14 October 2004 Edition

Determined revolutionary

BY Mícheál MacDonncha

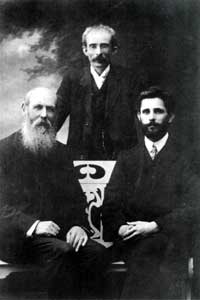

Seán MacDiarmada pictured with Tom Clarke (centre) and John Daly

Book Review

Seán Mac Diarmada -

the Mind of the Revolution

By Gerard MacAtasney

Drumlin Publications (Leitrim)

This is the first comprehensive biography of Seán Mac Diarmada, signatory of the Proclamation of the Republic and, in many ways, as the title suggests, the mind behind the 1916 Rising.

While the author is probably going too far in saying that Mac Diarmada has been neglected by historians, he is right to assert that he deserves a lot more attention than he has received. This biography certainly redresses the balance and it is a most comprehensive and thoroughly documented account. The author has made great use, in particular, of British Government papers, including RIC surveillance notes, and the accounts of 1916 and Tan War veterans in the Bureau of Military History in Dublin. Many of these sources were not available to earlier historians.

What emerges from this book is a complete picture of a very determined revolutionary. While there are no dramatic new revelations, the book deepens our knowledge of Mac Diarmada. It also provides an insight into the political and cultural organisations which made the Irish National Revival in the early years of the 20th Century. Mac Diarmada was a key figure in several of them, infusing all with his republican zeal.

Born in Kiltyclogher, County Leitrim, on the border with Fermanagh, Mac Diarmada moved to Belfast where he worked on the trams. Like most of his contemporaries, as a youth, Mac Diarmada was a supporter of the United Irish League (Home Rulers) and was a member of their vehicle, the Ancient Order of Hibernians. This sectarian outfit was a kind of Catholic imitation of the Orange Order and was headed by UIL MP for West Belfast, Joe Devlin. But it was in Belfast that Mac Diarmada was politicised, left the Hibernians and became a republican. He joined the Dungannon Clubs, which had a significant membership of Protestant republicans, including Bulmer Hobson.

That was 1905, the year the Dungannon Clubs were founded, and the year Sinn Féin was established. With the UIL in the ascendancy, republicanism was at a very low ebb. The book quotes RIC surveillance notes of an attendance of only 80 people at the Wolfe Tone commemoration in Bodenstown that year, showing "the failure of treasonable or revolutionary demonstrations in Ireland at the present day". Mac Diarmada was determined to change all that and he devoted himself unceasingly to the task for the next eleven years.

A member of Conradh na Gaeilge and Cumann Lúthchleas Gael, as well as the Dungannon Clubs, Mac Diarmada was in a pivotal position to help to shape the new Ireland. But it was in the Irish Republican Brotherhood and in Sinn Féin that he really made his mark. He was a travelling organiser for Sinn Féin and journeyed the length and breadth of the country, where he became well known. He earned the respect of many when he directed the Sinn Féin election campaign in North Leitrim in 1908, in a Westminster by-election that saw the party mount its first challenge to the UIL. While it did not succeed, it received a respectable vote that signalled its arrival as a significant element in Irish politics. (The election is described in another Drumlin Publications book, Sinn Féin - the First Election by Ciarán Ó Duibhir.)

The UIL was blatant in its use of sectarianism in North Leitrim. The Sinn Féin candidate was denounced from pulpit and press and Protestant republicans were described as "Orangemen". This, and his earlier experience with the Dungannon Clubs, alienated Mac Diarmada from the Catholic clergy and like the Fenians by whom he was inspired, he was not afraid to challenge the political position of the Church. On one occasion he had a priest 'detained' by two IRB men to prevent him giving evidence that would have convicted another IRB member of possession of explosives.

By 1909, Mac Diarmada was national organiser of Sinn Féin. But it was his close relationship with Tom Clarke that was to set the course of the remainder of his life. Together, they revived the moribund IRB and refocused it on its original objective — an armed insurrection against British rule in Ireland. They established Irish Freedom newspaper in 1910, with Mac Diarmada as its manager. The following year he was struck by polio, which left him with a disability for the rest of his life. He could walk only with the aid of a stick.

When the Irish Party held the balance of power at Westminster and were able to negotiate a Home Rule bill with the Liberal Government, it seemed that the republican star might be on the wane over Ireland. But the Tory/Unionist reaction turned the wheel of history and when the Irish Volunteers were established in 1913, Mac Diarmada and the IRB were in key positions. Redmond's attempted takeover of the Volunteers, and Hobson's acquiesence, ended Mac Diarmada's friendship with his former Dungannon Clubs comrade. Hobson's bitterness is evident in the extracts from his memoirs that are referred to in the book.

Mac Diarmada's role in planning the 1916 Rising was crucial. As the author points out, while he and Pearse and others used the rhetoric of sacrifice, they planned meticulously to succeed. The Rising was never conceived as only a gesture. When the plans fell apart at the last minute, they made the courageous decision to proceed and courageously faced death before the British firing squads.

This relatively short book is packed with information and heavily footnoted. The author concludes with an assessment of his subject. I think this would have been better done during the course of the narrative which, at times, proceeds at too hectic a pace. A closer linkage of narrative and assessment might also have given the author second thoughts about some of his more questionable conclusions.

In correspondence to Joe McGarrity in America, Mac Diarmada was critical of Larkin during the 1913 Lockout. His view of that struggle was fundamentally flawed. However, the author is not correct to say that according to the Sinn Féin philosophy of the time "any form of workers solidarity was anathema and the antithesis of Irish self-sufficiency". In fact, there were many Sinn Féin trade unionists. I do not believe the author is correct either, when he says that "for Mac Diarmada and others socialism was the antithesis of nationalism". McAtasney neglects to mention the support for the workers expressed by Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt and other republicans.

For republicans like Mac Diarmada, the antithesis of nationalism was not socialism but imperialism. They recognised in Connolly a great anti-imperialist. Curiously, the author has little to say about the role of James Connolly in the Rising and books by and about Connolly are absent from the list of sources.

The author asserts that Mac Diarmada had a "personal antipathy" towards Pearse but bases this claim on flimsy evidence. He offers only an account by Kathleen Clarke, Tom Clarke's widow, of a very brief remembered conversation between Tom and Seán. Even if this is accepted at face value it is not proof of personal antipathy, still less Mac Diarmada's opposition to a proposal in 1915 that Pearse be made president of the IRB.

The author includes a very questionable account, recently come to light, based on the reported recollection of a British soldier in the autumn of 1916. He claimed that Mac Diarmada and Connolly were executed together and that Connolly was shot on a stretcher. This is contradicted by all other accounts, which agree that they were executed separately and that Connolly was on a chair.

These reservations aside, I would recommend this book highly and the author and publishers deserve praise for this long overdue complete biography. It is timely on the eve of the centenary of Sinn Féin and it is fitting tribute to an Irish revolutionary whose work has yet to be completed.

Mac Diarmada's letter to John Daly on the eve of his execution

My dear Daly,

Just a wee note to bid you Good Bye. I expect in a few hours to join Tom [Clarke] and the others in a better world. I have been sentenced to a soldier's death - to be shot tomorrow morning. I have nothing to say about this only that I look on it as part of the day's work. We die that the Irish nation may live. Our blood will rebaptise and reinvigorate the old land. Knowing this it is superfloous to say how happy I feel. I know now what I have always felt - that the Irish nation can never die. Let present-day place-hunters condermn our action as they will, posterity will judge us aright from the effects of our action....