20 December 2007 Edition

Rambling Jack - the Fenian Balladeer

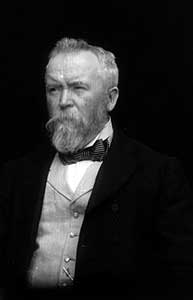

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa

Irish Republican Brotherhood 150th anniversary

With 2008 marking the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, Mícheál MacDonncha recalls a forgotten Fenian whose life spanned the decades from before the Great Hunger to within living memory of our own time.

The Fenian Rising of 1867 was a military fiasco but it had profound long-term political consequences. The personal consequences for individual Fenians were equally profound. For the Fenians immediately involved in the Rising it entailed death for some, imprisonment for many and exile for countless numbers. Those of whom we know least are the rank and file who remained in Ireland and led lives of poverty because of their dedication to Irish freedom. But one such forgotten freedom fighter emerges from the past and his story conveys to us something of the defiant spirit of Fenianism.

Edmond Houlihan was born in Darnstown, Kilmallock, County Limerick in 1839, the year of a storm that devastated much of Ireland, giving it the title Bliain na Gaoithe Móire. His family must have been spared the worst horrors of the Great Hunger but being in the heart of Munster they would have witnessed the disease, the starvation, the evictions and the mass exodus of the destitute. The Irish people had been told by their political leader Daniel O’Connell and by the Catholic Hierarchy that bloodshed for a political cause was a sin against God and that private property was sacred. So they starved while hardly a stick or a stone was lifted to prevent the export of Irish crops, meat and livestock to feed industrial England and to pay rents to landlords.

This experience bred a fierce spirit of resistance and a determination to reassert the rights of the Irish people. The political manifestation of that spirit and that determination was the Irish Republican Brotherhood, founded in Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day 1858. It spread quickly throughout the country. The members of the clandestine IRB also organised in open societies such as the National Brotherhood of St. Patrick which had a branch in Kilmallock founded by a Baptist minister about 1860.

By 1865 the Fenians were well established in the district and had an arms depot at Kilmallock. The local Fenian ‘centre’ or leader was Willie Wall and he was deported from Ireland by the British in that year. In 1866 another local IRB man, Nicholas Gaffney, went to America to avoid arrest and took part in the Fenian raid on Canada led by Colonel John O’Neill.

Hundreds of Irishmen who had served in the American armies during the Civil War returned to Ireland to take part in the Fenian Rising. They were sent around the country to lead the local forces when the long-postponed insurrection was set for March 1867. Captain John Dunne, a native of Ráth Lúirc on the Cork-Limerick border, took command of the south-east Limerick area and planned to capture the heavily fortified RIC barracks in Kilmallock.

Dunne led a large force to Kilmallock on 6 March. One of them was Edmond Houlihan. The Fenians had scores of long-handled pikes but few firearms and no explosives with which to attack the fortified barracks. They fired on the building with their few guns and attempted to set the door alight. The siege went on for hours but the building remained impregnable. Then RIC reinforcements arrived and the Fenians were forced to withdraw under heavy fire.

Three Fenians died in the Kilmallock siege – Dr. Clery, Daniel Blake of Bruree and a third man whose name is uncertain and who is remembered on a memorial in the local graveyard as ‘the Unknown Fenian’. Poet Michael Hogan wrote about him:

Who daringly breasted the fire of the foe?

Like a veteran inured to the battle’s grim danger

He fought ‘til the red hail of death laid him low.

After the fight some of the Fenians, including Dunne, escaped to America. But a large number were rounded up and tried by a Special Commission in May 1867. They were sentenced to terms ranging from 15 years penal servitude to five years. Sentenced to ten years, Daniel Bradley, told the court:

“I am satisfied to abide by the result. I am sure I did right when I took up arms for the Irish Republic.”

A very different sentence awaited Edmond Houlihan. In the fight at Kilmallock he was wounded and lost his sight. Clearly of independent spirit this young Fenian was determined not to face a life in the poorhouse or be a future dependent on already hard-pressed relatives. So he took to the roads of Ireland as a wandering singer and musician. He is described as a tall man with an athletic figure and a rich baritone voice. He played the fiddle and with this instrument and with his powerful singing voice he earned a living travelling the country, mainly around the Midlands, where he became legendary as ‘Rambling Jack’.

Edmond Houlihan’s mission was not only to earn a living. What we know of him comes from an acquaintance, Patrick Fanning of Ferbane, who wrote:

“The fiddle, which before the Kilmallock accident, had been his amusement, became for him afterwards, through more than 50 years, an instrument in the cause of Irish independence. When he could no longer use the sword, no power on earth could prevent him using his powerful baritone voice.” (Offaly Independent, 10 January 1953).

In a country where literacy was limited and where newspapers had not yet reached a mass audience the travelling ballad singers played an important role in conveying news and opinions. In a nation often in political ferment as Ireland was in the late 19th and early 20th century this role was even more significant. Many a singer, including, we are told, Edmond Houlihan, was arrested by the RIC for singing ‘seditious’ songs.

A national teacher with 13 years service in County Tipperary was dismissed from her post in 1868 when the RIC found in her mother’s house a copy of a ballad on the prison escape of Fenian leader James Stephens:

Which way did Stephens go, says the Shan Van Vocht

When from Richmond snug and tight

He walked off out of sight

And never said ‘good night!’, says the Shan Van Vocht.

We know many of the songs such as this which Rambling Jack sang or was likely to have sung. “Who that ever heard him can forget him at the Smashing of the Van?” wrote Fanning. The three Manchester Martyrs Allen, Larkin and O’Brien were executed in the November of the year Rambling Jack was blinded. No doubt this song would have meant much to him and to his listeners:

I’ll sing to you the praises of the sons of Erin’s Isle

It’s of those gallant heroes who voluntarily ran

To release two Irish Fenians from an English prison van.

On the eighteenth of September, it was a dreadful year

When sorrow and excitement ran throughout all Lancashire

At a gathering of the Irish boys they volunteered each man

To release those Irish prisoners out of the prison van.

Closer still to Houlihan’s heart and closer to home would have been The Ballad of Peter O’Neill Crowley the Fenian leader killed in the fight at Kilclooney Wood, County Cork, not far distant from Kilmallock on 31 March 1867.

Who stepped into Kilclooney Wood that day along with you

Who stood behind that broad oak tree and fired that signal gun

Who fought and died for Ireland, ‘twas you my darling son.

God rest you Peter Crowley, you sleep beneath the clay

But some day you’ll return again to lead us in the fray

With a thousand men at your command be they all both brave and true

And we’ll drive the English from our land as Irishmen can do.

The anti-recruiting ballad is one of the great strains of Irish resistance songs. The story is told that in Ferbane, County Offaly, Rambling Jack defied the British Army when he sang an anti-recruiting song as a recruiting meeting was about to begin in the main street. The song was one of the finest, Patrick Sheehan, by Charles Joseph Kickham, the Tipperary Fenian who was the foremost writer on the IRB newspaper The Irish People. Both Kickham, who was partially blind and deaf, and Edmond Houlihan, would have identified with the character in this song, a young Irishman blinded fighting in the British Army in the Crimea:

Tipperary is my native place, not far from Galtymore;

I came of honest parents, but now they’re lying low;

Though’ many’s the pleasant days we spent in the Glen of Aherlow.

Bereft of home and kith and kin, with plenty all around,

I starved within my cabin, and slept upon the ground;

But cruel as my lot was, I never did hardship know,

Till I joined the English army, far away from Aherlow.

I tried to find my musket, how dark I thought the night!

O blessed God! It wasn’t dark, it was the broad daylight!

And when I found that I was blind, my tears began to flow,

And I longed for even a pauper’s grave in the Glen of Aherlow.

So Irish youths, dear countrymen, take heed of what I say;

For if you join the English ranks, you’ll surely rue the day

And whenever you are tempted, a-soldiering to go.

Remember poor blind Sheehan from the Glen of Aherlow.

The manager of The Irish People was Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa the Cork Fenian who endured horrific conditions in English prisons before exile in America. The song about Rossa is listed by Fanning as one of Rambling Jack’s standards. Unusually for a rebel ballad it lists a number of informers, the bane of the Fenian Movement:

I’d throw a rope around their necks and drown them in the bay.

There was Nagle, Massey, Corydon and Talbot – he makes four

Like demons for their thirst for gold they’re punished evermore.

Let no man blame the turnkey nor any of the men

There’s no one knows but two of us the man who served my friend

I robbed no man, I spilt no blood tho’ they sent me to jail

Because I was O’Donovan Rossa and a son of Granuaile.

Not mentioned in that song is another informer, James Carey, who turned Queen’s evidence against the Invincibles who were responsible for the assassination of senior British officials Cavendish and Burke in the Phoenix Park in 1882. Pat O’Donnell of Mín an Chladaigh, County Donegal pursued Carey when he was brought to supposed safety on board ship to South Africa. O’Donnell shot Carey dead, was arrested and executed in London in December 1883. He shouted in court: “Three cheers for old Ireland! Hurrah for the United States! To hell with the British Crown!”

I am you know a venomous foe to traitors one and all.

For the shooting of James Carey I was tried in London town

And now upon the gallows high my life I must lay down.

I sailed on board the ship Melrose, in August eighty-three

Before I landed in Cape Town it came well-known to me

When I saw he was James Carey we had angry words and blows

The villain, he tried to take my life on board the ship Melrose.

We know that Rambling Jack sang this song and that, like O’Donnell, he was a fluent Irish speaker and sang in Irish as well as in English. What songs in Irish he had we are not told but we may be virtually certain that he sang Sliabh na mBan which commemorates the 1798 Rising in Tipperary when the United Irishmen were routed by the British on the slopes of the mountain.

Do dhul ar Ghaeil bhochta is na céadta slad

Mar tá na méirligh ag déanamh game dinn

á rá nach aon ní leo pike nó sleá

Níor tháinig ár major i dtús an lae chugainn

Is ní rabhamar féin ann i gcóir ná i gceart

Ach mar sheolfaí aoireacht bó gan aoire

Ar thaoth na gréine de Shliabh na mBan.

Is tá an Francach faobhrach is an loingeas gléasta

Le cranna géara acu ar muir le seal

‘Sé an síorscéal go bhfuil a dtriall ar éirinn

Is go gcuirfid Gaeil bhocht arís ‘na gceart

Dá mba dhóigh liom féineach go mb’fhíor an scéal úd

Bheadh mo chroí chomh héadrom le lon an sceach

Go mbeadh cloí ar mheirligh, is an adharc á séideadh

Ar thaobh na gréine de Shliabh na mBan.

One of the most remarkable things about Rambling Jack was his longevity. At the age of 76 he was still travelling the roads because we know that in that year he played his way across the country to attend the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa in August 1915. He heard Pearse’s oration in Glasnevin Cemetery and often quoted from it. And he was still defying the British Army recruiters and their supporters. In a Westmeath village in 1915 or 1916 his fiddle was seized and smashed when a group of West Britons objected to his rebel songs.

Rambling Jack ended his travels when he fell ill in 1929. He returned to County Limerick where he lived out the last two years of his life and died on 27 December 1931. He is buried in Kilbreedy Cemetery, a few miles east of Kilmallock. He was himself one of those of whom he so often sang - The Bold Fenian Men:

When our hills never echoed the tread of a slave

On many green hills where the leaden hail rattled

Through the red gap of glory they marched to their grave,

And we who inherit

Their name and their spirit

Will march ‘neath their banners of liberty then

All who love Saxon law

Native or Sassenach

Must out and make way for the Bold Fenian Men.