31 July 2017

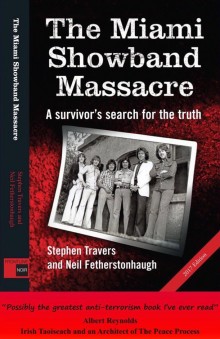

The Miami Showband Massacre, 31 July 1975 – A survivor’s search for the truth

● One of the last photos of the Miami Showband before the massacre: Steve Travers, Tony Geraghty, Ray Millar, Brian McCoy, Fran O’Toole, Des Lee

‘We were halfway to Newry when we were stopped at a UDR roadblock . . . a regular roadblock with uniformed UDR soldiers present’

THE Miami Showband Massacre took place 31 July 1975, near Newry, in south Armagh, while the band was travelling home to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge, County Down.

Their tour bus was stopped at a roadblock, flagged down by men who were not only serving soldiers in the British Army’s Ulster Defence Regiment but active members of a unionist death squad, the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Two soldiers planted a bomb in the bus but it exploded prematurely and killed them outright. Three members of the Miami, one of the most popular showbands in Ireland at the time, were then gunned down by the other soldiers.

Teenage heart-throb and lead singer Fran O’Toole (29) and trumpet players Tony Geraghty (23) and Brian McCoy (32) were killed by the UDR soldiers.

There are still unanswered questions about that night – why did it happen, who was behind it all, and who was the mysterious professional British Army officer with the clipped English accent who gave orders at the murder scene?

The Miami Showband Massacre: A Survivor’s Search for the Truth, has been written by Stephen Travers, who was wounded but survived the attack, and Dublin journalist Neil Fetherstonhaugh.

ELLA O’DWYER spoke to Stephen Travers about an event that shocked a nation.

● ● ●

STEPHEN TRAVERS (pictured) joined the Miami Showband as its new bass player only two months before the atrocity.

From Carrick on Suir, in County Tipperary, he was 24. The band was hugely popular and attracted crowds of young people to dance-floors the length and breadth of Ireland. Despite ‘The Troubles’, the Miami regularly played in the North.

Stephen Travers recalls what happened in the early hours of 31 July 1975 as the band travelled south after another successful gig, in Banbridge. It was after 2:30am in the morning.

“We were halfway to Newry when we were stopped at a UDR roadblock. There have been misconceptions regarding issues around the whole event and that’s one of the reasons for getting the book out. I want to set the record straight.

“For instance, some people think the roadblock was a bogus one. It was, in fact, a regular roadblock with uniformed UDR soldiers present.

“We were told to get out of the minibus and line up alongside it.”

Initially, things looked normal enough.

“At the start, the UDR men seemed relaxed and confident, joking and having the craic basically.”

While the boys in the band were standing by the roadside, the soldiers looked to be searching the vehicle. Shortly afterwards, a car pulled up.

What looked like a professional British Army officer to Stephen Travers appeared.

“Whether he got out of that car or whether I hadn’t noticed him before, I’m not sure. He was very much an authority figure and immediately the whole atmosphere changed. I remember his demeanor – very fit, active, good-looking and well-spoken.

“I remember admiring the ‘Action Man’ aspect; the combats he had on. I was a young fella myself, just 24. “When he arrived, things became very professional.”

That was reinforced by Brian McCoy, another member of the band.

“He nudged me with his elbow and told me not to worry. ‘This is British Army,’ he said. That was to comfort me. Brian was from the North and he was used to that kind of thing.

“I had been well-used to English accents because when I left school I went to London and worked as a trainee broker at Lloyds, so I was in no doubt but this was an upper-crust Englishman. He was also dressed differently than the UDR men. As soon as he arrived, the joking stopped.

“There was another man giving the orders until this British officer arrived and changed the orders. Initially, the UDR soldier Thomas Crozier was ordered to get our names and addresses.

“The British Army officer asked the UDR man in charge (I think he was Rodney McDowell) what Crozier was doing and was told he was taking the names and addresses. The army officer said: ‘No. I want the names and dates of birth.’”

The mood changed noticeably and the soldiers’ joking with the band stopped.

Suddenly there was a loud bang.

Two of the soldiers had been planting a bomb in the minibus. The bomb went off prematurely and the two men carrying the device, Harris Boyle and Wesley Somerville, were killed instantly. The blast ripped the bus in two. The explosion threw all the band members into the air.

The rest of the UDR soldiers opened fire on the band members lined up along the roadside with their hands on their heads. Submachine-gun and pistol bullets were flying everywhere. Dozens of spent cartridges littered the road.

Fran and Tony started to drag Stephen to safety but he collapsed and they could carry him no further. The UDR soldiers jumped down into the field in pursuit. Fran and Tony tried to flee.

“It was there [in the field] that the gunmen caught up with them,” Stephen remembers. “I heard them screaming, begging not to be killed. I can still hear them crying out. There was a long, loud burst of gunfire . . . and then silence.”

Stephen was badly wounded by a bullet in the thigh. Fellow guitarist Des McAlea was blown into a ditch by the bomb blast, away from the immediate kill zone, and relatively uninjured.

“I was shot in the right hip by what they call a ‘dum-dum’ bullet. On impact, the bullet fragments and does a lot of damage inside the body. It went up to my lung and exited under my left arm.”

One of the soldiers walked through the debris of the shattered vehicle, kicking the bodies and checking to see if anyone was alive.

“I heard him walking towards me. As he came closer, I decided I’d just stay where I was and pretend to be dead, face down in the dirt. What happens is that your instinct for survival takes over and it allows you to do things that you wouldn’t normally be brave enough to do.”

Stephen Travers stayed motionless as the soldier approached.

“Then somebody else shouted, ‘Come on! Those bastards are dead. I got them with dum-dums.’ That’s the first time I heard the term ‘dum-dums’. In fact, I thought that meant they were blanks.”

When the soldier checking the bodies turned and walked away and Stephen thought the place was clear, he eventually got up and walked around.

“I’d had a lot of internal bleeding and found it difficult to breathe because the bullet had punctured my lung.

“When I walked around you can’t imagine the scene. They’d pumped 22 bullets into Fran’s face. It was horrific.”

After Des McAlea had been blown over into the ditch, he hid and then made his way to Newry RUC Barracks.

Ambulances were called but the RUC and British Army were reluctant to go to the scene in case the bodies were booby-trapped.

“Eventually they got me to the hospital about 45 minutes later. I was taken to Daisy Hill Hospital in Newry and my faith in human nature returned once I woke up because the staff there were so good to me. I remember the doctors wanting to cut my jumper to get at the wound and me telling them not to – it was only new,” Stephen laughs.

“The RUC questioned me while I was on the operating table. They didn’t know who we were, that we were a band. I felt like I was being interrogated. They were asking me, ‘What are you doing up here?’ I said I was playing and they said, ‘Playing at what?’ They hadn’t a clue who we were.”

Even though he was in hospital, Stephen still feared that the immediate nightmare wasn’t over.

“Once I got off the critical list I started to worry in case, as a surviving eyewitness, I could be bumped off. They reluctantly agreed to transfer me to Dublin.”‘ He was taken to a nursing home in Elm Park. “‘I was as tough as old boots and fit, only 24 years old, so I was out in two or three weeks.

“‘I didn’t know for about a week that the lads had been killed. I suppose you block things out. You’re in denial.”

To him, the Miami was ‘just a showband’, playing to all sorts of audiences and in no way politically active.

Stephen Travers disapproves of violence from any quarter: “I have no time for violence. The Miami Showband were musicians, not political animals.”

So why does he think the band was targeted?

“The band was made up of people of different religions – Protestants, Catholics, Pagans and all,” Stephen smiles. “The one healing agent at the time for young Catholics and Protestants was entertainment. So if you could frame a prominent, well-known band like ours and make us appear like bombers, the healing function we had in bringing people together would have been discredited.

“We were the catalyst that brought people together. We were apolitical but, with hindsight, I see that we were overcoming sectarianism.”

• The Miami Showband Massacre: A Survivor’s Search for the Truth (Hodder Headline Ireland), by Stephen Travers and Neil Fetherstonhaugh.

This article first appeared on 27 September 2007 on the book’s publication.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures