25 October 2016

Tom Hayden RIP – An incalculable loss to the struggle for civil rights, justice and freedom

● Tom welcomes Bernie Sanders to Los Angeles in June 2015

I AM VERY SORRY to hear of the death on Sunday at the age of 76 in Santa Monica, California, of Tom Hayden, an incalculable loss to the struggle for civil rights, justice and freedom.

I first met Tom 40 years ago when he was visiting Ireland and had with him his young son, Troy. They stayed with me and my wife Sandra in Beechmount, in west Belfast, for several days, and ever since then we kept in touch with each other.

He was a fascinating person to be with and to listen to and learn from.

His involvement in the civil rights movement in the US is legendary: his was the voice of a new generation which opposed the war in Vietnam and espoused radical politics and challenged prejudice, discrimination and justice, both domestically and internationally.

He wrote several influential books on Ireland, including Irish Hunger (1997) and Irish on the Inside (2001). As a former California state senator, he passed legislation incorporating “The Great Hunger” into the public school curriculum used by 500,000 students, and co-authored California’s MacBride Principles on fair employment in the North of Ireland.

● The famous Cesar Chavez – co-founder of the National Farm Workers’ Association – with Tom in the 1970s 'an important mentor and friend to me’

He was an advisor to the US Commerce Secretary Charles Meissner during his economic mission to Ireland in 1997 and was a regular visitor to Ireland and to my home since.

My deepest condolences to his wife Barbara, son Liam, to Troy, his sister Vanessa and mother Jane.

Ten years ago, on the 25th anniversary of the H-Blocks Hunger Strike, I asked Tom to contribute an essay to a book I was editing. Here is the piece he wrote back then.

DEAD MEN LIVE

Tom Hayden, Irish-American social and political activist

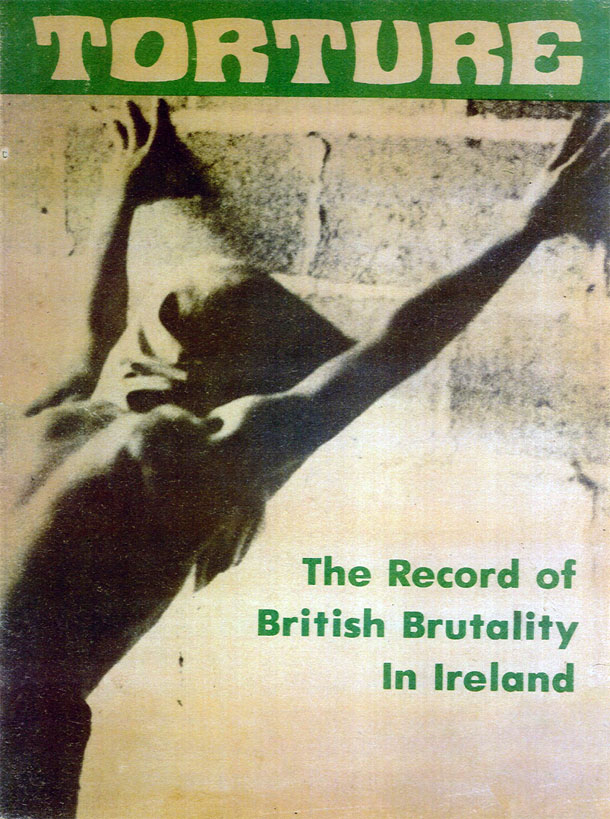

“The blame for this sorry story, if blame there be, must lie with those who, many years ago, decided that in emergency conditions in colonial-type situations we should abandon our legal, well-tried and highly-successful wartime interrogation methods and replace them by procedures which were secret, illegal, not morally justifiable, and alien . . .”

– Lord Gardiner’s minority report on British prisons, filed on Bloody Sunday, 1972

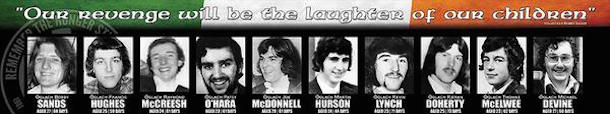

THOSE TEN DEAD MEN are alive in Irish consciousness, in the global human rights movement, in cages from Abu Ghraib to Kabul and Guantanamo, in a welcome corner of my mind. They endured the most, and their ghosts still thwart the morticians of oblivion.

As others have said, the election and death of Bobby Sands MP was the turning point that launched Sinn Féin’s electoral strategy and fostered the possibility of the Peace Process. Across the world, the Hunger Strikers today are honoured more than Margaret Thatcher.

In America, the Hunger Strikers broke the muzzle which the Irish-American establishment had placed on the voices of Irish republicans. US House Speaker Tip O’Neill could no longer prevent the 93-member House Ad Hoc Committee from holding hearings on human rights violations in the North. Sympathetic media coverage increased. Contributions to NORAID soared. Huge picket lines filled Fifth Avenue. The Massachusetts legislature “wholeheartedly” endorsed “the ultimate objectives of the IRA.”

Patricia Harty, now Editor of the respected Irish America magazine, was a young immigrant in San Francisco, living with two English roommates and working for an American company that supplied airline food. While she herself participated in demonstrations outside the British Consulate, her co-workers couldn’t get their heads around the Hunger Strike at all. They were, “sympathetic but horrified. Like, ‘How could they do that?’” However, she remembers, there was “awe, that these young men in the prime of their lives could do this”.

Looking back, she believes most of those people she worked with forgot the Hunger Strikes shortly after “but maybe, maybe they did learn something – that being Irish wasn’t just all jigs and reels on St Patrick’s Day”. The wheels of assimilation were set in reverse.

Some Irish-Americans could be counted upon to blame the Hunger Strikers themselves. In the centre of Irish Boston, for example, the Irish-born historian Pádraig O’Malley, whose name seemed to bloom with authenticity, attacked the Hunger Strikers for a primitive, degenerate nationalism. Stating openly what a majority may have privately believed, O’Malley wrote that the Irish were their own oppressors: “We need England. We need it to disguise the sordid and sad reality of our murderous designs on each other.” (Boston Globe, 6 May 1981, suggesting that O’Malley wrote these words on the very day Bobby Sands died.)

I was in west Belfast in 1976 about the time Bobby Sands was rearrested and taken to Castlereagh [Interrogation Centre]. I did not have the chance to meet him but, like millions of others, he and the other Hunger Strikers have continued to live in my consciousness. When I returned to Los Angeles, I joined many others in writing letters of solidarity to the Irish prisoners and picketing the British Embassy.

I began feeling like a stranger in my own land as I encountered the blank stares of my non-Irish friends (not to mention some of Irish ancestry, who seemed to feel “outed” by the Hunger Strikers.) I remember not being able to get their suffering out of my mind, not being able to purge a sense of guilt, not being able to avoid the tears in public when the devastating finish came.

Were these feelings born of romantic republicanism, morbid Catholicism, or a vicarious fascination with death? Of course, there was a long, historic – and officially discouraged – tradition of hunger strikes in Ireland, and of course the Republic itself was inspired by the martyrs of 1916.

And, yes, there was something Christ-like in the persona of Bobby Sands, just as there was in Che Guevera. I was influenced by all these things but most of all by admiration at the Hunger Strikers’ collective revolutionary will.

When I interviewed a survivor years later, Laurence McKeown, he showed no sign of desire for martyrdom. “We were captured soldiers, and so we used our bodies as the last weapons we had,” he simply said.

At least they did not die in vain, or invisibly, like many of the demonised across the planet. They bested the British, defeated oblivion, awakened a whole generation, but also contributed to a global movement for the human rights of political prisoners and families of the disappeared. That movement sometimes achieves surprising successes, as in Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay in recent years, where the memory of ghosts is stronger than amnesia.

Another reason the example of the Irish Hunger Strikers still resonates is because the Empire, however weakened, continues its cruelties. By “Empire” I mean the arrogant Anglosphere of the British and their grown and twisted children, the Americans. The dysfunctional family has joined together as the hated Multinational Coalition in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In his prison poem ‘Modern Times’, Bobby Sands foretold the present, “where the oil flows blackest, the street runs red”. And again he was prophetic in ‘The Torture Mill’, written about the H-Blocks:

They chop your neck, then walk your back

Spread-eagle you like pelt.

For private parts their special arts

Are sickeningly felt.

They squeeze them tight with no respite

Till a man cries for the womb

That gave him birth to this cruel earth

And torture of that room.

There is a straight line from tiger cages in Vietnam, to broken bones in Palestine, to death squads in Chile, to the concertina wire and renditions in Afghanistan and Iraq, from the Brits who disguised themselves as Arabs in places like Aden to carry out the theories of [British Army counter-insurgency specialist] Frank Kitson, and the neo-conservatives of the Reagan-Thatcher era to the imperial fantasists of today.

Just as the British carefully designed techniques in the 1970s to circumvent the technical definition of torture, pleased instead to be condemned only for “inhuman and degrading treatment”, so they and the Americans mask themselves in the same disguise today.

Gentlemanly authors of torture-by-another-name, they use their Oxford and Ivy League educations – and in some cases their medical school training – to inflict torments that neatly evade the legal prohibitions of torture. Pain, for example, if it is to be prohibited, must be of “an intensity akin to that which accompanies serious physical injury such as death or organ failure”. Mental pain, to be considered torture, must leave “lasting psychological harm”, not simply suffering at the moment of infliction.

Such methods, originating in the British Empire, tested on Irish prisoners, now are unleashed in the covert war on terrorism as “Counter Resistance Techniques”:-

- Hoods.

- Standing on toes for hours.

- Blinding light.

- Forced nakedness.

- Threats of castration.

- Beatings.

- Waterboarding.

All the disciplining gifts of Anglo civilisation to the lesser breeds. And always accompanied by innuendo and slur. The prisoners are savage, filthy, Blanket Men, ragheads, beyond redemption.

The occasional lapses into [impermissible] torture, as opposed to [permissible] interrogation techniques, always are due to the store of bad apples kept on hand for blaming. After seven official investigations by the Pentagon, none fix blame on civilian decision-makers (New York Times, 24 April 2004.) In the British case, both Tony Blair and the Tories are “united in ascribing the abuses in Basra to a tiny minority of British troops” (New York Times, 20 January 2005).

This has been a colonialism enacted with scarcely-concealed religious fervour. It was Robert Jones University in North Carolina that bestowed a divinity degree on the Reverend Ian Paisley. Murderous loyalists like Kenny McClinton belonged to the evangelical Prison Fellowship, a global network including American Watergate felon Charles Colson (according to God And The Gun by Martin Dillon, Orion, 1998).

In the Iraq crusade, Protestant evangelicals like Franklin Graham, son of Billy Graham, condemn Islam as a “wicked” religion and speak at the President’s prayer breakfasts. A chaplain critical of the rise of evangelical Christianity among the US military’s chaplains is forced to resign, while the Muslim-hating General William Boykin becomes the Pentagon’s point man for intelligence. The soldier convicted of sexual humiliation at Abu Ghraib sought clemency on the grounds that he distributed Bibles to Iraqi children. When the number of Christian missionaries in Muslim countries has quadrupled in the wake of the first Gulf War, have the Crusades not returned, at least covertly?

At the time of writing, there are 17,000 prisoners being held in Iraq, mostly on “suspicion”, charged in the Baghdad version of Diplock courts – 17,000 Bobby Sands.

The folly of empire is evident only in retrospect.

Do Brits today really believe that denying the Hunger Strikers political status was important enough to justify their death by starvation?

Do the Americans really believe that the tiger cages of South Vietnam were effective in preventing communist-led revolution?

Are they ever asked to reflect on their behaviour, or apologise? The answer, of course, is no.

But, before we lose heart, it always must be remembered that the authorities go to their extremes of obfuscation because they fear public opinion and the growing reach of human rights laws that have been erected largely through the sacrifices of political prisoners.

Somehow, Bobby Sands knew this, had a universal heart, knew that the human spirit could not be tortured into silence. He wrote of “flowers in the dark” or “bluebells” lifting their heads, just as the hounded African-American artist Tupac Shakur wrote of “roses that grow from concrete”.

A remarkable quality of Bobby Sands was the ability to write poetry on toilet paper, to smuggle intimate thoughts from the bowels of the self to the published page without computer or yellow pad.

He was a guerrilla poet.

He properly condemned a world where journalists write “not a single jot of beauty tortured sore” and “poets are no more”. But he resurrected a profound counter-tradition, where the needs of the soul are asserted against hopelessness, by any means necessary. That is the only hope of prisoners around the world today, and the threat that the captors cannot suppress.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures