy O’Hara the fourth of the Hunger Strikers and passed a new mural by Ógra Shinn Féin to the ten brave men.

As the March looped down the flyover into the Bogside it passed Free Derry Wall and then stopped briefly at the Hunger Strike monument where a lone piper played amongst other tunes I’ll Wear No Convicts Uniform.

Wreaths were laid on behalf of the Republican Movement and families and friends of the Hunger Strikers. Before moving on to the Gasyard for the orations the parade passed a mock H-Block cell outlining the stark conditions the men in Long Kesh and the women in Armagh had to endure at this period.

Chaired by former hunger striker Raymond McCartney proceedings got under way with Sarah Griffin singing Death Before Revenge before Ógra Shinn Féin members Shilena Toland and Padraig Barton read the Roll of Honour.

The main address was delivered by Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams who extended a special welcome to the families of the 1981 Hunger Strikers and also to the families of those victims bereaved by British state forces directly or as a consequence of their collusion with unionist death squads.

He said that it was appropriate, given that five of the Hunger Strikers are from County Derry and two, Patsy O’ Hara and Micky Devine, are from the city, that the first national Hunger Strike march and rally outside Belfast, should take place there.

Below we reprint a slightly edited version of Gerry Adams’ address: The people of Derry endured much before and during the years of conflict.

The people of Derry endured much before and during the years of conflict.

After partition the British government set about the creation of an apartheid, corrupt little sectarian state in which Catholics were treated as second class citizens. The unionist party were the caretakers.

They governed a state in which tens of thousands were denied the right to vote, or a job or a home because they were Catholic and deemed nationalist.

This City represented all that in a very graphic way. It was a nationalist city run by a unionist elite! In response to this much of the energy and drive of the Civil Rights movement was in this city.

I remember, like it was yesterday, the 5 October Civil Rights march in 1968 – 40 years ago this October – which took place on the eve of my 20th birthday.

The brutal attack by the RUC on peaceful marchers, caught on television for the first time, was stark evidence of the refusal of the unionist state and of unionist politicians to agree to the necessary fundamental reforms.

As a result of this failure the North slipped into decades of conflict. And Derry was frequently in the front line. During internment hundreds were imprisoned from this city and county. Shoot-to-kill actions, the worst being Bloody Sunday; plastic bullet killings; paid perjurors; house raids and harassment and the torture of local men and women and much more were part of the daily lives of families here.

Lean Poblachtanaigh agus naisiunaithe na cathrach seo ar aghaidh – dílís agus neamhbriste trid ré corrach.

Bhí sibh croiúil, cróga.

Skip forward 40 years and the change has been remarkable. Of course, British jurisdiction in Ireland and other issues of injustice, of disadvantage, of poverty and underfunding in public services, continue to be major problems which need to be resolved. They are part of the legacy of partition and of British government involvement in our country. But the reality is that the Peace Process and the agreements that have emerged out of it have wrought profound change. And the challenge for all of us in the time ahead is to use these agreements to bring about even greater change.

This annual march and rally has its roots in two major historic events in the last, almost 40 years of struggle and conflict. One is the Hunger Strikes of ‘81. The other is internment. In August 1971 the British government introduced internment at the behest of the unionist regime. It was a catastrophic decision which saw a dramatic escalation in the conflict. Its human cost on families and communities across the North was incalculable.

Thirty six years ago British Paratroopers were unleashed on the people of Derry. Thirteen men were murdered in the name of the British Government that terrible day and two later died as a result of the injuries inflicted. The consequences of 30 January 1972 were so far-reaching that the repercussions catapulted us into a spiral of conflict that left few in Ireland untouched. Because truth was also a casualty that day and the denial of truth is a denial of justice.

Last Saturday I attended an event in Ballymurphy, in west Belfast, organised by the families of 11 people killed by the same British Army’s Parachute Regiment in the 48 hours after internment began. All 11 were civilians. One was the local parish priest, another was a mother of 8 children. Forty seven children were left without a parent.

And like Bloody Sunday and so many other similar incidents there was a cover-up of the circumstances. In the last few years these families have come together to organise and campaign for the truth.

The Ballymurphy Massacre Committee is demanding an Independent International Investigation into all of the circumstances surrounding these deaths and for the British government to issue a statement of innocence and a public apology.

They are not alone. Countless hundreds of other families are similarly demanding truth. Many are victims of collusion and British state violence. Sinn Féin supports them in this endeavour.

It is clear that significant elements of political unionism are deeply uncomfortable with where unionism is today. Traditionally, historically, unionism in this city and elsewhere has been about constantly saying ‘No’ and about domination.

There are some – particularly within the DUP – who would like a return to the old days, and to the old ways of majority unionist rule – it isn’t going to happen.

There are some – particularly within the DUP – who would like a return to the old days, and to the old ways of majority unionist rule – it isn’t going to happen.

Tá na laethanta sin thart.

Today the DUP finds itself in a place it never wanted to be – a partnership government – in which a DUP Minister has an equal status with a Sinn Féin Minister in the Joint Office of First and deputy First Minister. Tá Sinn Féin iontach soileir ar ár gcuspóirí, ar an bhealach chun tosaigh, ar ár mbeartaoíochta agus ar na dúthshláin atá romhain.

At times all of this means that the process of change is slow – certainly much slower than the vast majority of citizens want. One example of this is Acht na Gaeilge. Another is the transfer of powers on policing and justice. In my opinion the vast majority of citizens want the transfer of powers to take place; they want the institutions to be delivering for them on all these matters, as well as on other bread and butter issues; like rising energy costs and the crisis on the housing market. There is, therefore, an understandable frustration and annoyance, and not just among nationalists and republicans, at the lack of progress and at the DUP’s refusal to engage properly.

For our part Sinn Féin will not shirk our responsibilities nor bow to unionist intransigence. The message to unionism is clear – if unionists want to exercise power; if they want an Assembly, and an Executive, taking meaningful decisions, then there is a price to be paid – and that price is sharing power with republicans in a partnership government of equals.

Anything less is not acceptable and anything less will not work.

Sinn Féin’s goal is a United Ireland. Togfaí tochaí na hEireann ar bhunchloch chearta saoranaigh do gach duine a chónaíonn ar an oileán seo.

Republicans and democrats believe it is in the best interests of all the people who live on this island that British government interference and jurisdiction are ended. To advance this goal means developing an entirely new relationship with unionism.

A chairde, we have come a long way and we have a lot of work ahead of us.

The most important challenge facing us is the challenge of nation building. Republicans have a vision of a new future, a better future, and we have the spirit and the confidence born out of decades of struggle to achieve this.

The two key words – concepts – of our republican future are ‘change’ and ‘equality’. Republicans are for positive change – progressive and deep rooted. We are for an Ireland with core values which uphold the well being of the aged, and the advancement of youth, the liberation of women and the protection of our children, where all citizens are treated equally. Our past was built on colonialism, dispossession, discrimination and division. Our future has to be different. Our future is a future together.

To succeed we have to take this republican message of hope and change, of progress and equality, and of freedom; to every corner of this island; and to every citizen. And everyone here can play a part in that.

As Bobby Sands put it: “Everyone, republican or otherwise has his own particular part to play. No part is too great or too small, no one is too old or too young to do something.”

41 years ago, as a young republican activist I attended the meeting in Belfast from which emerged the Civil Rights Association. Forty years is a long time in a person’s life. But it is only a blink in the history of struggle.

Today we can take great confidence from the reality that republicanism is bigger and more popular than in generations; and is ready to achieve what previous generations only dreamed of. This is in many ways due to the huge courage and sacrifices of the hunger strikers and their families.

Is fir spreagúla iad – thug said sampla duinn uilig sna laethanta gruama,dorcha sin i naoi deag ochtó a haon, chuir said i néadan Rialtas crúalach, gránna na Sasanaigh i nÉirinn. Tá cuimhne ar Thatcher ar an náire a tharraing sí ar a tír fein agus ar an chruáileacht a thaispeáin sí do tír s’againn.

For their part the hunger strikers are remembered with pride by freedom loving people every where.

Even in the worst of times and the worst of conditions they never gave up.

More than that they were confident of success, and they succeeded.

Well, this is our time to succeed. This is our time to change history.

The ceremony was brought to a close with Sarah Griffin singing Amhrán Na bhFiann.