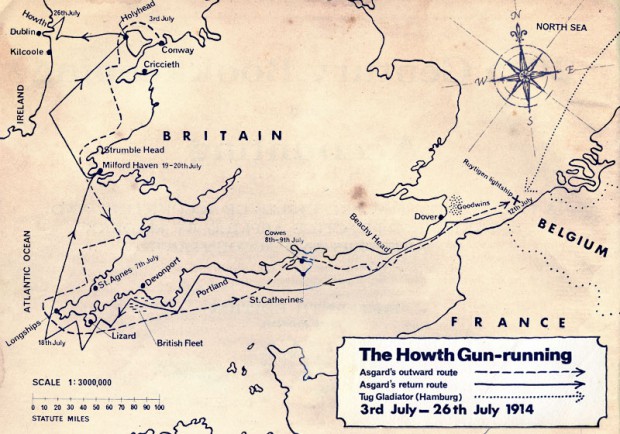

27 July 2014

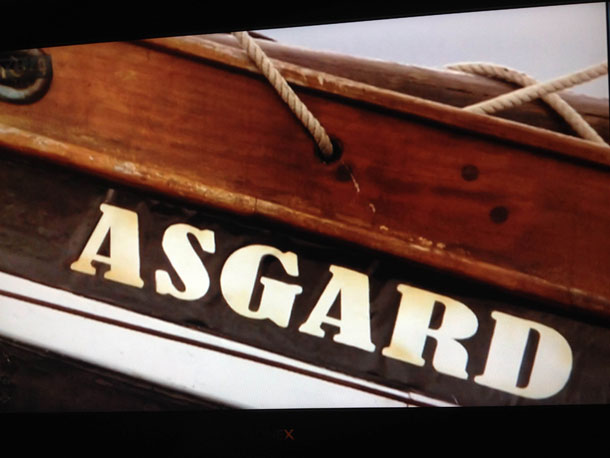

Diary of the Asgard

By Mary Spring Rice

Wednesday 1 July 1914

A long, hot and anxious journey over to Conway to join the yacht, starting with breakfast at 6:15am, motoring to Limerick for the 8:15, and crossing over by the 1:15 boat.

I was full of apprehensions that even now, at the eleventh hour, something might have upset all our carefully-laid schemes. Erskine met me at the station looking fearfully worried and tired. As we sat at dinner at the hotel before going on board he explained to me the various contretemps that had arisen: how badly the people at Conway had fitted out the yacht, how only one of the Donegal fishermen [Pat McGinley] hired by Mr Bigger as crew had come, and he had had to get a boy out of the Irish Volunteer Office as a stop-gap*. He was still hoping for the other fisherman to turn up and also expected the friend (whose name I had not been told but of whom 1 heard so much from Molly) to join him at Holyhead; and they were to start at 4am next morning, hoping to get to Holyhead that evening.

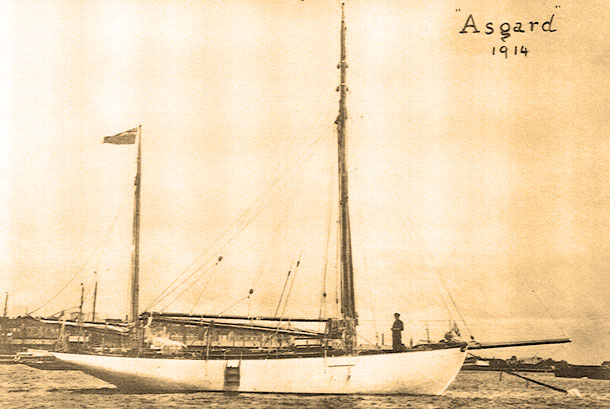

It was an exciting moment when I saw Asgard for the first time, her white paint showing up in the evening light. I had not expected anything nearly so smart but she looked fine and solid too and much broader in the beam than the Kelpie. Down below I was warmly greeted by poor Molly, who was trying to cope with a fearful scene of confusion. In the midst of ropes, tinned foods, marline, and clothes just unpacked, we laboured to get things straightened out before our early start. I wearily pulled my clothes out of canvas bags and holdalls and stowed them as best I could. There was a fearsome thunderstorm going on and it was breathlessly hot. However, I got to sleep at last and only half-woke at the 4am start.

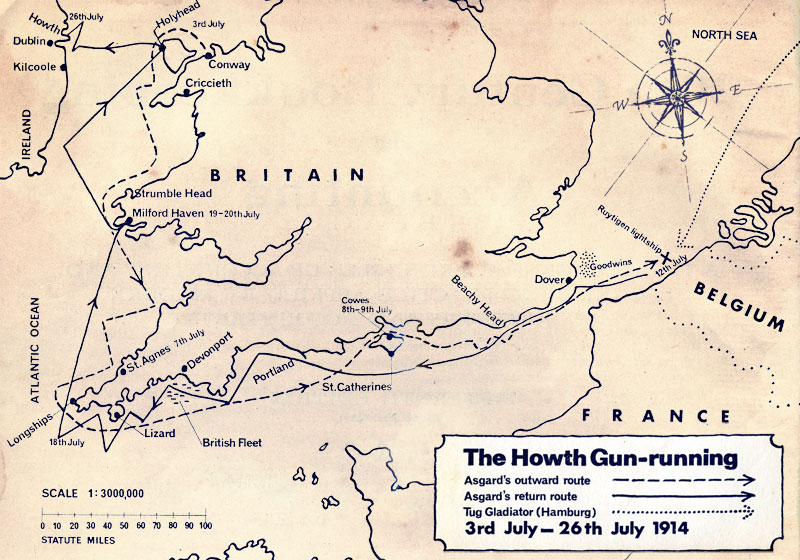

* Mrs Childers in a note describes him as “Mr John Dolan of Seamount Road, Malahide, who worked splendidly at every kind of hard task.” Mention should be made of an account of the Howth gun-running, as told by Mrs Childers and published by Máire Mhac an tSaoi, ‘Gunnaí Bheann Eadair’, in Comhar, Deireadh Fómhair. 1945, pp2-3.

Thursday 2 July 1914

There was too much noise on deck to sleep long, and Molly and I struggled into our clothes pretty early. The glass had dropped very low and a thick mist had come on. In fact, it looked like dirty weather outside and Erskine hesitated about going on.

Dolan, the Irish Volunteer Office boy, though full of silent Sinn Féin enthusiasm, did not know one end of a rope from another. However, he was very obliging about washing up and getting food ready.

Erskine and Molly were both dead tired and I longed for the advent of the friend and the second fisherman.

Finally, as the weather grew thicker and worse, we settled to turn back and wait for the tide next morning to get over the bar, and wire to the friend to come to Deganwy (close to which we were now lying), instead of to Holyhead. I was aching to be really off but it was rather a mercy to be in harbour for a day to get things straightened up a bit and I persuaded Molly to let me take a hand in the cooking. One bright spot in the day was that the second fisherman turned up (Duggan by name) and proved to be very nice.

Friday 3 July 1914

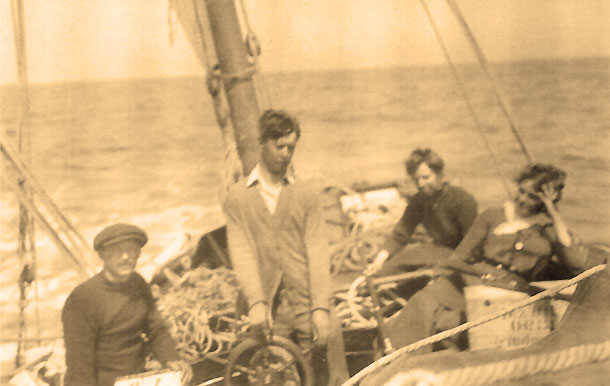

• Molly Childers and Mary Spring Rice aboard the Asgard

Up early for I was to go ashore to bring Mr Gordon [Shephard], the friend, whose name was at last disclosed, off to the Aagard as soon as possible, going up to the Junction to meet him for fear he should go on to Llandudno by mistake and not change for Deganwy.

His train was due there at 9:17 and we were due to sail at 9:30 to get over the bar. I got to the Junction and looked anxiously along the train from Holyhead. It was full of depressed holidaymakers (it was still pouring) and dull old men who looked up indignantly from their papers, as 1 looked into carriage after carriage in vain. I went back drearily to Deganwy, thinking we were stuck again, and was just going off in the dinghy when Mr Gordon suddenly appeared. He had apparently spent a somewhat depressing night in a railway waiting room. However, there he was, and in an extraordinarily short time we threw his luggage on board and were off. Just over the bar in time, thank Heaven, but it was a near thing. Really started! I could hardly believe it.

I only regretted not having written to Conor to tell him of our starting so late. How he would ramp round at Cowes! I thought of him storming round and talking to the Lord knows who, with de Montmorency arriving as an additional danger.

It was a headwind and it fell very light so we spent most of the afternoon beating about the bay. I, however, was so pleased to be actually started and not to be ill (it was like a mill pond), that I felt fairly indifferent as to the rate or direction in which we were travelling.

Saturday 4 July 1914

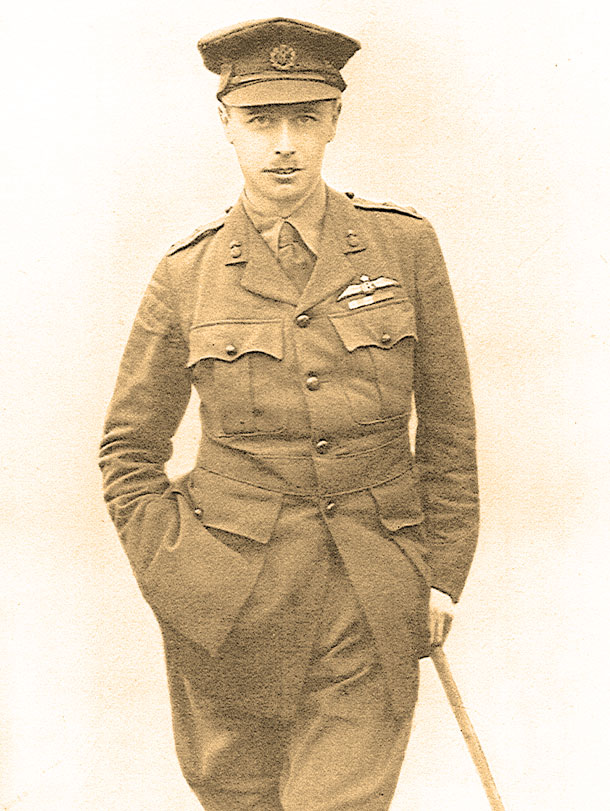

• Gordon Shephard and Erskine Childers on the Asgard

It was distinctly a fresh breeze when I woke up and got what I thought was very rough indeed as the day went on. Cooking buttered eggs in the fo’castle seemed impossible but was not so bad when it came to the point.

Pat has got to be rather good at cherishing the Primus, so I leave that to him. All the same, I was glad to escape from the fo’castle on to the deck, where I stayed most of the day, my lunch and tea alike consisting of small pieces of captain biscuits munched in the cockpit.

Erskine, Molly and I all felt (and some of us were) extremely ill. Poor Molly had to lie down in her cabin, so was much the worst off. I felt just able to survive while I stayed on deck, and all the afternoon the wind rose. It was SE and there was lots of it, and a very choppy short sea into which the Asgard drove her bows.

I curled up in an unhappy heap on the cockpit floor, cold and miserable, in a leaky oilskin (oh, uncle, it was Dunhills), feeling dimly that Mr Gordon, who was steering, would much have preferred me out of the way. Also that the Asgard now looked extremely small, a mere cockleshell on the waves, and I wondered how long it would go on like this. Mr Gordon every now and again assured me it was not really rough. However, late in the evening, he and Erskine determined to make a board in towards Fishguard, and put in there if it got very bad, and my drooping spirits revived though it was still horribly rough when I crept into my bunk.

Sunday 5 July 1914

Much calmer, thank Heaven, but I still felt fairly ill though I managed to get to the fo'castle for a few minutes and started Pat to boil the eggs, timing them.

We all felt on the mend this morning, and it was a comfort to see Erskine able to eat something again, and Molly able to come on deck. E and Mr Gordon lamented all day (and indeed for many days to come) over that board in towards Fishguard and the time lost thereby. E regarded it as a neglect of duty for the sake of comfort.

All day the wind headed us and we spent the afternoon trying to get round Strumble Head against a strong wind and tide, and racing a Brixham trawler which eventually walked right away from us, to our disgust, we having been ahead for ages.

It was a perfect afternoon and one began to feel like settling down. Erskine lost the look of tense anxiety which he had when we started, though still greatly preoccupied with the problems ahead (times and seasons, transhipping, etc) and that afternoon we assembled in the cockpit, the men being safely below, while he unfolded to us the landing scheme.

I had, of course, been aching to know it for weeks and was half appalled at the daringness of it, and half-delighted at the coup if it really came off. But there seemed many a slip - Howth so near Dublin, trams, telephone, soldiers, coastguards, and cruisers. How we discussed all these possibilities as we sat round after supper that evening and many evenings to come!

Molly and I decided it was altogether too hot to sleep with the cabin door shut and as it opened straight into the hatch and companion, it meant rather sleeping in public. The theory was that one put out the light and then no one could see in but as it got light, about 4am, that rather broke down. However, I don't really mind, compared to sleeping in a tug. I can hear Elizabeth saying how like me!

Monday 6 July 1914

• Erskine Childers

Got up to find us still struggling to get past the Smalls Lighthouse, no wind and a great swell, but I felt much better than yesterday, although dressing was an exhausting business, and I recuperated for half an hour on deck before descending into the fo’castle to see to breakfast.

All efforts to rouse Mr Gordon proved in vain until a tin of Golden Syrup was got out. On hearing this he shut the saloon door (he had the passage bunk) and appeared in a surprisingly short time.

One of my chief duties, I found, was keeping the food hot for the latecomers and, as I sat close to the fo’castle door and the stove was just inside, it was quite handy.

Erskine and Molly went up on deck when Mr Gordon, lured by the Golden Syrup, came in to his breakfast. I was amused to see how thoroughly comfortable he made himself, quite à la Leonard, curled up on the seat with the Golden Syrup tin propped up beside him.

I went up on deck and shortly afterwards heard a shriek from Molly: “He's pouring all the Golden Syrup onto the bunk!” I peered down. Evidently he had gone to sleep with it propped up beside him and it had overflowed. However, there were three more tins on board.

We mopped up the bunk and went up to study the wind, which had fallen very light. There was a great swell. We rolled about desperately and still were not past the Smalls. We all felt rather despairing and Mr Gordon, who is a sort of cold water douche, in case any of us did get too optimistic, made an elaborate calculation to prove that we should certainly get to the rendezvous at the Ruytigen too late.

We only seemed to have averaged about 2 knots since we left Conway. At last we got up nearer to the Smalls, and Erskine decided to go inside through the passage with a bubbling tide race and horrible-looking rocks. Altogether it looked a wicked place. However, of course, one felt a sublime confidence in Erskine’s steering and we got through alright. Then the wind got up and we were soon humming along. In fact, by teatime it was a problem to keep anything on the table.

We had now left the Welsh coast and thankful we were to see the last of it. I never knew Wales went on so long. We were making for Cornwall along the mouth of the Bristol Channel with a big Atlantic swell rolling in and still beating with a wind about sou’ sou’ west.

To bed with the prospect of a very rough night, Mr Gordon having assured me that when we went about I should certainly be shot out of my bunk, so I moved the water-can out of the way, thinking how painful it would be to fall on.

Undressing was a slow and painful process but, once in, I slept the sleep of the just and awoke to find a glorious morning with the sun shining on the purple coast and white cliffs of Cornwall.

Tuesday 7 July 1914

• Pat McGinley

The half-hour on deck before breakfast is very joyful after the stuffiness of dressing with the cabin door shut. I do as much dressing as possible with it open but there were moments when it had to be shut and then the fog.

When I came up on deck this morning and felt the fresh sunshine and delicious morning air, I felt life was really very good; and there was Cornwall quite near – it seemed only just round the corner to Cowes. I found Erskine steering and poring over a chart. “We are just off St Agnes’s Head,” he said. He has given himself rather a nasty finger by running something into it.

All that day we beat along the coast of Cornwall. We had some thought of putting into St Ives, which looked most attractive in the sunlight, and waiting for the afternoon tide, but this was sternly discouraged by Erskine – firmly resolved that not a moment of time that he could help should be wasted on the way to the rendezvous.

I believe he was quite right, though Mr Gordon had got as far as planning out his lunch ashore, and I was just meditating if it would take the shine out of my Cowes shore clothes to wear them when Erskine had appeared and said firmly we should push on even if we only made a few yards against the tide.

Later on, Pat got a hit on the head from a block which gave him a horrible cut just over his eye. Molly dressed it in the saloon while I held the things for her; it was an awful job for there was a good sea on round Land’s End and everything was falling about in all directions.

It was a great moment when we rounded the Longships still beating against a stiff southerly wind, and very misty. Still, this was the moment we had prayed for, when we thought of the fair wind up-channel, through all our long weary beat down the Welsh coast. And now it was NOT a fair wind till we got past the Lizard.

We had one (to me) rather awful moment when, as we scudded along through the misty twilight, we suddenly heard a deep fog-bell booming on the port side. “Damn it,” said Mr Gordon at the wheel (and he never uses language as a rule) ‘The Runnelstone Buoy’. It was hard to make out the position of the Buoy in the mist and it sounded alarmingly near. However, we went about and presently Molly’s quick eyes discovered it.

I had contemplated for a few moments how long the Asgard would live on the Runnelstone Rocks and what it would feel like when she broke up, and then was relieved to hear the fog-bell growing fainter in the distance.

At long last, round the Lizard and a fair wind up-channel. I was much absorbed in getting supper ready as when I went below I found it was a quarter to 8, and Pat being ill I had to do all the work myself. There were tins to be hunted for in the lockers, potatoes to be cooked, everything to be found, and the table set with the boat rolling about in a big swell all the time.

Poor Pat must have had a chastened time pitching about in his small, stuffy bunk with his cut-open head. I stopped my cooking operations to put a wet bandage round his head (one of the parents’ handkerchiefs just came in handy; mine would never have gone round). As I fell about the fo’castle searching for everything, I made up my mind I would know where things were myself in future.

Molly took a watch with Mr Gordon tonight as Pat was hors de combat, and I got up at two and made them hot drinks for the change of the watch. I found I went to sleep again quite easily, and slept on shamefully late on Wednesday morning and actually felt hungry for breakfast.

Wednesday 8 July 1914

Mr Gordon wasn’t satisfied until we had set every stitch of canvas on the boat (just like Leonard and Conor), however we had to take down the spinnaker going through Portland Race.

I should, personally, have felt happier without the topsail, however we were going against time as usual and had to push on. Erskine steered her wonderfully through the choppy sea though it was rather hard on his injured hand. Now at 7pm we are scudding along with the wind dead aft, doing about 7 or 8 knots with a blue sky and a still breeze, hoping to make the Needles tonight.

I frankly confess I am looking forward immensely to being in harbour again. In fact, we have talked of the joys of Cowes and of the meals we are going to eat ashore for the last 3 days.

All the same, I was rather afraid to face Conor, who had been there for days, and was probably in a state of wild impatience. I hadn’t liked to write from Conway that we were starting till we were actually off and then there was not time. But I had many misgivings as we approached Cowes.

We got in at 1am. It was quite beautiful passing through the searchlights with the water all gleaming and rippling under a sort of unearthly glow. While the men stowed the sails and settled things up generally, I went down hastily to make hot drinks and so to bed at 2am.

Thursday 9 July 1914

• Darrell Figgis

We had the best intentions of getting up early but when I turned over in my bunk it was already 8:30. I struggled hastily into more or less clean clothes and managed to get breakfast about 9 o’clock.

There was a lot to do (repairs to sails, etc) for some of the gear had gone in that rough weather off the Welsh coast. Besides, we had the Hamburg business to settle. Hardly had we finished our last mouthful when a loud “Asgard ahoy!” was heard, and I dashed up on deck to be received with a torrent of abuse from Conor. ‘Why were we so late? Why had we never written?’ He had spent all his money waiting for us and de Montmorency had gone back to Dublin.*

I found to my horror that Conor had been sending a series of wild telegrams to Mrs Green via de Montmorency, asking her where we were. If all Cowes – and Dublin, not to say the Castle – do not know of our expedition, it is a miracle. The only hope is the Government are fairly stupid.

I tried my best to calm Conor down and finally he departed somewhat soothed. Meanwhile, Mr Gordon had been struggling into his shore clothes in the saloon and finally appeared resplendent in blue serge (I should hardly have known him) and we went ashore. I found I could hardly stand so I tottered to a lamp-post and clung to it regardless of Molly’s protests. It might be quite true as she said that people would think I was drunk but if I stopped clinging to it I should certainly fall down, which would be worse. So I clung till I felt a little more secure but all that day I felt rather dizzy and fairly reeled along the streets of Cowes.

We spent rather a harassing morning, getting our letters and sending telegrams to Figgis at Hamburg with final directions about our rendezvous and trans-shipment. We must have looked a quaint party, Molly and Erskine and I driving around Cowes whispering to each other, sending prepaid wires and anxiously returning to the post office for the answers.

I was rather worried at not having heard from father and did not know where to tell him to write, our ports of call were so uncertain, and I was afraid he would worry if he didn’t know our movements.

Lunch at the Royal Marine Hotel, that meal which we had greedily discussed for days beforehand, was very large and excellent. I had made up my mind three days ago to have an iced lemon squash and had thought of it ever since.

After lunch, more shopping till I could hardly drag one leg after another. Finally I managed to get my Cowes yachting cap just before the shops shut and we all met for dinner; another large meal at the hotel. I have over-eaten shockingly today and spent all my money, not on meals (which Erskine insisted on paying for) but on the yachting cap and on various luxuries in the way of extra pots and pans for the fo’castle. I got a friendly grocer to cash a cheque, spent all that, then I met Mr Gordon and borrowed two shillings from him and finally landed up without one penny at the hotel.

As we sat at dinner we espied through the window Conor, Dermod Coffey and Kitty landing. This must be the olive branch we thought and so it was. They had coffee at the hotel with us and then took us on board to see the beauties of the Kelpie.

It was a perfect evening and all was peace and quietness, Conor having quite calmed down. Details about trans-shipment were settled. Each boat was to take half the cargo and Conor was to sail on the morning tide. We could not get off till the afternoon as the sail maker didn’t finish on board the Asgard. We were to try and meet at Dover but not wait there beyond 8pm Saturday.

While the others were talking plans I gathered from Kitty something of the course of events before we arrived at Cowes. It was a great blow after the pictures we had been drawing of de Montmorency as the bold buccaneer to find that he had left the Kelpie because the cabin clock ticked too loud and after a night at the hotel had gone back to Dublin. It was probably fortunate he went back in view of the discomforts he would have come in for later on, but it was a sad blow to all our romantic theories about him.

Kitty explained Conor’s financial difficulties by their having bought such a lot of cream, which was apparently very dear at Cowes. At any rate we parted in a much more friendly way than we had met in the morning and that was something.

* For Hervey de Montmorency’s eventful career, see his autobiography, Sword and Stirrup, London 1936.

Friday 10 July 1914

Up early and breakfast before 8 to get ashore and do a couple more things as we may not have time to put in at Dover.

Great calculations all the time as to space. How I hope Molly and I won’t have to leave in the tug. The space certainly does look very small for all we shall have to put in but she and I don’t take much room to sleep.

We spent the rest of the morning clearing the lockers in the bunks to make room for guns, storing a lot of the provisions under the fo’castle floor, a plan which had its drawbacks when you wanted to get out something on a very rough day. I had a field day in the fo’castle so as to try and use the space to the best advantage.

At slack water in the afternoon we got up the anchor and were off again, beating up the Solent against a headwind and as usual against time. The wind got up a good bit and cooking supper was not an easy job, or going to bed. Mr Gordon insisted on setting the topsail, much to Molly’s disgust, and she went to bed protesting how much more comfortable we should have been without it. I rather agreed with her at the time as I struggled into my bunk and sighed that all men were alike about setting topsails on all possible occasions, but we sped along so perhaps it was as well.

Saturday 11 July 1914

• Pat McGinley, Gordon Shephard, Mary Spring Rice and Molly Childers

Much calmer, which made getting up and cooking more pleasant but it was a bad look-out for getting to Dover. All day long we had light headwinds and 8pm found us still struggling to get round Beachy Head.

A roasting hot day even on the sea, and my pink sunbonnet was my one joy. We had laid in a lot of fruit and vegetables at Cowes and were living much more luxuriously than before. Mr Gordon had great ideas of being as comfortable as possible and he and Molly had bought lavishly.

But it was a depressing day full of doubts and anxieties.

Sunday 12 July 1914

• Connor O'Brien

The day of the meeting, should we ever get there?

It certainly didn’t look like it when I came up on deck to find Erskine steering in a calm sea with a light breeze ruffling the water and fog just lifting and letting the sun through. A heavenly summer morning –– if one had not gun-running appointments at the Ruytigen Lightship, 45 miles away, at 12 noon to make one pray for a wind.

I had slept like a top, thanks to the calm night and was really hungry for breakfast.

But we all felt rather anxious and made calculations about the fair tide after Dover and speculated as to how long the tug would wait if we were late and as to what directions there might be in Figgis’s letter to Dover which we had not time to call for. Then we all fell to work doing the final cleaning of the saloon and cabin for the guns.

This meant cutting up the two saloon bunks and Molly, Pat and Mr Gordon were soon hard at work chopping and sawing. We were keeping right inshore as the tide was still against us, and when I came on deck after looking through the store of eggs (a very important part of the supplies), I saw Folkestone beach within a stone’s throw, full of the ‘smart set’ parading their best clothes in the brilliant sunshine, while on the starboard side lay 4 or 5 warships with their bells ringing for church.

The Asgard slipped along between the shore and the ships, her crew making an awful noise chopping and sawing, which they devoutedly hoped was not heard on either side. Then it fell a flat calm; however, the tide had turned now and we drifted along.

We were discussing whether we should take the saloon table to pieces (which Molly inclined to; Mr Gordon being strongly for keeping it as it was and packing guns under it) when suddenly there was a joyful shout from Duggan at the wheel, “A west wind”, and sure enough a breeze had sprung up.

Hastily the spinnaker was set on the bowsprit, then the wind shifted and it was set on the boom, and it was 2:30 by the time we sat down to lunch.

Meanwhile, the fog had come on fairly thick and it was becoming a difficult question how we should make out the Ruytigen. Erskine had told the men our objective and Duggan, at any rate, was as excited as we were.

We heard the East Goodwin fog signal booming away on our port side and then we listened and listened for the Sandettie fog signal, which was pretty well on the course for the Ruytigen, and Erskine and Mr Gordon disputed about how much to allow for the tide sweeping us north.

It was an anxious afternoon, even Mr Gordon gave up his after-lunch sleep, and we all stayed on deck, straining through the sultry summer air to hear the faint boom of the signal –– past the line of the Sandettie now and still no sound. It as a question now if we should find the Ruytigen before the tide turned.

At last, Molly’s quick eyes sighted a buoy, then a lightship –– the Ruytigen at last.

We had come just right, certainly a triumph of navigation but no sign of the Kelpie or the tug. I thought gloomily of all the possibilities –– some change of plan in the letter for which we had not called at Dover; Conor having gone off somewhere in the tug in despair at our being late, or Conor still at Dover and cursing us for not calling there.

Then a sail on the horizon. “Conor!” cried everyone anxiously, and we all strained to see. I, of course, could not distinguish the boat, so I kept watching Molly’s face, which at last fell dismally; it was only a fishing smack and despair settled down on us, fearing we should not find him or the tug before night.

A cry from Molly revived our drooping spirits: “Conor and the tug. Do you see? A steamer and a yacht mixed up – lying close to one another now the tug is coming towards us.”

A few moments of breathless excitement, then there was no doubt: the tug was bearing straight down on us.

I rushed down to the cabin to shove away my last remains of clothes and get the place clear. I had felt it was unlucky to do this till we were sure of the tug, superstitious as always.

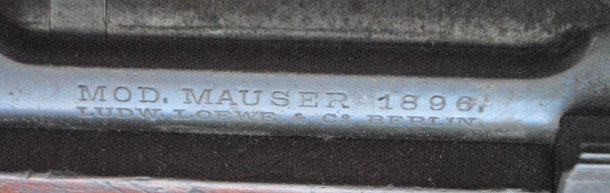

We hastily hauled bags of clothes and mattresses and stowed them aft of the mizzen. As the tug came up, Darrell Figgis called from her deck that Conor had taken 600 rifles and 20,000 rounds of ammunition. “He’s left you 900 and 29,000 rounds,” he shouted. We looked at each other. Could we even take them? We had only counted on 750 and they looked enormous, each thickly done up in straw.

However, before we could say ‘knife’ we were all at work unloading. It was a perfect night, quite calm.

The tug looked black and huge alongside us. Her deck was full of German sailors who jabbered away and looked curiously at us as they passed down the big canvas bales to Pat and Duggan on our deck.

I found myself in the saloon with Mr Gordon, Pat passing us down rifles through the skylight, and we packing them in, butts at the end and barrels in the centre, as fast as we could. They came in bales of ten and we counted them as we stowed them: “8, 9, 10; steady a minute, Pat, till I stow this one.” Inside the cabin, Erskine and Molly were doing the same thing. 40 went into the port bunk in the saloon. Should we ever get them all in? “We’ll have to take the straw off and pack them singly if we’re ever to take 900,” said Mr Gordon, so we shouted up to take the straw off.

It was fearfully hot work. They were fairly heavy and thick with grease, which made them horrible to handle. Gradually, however, the pile grew and presently the saloon was half full, level with the table, and we went up on deck to help strip straw off as they could hardly hand them down fast enough. Then when we had undone a certain number below again to pack them in.

So it went on through the night. Still, bale after bale of rifles were passed down from the tug, and every now and again we shouted to the German crew to know how many more were still to come. And the saloon got full, and the cabin and the passage, and then we began to put on another layer, and to pile them at the foot of the companion hatch.

Meanwhile, the ammunition had been coming down in fearfully heavy boxes, which were stowed with infinite labour aft under the cockpit, a very difficult place to get at, at the foot of the companion, in the sail lockers, and a couple in the fo’castle.

Erskine was very keen to take all the ammunition we possibly could and certainly it seemed rather a sin to leave it to be put overboard by the tug, and aboard it all came somehow. Several boxes were left on the deck till we could make room to stow them. Personally, I felt rather nervous as to the effect this tremendous extra weight would have on the yacht in bad weather but Erskine’s one thought was to take everything.

As we toiled away I heard them saying we had drifted right down near the Ruytigen. The people there must have wondered what on earth we were doing but there was no time to alter our position, only try to finish it before it got light, and a faint glimmer of dawn was beginning to show as we stowed away feverishly to get them in.

Molly put pieces of chocolate literally into our mouths as we worked and that kept us going, till, about 2am, the last box was heaved on to the deck and the last rifle shoved down the companion, and the captain of the tug came on board to have a drink and consult where he would tow us to.

While Mr Gordon entertained him in his best German in what was left of the saloon, I collected the letters I had been accumulating to post since Cowes, and gave them to Darrel Figgis, charging him to post them at Dover or some port so as not to arouse suspicion, as even father might have thought it odd if I had posted him a letter in London. I found out afterwards that Figgis had posted them at Hendon, of all unlikely places for a person in a yacht to call at.

Oh, how tired we all were! I tumbled into the fo’castle, crawling over the guns in the saloon to get to it, and got the kettle on for hot drinks while the men were fixing the tow ropes. Down they came then and we all drank cocoa and beef-tea and then shifted down the mattresses and bags of clothes which had been stowed aft of the mizzen, and lumped them down on the guns anyhow (we were too tired to settle them properly) and lay down on them just as the grey light of the dawn was breaking. I remember thinking how absurd it was to go to bed in daylight and then went off into a dead sleep.

Monday 13 July 1914

• The Gladiator waits for the Asgard at Roetigen Lightship. Darrell Figgis (right)

Shouts from the tug roused me and for a minute I lay and wondered what had happened, we were going so unnaturally fast. Then I remembered we were being towed and roused myself to go on deck.

We were going about 10 knots through a fortunately calm sea in a thick fog, very low in the water, the deck covered with boxes labelled “Patronen fur Handfeuerwaffen: Hamburg” littered with straw, and generally looking about as disreputable as we could. The whole thing seemed like a dream of the night. Had I really spent the night handing down and stowing rifles? However, down below there was the solid reality –– saloon cabin and passage were all built up 2 and a half feet high with guns, and there was no illusion about the bruises one got as one crawled about on them.

The tug was to cast us off at Dover and by the time that operation was finished and the men free to come down, I had breakfast ready. The sun was beginning to clear away the fog into a lovely summer day and as we squatted cross-legged at breakfast, trying to be used to the camp attitude (the guns now being built up level with the table), we all felt a tremendous sense of relief.

At any rate, we had kept the appointment, had got the guns on board, and were started on the return journey, though the risks of discovery were now increased tenfold and the excitement proportionately greater.

There was still a good deal to be done stowing properly some of the guns that had just been shoved in anyhow by the companion in the haste to be off before dawn and then they had all to be covered with sailcloths and mattresses and the clothes and rugs sorted out again to their rightful owners. Even working all morning we hadn’t got things really straight by lunchtime but we were all tired and very dirty again; our hands covered with gun grease and filth.

A stiff breeze sprang up and Erskine decided to throw over the three boxes of ammunition left on deck as she was so low in the water and there seemed no more space below. Every corner was filled and several boxes had gone into the fo’castle, which was already crowded with stores. I specially hated them there, having a vague fear if the oil stove flared up, the ammunition might blow up and burn us all.

Over the three went, and Erskine bitterly repented it next day as things got straightened out and he thought he might have managed to stow them but it was too much of a giveaway to leave them lying on the deck. Besides, the drawback of having them weigh so high up in the boat, and really below it was a case of ‘no room to live’. So Molly and I were both rather relieved when they disappeared into the water.

The rest of the day was slack. We got a good breeze in the afternoon and lay about on the deck half-asleep except for one alarm passing a lot of warships near Folkestone when one of them began to fire a number of shots as we came up, our guilty consciences thinking it might be a signal to stop.

We passed quite close to our friend the Gladiator (the tug) during the afternoon, which caused a momentary excitement.

A beautiful night with a calm sea and a glorious moon and I should have been tempted to stay on deck,but, literally, I could not keep my eyes open and found my bed on top of the guns extraordinarily comfortable.

Tuesday 14 July 1914

I suppose one will get used to moving about on one’s hands and knees and the saloon is quite comfortable to squat in with a cushion at one’s back. But if it is rough I wonder what it will be like trying to get about it.

More work this morning, shifting some of the guns and hauling up the mattresses that cover them to dry on deck. Molly produced two splendid waterproof sheets which were tucked over those most likely to get wet at the foot of the companion.

Also we sorted provisions, etc, in those lockers which were still getatable and now things really looked ship-shape but it is terribly easy to lose one’s possessions in the cabin; they drop between the mattresses into the rifles and disappear. There will be a lot of hairpins found among them when they are unloaded.

Off Beachy Head about 7am and a fair wind which, alas, shifted to the beam, and then to a headwind by lunchtime and dropped very light.

Some of the paint on the yacht’s side, which had been scraped off by the tug, was made good this morning and, outwardly, she looks quite like a yacht again now.

How Erskine’s sore finger has survived Sunday night I can’t think but it really does look a bit better today, though it was very sore-looking yesterday. It is a great job for Molly dressing it in rough weather but she managed to accomplish it. I though she would be half-dead after Sunday but her spirit carries her through, though the difficulties of getting about for her now are, of course, enormous.

The odd thing about this sort of life is that one spends such a lot of time cleaning up and yet one is always dirty. Crawling is not good for the clothes, or gun grease for the hands, and doing one’s hair squatting like a Red Indian is rather a job.

One has to turn the mattress right back off the guns in our cabin to be able to turn down the basin, so that one only does it when one really does feel too dirty to eat before washing.

The cabin door had to be fixed permanently open so we had an arrangement of a dishcloth which could be hung across as a curtain when one was dressing but it was too stuffy to keep it hung up at night and shut out the precious air that came down the companion.

The worst was on a wet night when Molly insisted on shutting the companion hatch, not so much for herself as to keep the guns dry, and then the stuffiness was awful.

Wednesday 15 July 1914

• Charles Duggan

A good breeze this morning and cooking the breakfast was difficult.

Everyone has now come to the conclusion that fried bacon is the best thing for breakfast so, unless it is almost impossible to keep the pan on the Primus, fried bacon it is. Also, the eggs which got wet in the fo’castle are beginning to get a bit musty for boiling. Fried eggs are very hard on rough days; they fly about the pan and get disintegrated.

Awfully late at breakfast, and Mr Gordon was shaving in the saloon while I, propped up against the ammunition box in the doorway, was shoving in the breakfast things and trying to prevent them getting all mixed up with the shaving apparatus as everything was shooting about the table.

We have got into a sort of routine now and it is surprising how fast the day passes.

I generally crawl into my clothes between 7:30 and 8 with sleepy remonstrances from Molly for disturbing her so early, and calls from Erskine as to when breakfast will be ready. He usually takes the second watch and is very hungry by 8 o’clock. So, washing is reserved for later and I crawl to the fo’castle.

Pat generally has the Primus going and if one has not to tie the pans on with string, and hold on with one hand while you do everything, breakfast doesn’t take very long.

I manage to get a sort of wash with Monkey soap out of a mug –– better than nothing. Then portions have to be kept hot for latecomers: Molly (for whom dressing is such an effort), or Erskine (who has something to do on deck, just as everything is on the table), and Mr Gordon (whose food has almost always to be kept hot; he generally sleeps till the rest are well settled at breakfast).

After breakfast I do a little washing behind the dishcloth in the cabin then, if fine, the mattresses and blankets are given an airing on deck and probably Molly wants the things collected (hot water, etc) for dressing Erskine’s hand.

Then peace till lunchtime and I sit in the cockpit and sew or read, or learn Irish from Duggan, or study where we are going on the chart.

Lunch is cold and only has to be laid out, and my labours don’t really begin again till after the tea, when I start to get ready supper. Of course, on wet, wild days one is kept busy trying to keep the guns tucked up and dry.

We had passed St Catherine’s in the night; the place full of steamers and sailing vessels and one of the latter all but ran us down last night.

I shivered in the cabin below, wondering what was going to happen. It seems to be quite amazing how anyone can steer clear of boats in a crowded place at night; it must be so hard to judge their distance and pace. I feel pretty happy when Erskine and Mr Gordon are steering but not at all with Duggan or Pat.

We spent a long time today making Portland Head, beating all the time with a stiff breeze and a choppy sea. I steered part of the morning and found it quite hard work, the wheel was so stiff.

Through Portland Race in the evening, just as I was cooking the dinner, and awfully rough. One didn’t venture to leave a pot on the stove without holding it. It was almost impossible to keep on one’s feet as the floor was, as usual, covered with oil and the boat pitching in all directions. As it was, part of the stew upset but I got such unmerited praise for having managed to cook at all that it was well worth the trouble. Pat was a great help; he will be quite a ship’s cook at the end.

A beautiful night with the moon but still rather a choppy sea and one couldn’t get to sleep early.

Thursday 16 July 1914

Again woke to find ourselves beating along West Bay.

A nice calm sea after yesterday was a great boon and we kept close in to the Devonshire coast, which was lovely, the colouring very like Ireland only warmer with more red showing in the rocks.

Off Dartmouth we had an exciting race with a Brixham trawler and beat her handsomely. We were in among a whole fleet of them and they looked very picturesque with their red-brown sails showing up against the brilliant coastline.

Mr Gordon had a brilliant idea of hailing a small fisher-boat as we passed and, for two shillings, we got a fine lot of pollock, bream and mackerel, and are all looking forward to fresh fish tonight after a course of sardines and tinned meat.

Six days at sea now and the bread locker is beginning to run very low and we are fearfully economical of water. Molly protests if I wash more than once a day but with grease from cooking, black from washing potatoes, and oil from the fo’castle, it becomes necessary sometimes.

The cargo below has curtailed the airspace considerably and one spent as much time as possible on deck. Mr Gordon says his bunk is too stuffy to sleep in and has taken to sleeping in the passage, and it is almost a gymnastic feat to get by without walking on him. How Molly manages to get about with her leg is a constant wonder to me. I find it quite hard enough.

The wind which had been lively all the afternoon fell very light about teatime (it was still dead ahead), and by dinnertime we were rolling about in a wet, misty calm with a horrid swell which just upset a whole dish of fried pollock, which I had cooked, onto the floor. Everyone had been looking forward to the fish for dinner so it was rather a disaster. I hastily cooked some more but it was rather short commons and the bread which I made did not bake well as the stove got cold mysteriously while it was in the oven. So, altogether, the cookery tonight was not much of a success though the company was very tolerant about it.

After dinner, a fresh breeze sprang up and we beat along past Devonport and, to my horror, got in among the [Royal Navy] fleet.

They seemed to be executing some night manoeuvres and were all round us with their great lights towering up; it would have been very picturesque if one had been looking on from a safe position onshore.

There was one awful moment when a destroyer came very near. I stood holding up the stern light on the starboard side, watching her getting nearer and nearer, with my heart in my mouth. Then, mercifully, at the last moment she changed her course and passed us by.

Then the big jib had to be shifted and the jib sheet got lost under the dinghy and Molly and I had to fish for it lying flat on the deck and wriggling under the dinghy. By the time we were clear of the fleet and all the alarms and excursions over, it was 1am and I was glad to get to bed.

Friday 17 July 1914

Horribly choppy this morning but the wind fell and it was nearly calm by midday.

I had a bath before lunch, the first I have had, which was heavenly. I did envy the men their morning bathe. I never seemed to have had time for it with cooking the breakfast.

We stood right to sea this morning and are now heading for the land in the bay, past the Lizard, we hope, and then it will be a dead beat up to the Longships.

A grey, gloomy-looking day but a calm sea for which mercy I am very duly thankful. But, alas, the wind is falling very light and heading up.

If we don’t get round the Longships by midnight we probably can’t make Milford Haven Sunday morning to land Mr Gordon, who is due back to London that day. We might land him on the north Cornish coast if we are too late to make Milford, but we still hope and make every inch we can against the everlasting headwinds. It’s a great pity he has to go as if we get bad weather we shall be rather shorthanded without him.

It was a grey misty night and I sat on deck, straining to see the lights of the Wolf and Longships looming out of the darkness, and thinking that at any rate we felt more hopeful than when we rounded them on the outward journey. We had the stuff on board and a good margin of time for Howth.

Mr Gordon said he would cook the supper tonight and produced a wonderful dish which he called a sweet omelette; it was really buttered eggs cooked with golden syrup but it tasted better than it sounds.

Saturday 18 July 1914

• Gordon Shephard

Round the Longships at last and a fair wind and a lovely morning. But the wind was very light and there was a most abominable swell which upset everything, including our tempers. The question now was, should we put Mr Gordon ashore at St. Ives or chance getting to Milford in time, and we finally decided to run straight for Milford. All day there were alternate calms and light breezes with a lot of swell and the sails Happing and blocks banging in a distracting way. However, we averaged about ten knots, quite one of the most unpleasant days we have had with a thick mist a good part of the time. Molly spent the morning mending a great rent in the foresail, and I trying to make a blouse-stuff and needles being soaking wet and we sitting in oilskins in the cockpit.

No dinner thrown on the floor tonight, but a cup of coffee spilt, to Molly’s grief. ‘Gordon’ she said, ‘You’re ruining the guns with that coffee.’ However, no doubt, Erskine will put carbolated vaseline on them tomorrow. He always does that after they have had doses of tea, coffee and fruit juice spilt on them.

Every stitch of canvas was being set and re-set throughout the night to catch all the wind there was which was constantly shifting, and everyone but me was up from 2a.m. I, having been up two nights, slept the sleep of the just, and only heard through my dreams the shifting and setting of the spinnaker, etc., though my guns are not so comfortable for sleeping on as they were, especially on the starboard tack.

Sunday 19 July 1914

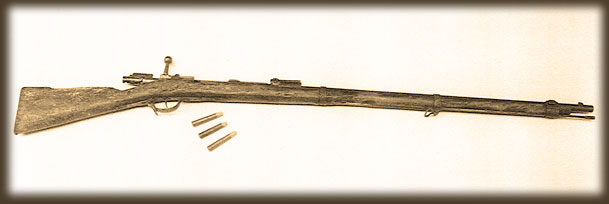

• The Howth Rifle

I woke up fairly early to find everyone in great agitation as to whether we should be in time for Mr Gordon to catch his early train.

We were coming up the long reach of Milford Haven and Molly was trying to help Mr Gordon to pack and collect his clothes from the various bunks in which they were shoved. J looked hastily for some shore clothes and at last discovered some not absolutely rolled into a ball.

I, longing to go on shore, had suggested that Erskine had better stay on board rather than me in case any coastguards came to see the yacht’s papers and that I would buy the provisions we needed (bread, potatoes, butter, onions) and see what we could do about getting water.

At last, Mr Gordon’s lost hat and boots were found and shoved in, the dinghy was lowered and Duggan put us ashore.

Of course, he had landed at the end furthest from the railway station and, stumbling up the steep streets, we started to walk there. It was an endless way and, having had no breakfast, I was not feeling very energetic but we got to a hotel at last and found that there was no train till 6:30pm. The early train only went from a station several miles away. “Do you think we ought to go back and have breakfast on the yacht and spend the morning tidying up?” I said, and then I saw through the open door of the coffee room someone else’s breakfast laid out and it was so tempting. We ordered it in the hotel forthwith and very good it was. I had what Molly calls her “shore appetite” and ate a vast meal. A fellow traveller breakfasting at the hotel was most anxious to know how we fared on the yacht, what sort of a cook we had. “Oh, we’ve quite a good cook; we really manage very well,” said Mr Gordon, looking at me over the marmalade, convulsed with suppressed laughter.

After breakfast we went in search of provisions. I was afraid the Welsh might have tiresome Sabbatarian principles against Sunday trading but not at all. They were ready to sell anything. I spent a £1 before I knew where I was and then a small boy –– Arthur by name –– was awakened from his Sunday sleep and appeared with a handcart on which two large baskets laden with bread, butter, bacon, onions, etc, were fastened and we started off for the quay.

The streets of Milford are very steep and the handcart fairly raced down (Arthur acting as a kind of brake) and Mr Gordon and I, helpless with laughter, running behind. As we panted down the streets after the handcart we crossed the track of the church-goers, very prim and proper in their Sunday best.

But, alas, at the quay nothing could attract the attention of the yacht’s crew. We waved first the Daily Mail, then my white coat, in vain. Mr Gordon, with secret joy, said the only thing to do was to go back to the hotel, sleep and have lunch.

Having had only an hour’s sleep in the night, and being a person like Leonard who sleeps at any odd moment, he was overjoyed at the prospect of bed and no effort of the hotel chambermaid could wake him till nearly 3pm. I wrote letters, read the magazines and day-dreamed (not to mention a scrumptious hot bath) but I felt rather mean at leaving Molly to do all the tidying up on board.

Our meal turned into tea instead of lunch and by the time it was over it was 4 o’clock. I felt very guilty. Not so Mr Gordon. He was quite satisfied. He had had a much better sleep than he would have had in the yacht. “I don’t mind rowing back to say goodbye,” he remarked, and we set off in the rain to walk to the further quay where we finally did manage to attract Asgard’s attention.

Molly received me somewhat coldly and evidently did not believe we had made any serious efforts to attract their attention. She had spent all the morning up and down looking out for us, she said, and would like to have come ashore herself. No wonder the thought of my two shore meals and hot bath was too much for her. I felt all I could do to atone for my misdeeds was to try and cook an extra-good supper.

Mr Gordon finally departed in a downpour of rain, with many promises of coming to Howth on the eventful Sunday. Such rain and half a gale of wind! I was thankful to be safe in Milford Haven instead of rolling about in the Bristol Channel.

Monday 20 July 1914

• The Asgard

Gleams of sunshine between the showers when we woke and it cleared out into a brilliantly fine day with a tearing east wind.

We put off sending ashore for water till the afternoon and had decided to spend another night at Milford, when, just as we were going down to lunch at 2 o’clock, the anchor began to drag. Visions of drifting ashore with half the population coming to salvage us came to our minds. However, Erskine hoisted the mizzen and jib and managed to get the anchor in and we sailed away down the harbour, thinking of looking for another anchorage to spend the night. But Erskine, once we were under way, could not bear to lose a fair wind and thought we had much better go on. Molly was for staying another night in Milford Haven but, as he was so obviously anxious to go, she gave in and we were soon skimming past St Anne’s Head and turning northward towards the Bishop’s Lighthouse. Then, alas, the wind dropped and we drifted most of the night.

A great argument this evening as to what we should feel if Asquith in his statement today announced the repeal of the Arms Proclamation. Molly said she would be quite glad but Erskine confessed to some feelings of disappointment if the Proclamation was withdrawn within 5 days before we were to land the guns and I frankly confessed I should be horribly disappointed.

Tuesday 21 July 1914

• Molly Childers

Still a flat calm but a heavenly summer morning, and after breakfast a little breeze sprang up.

Erskine tried the ammunition this morning and Was much relieved to find it did fit.

An alarm occurred after lunch when we heard a steamer approaching through the mist (it was very thick with a bright sun overhead) and Molly thought it was a warship, it sounded so large, and what she could be doing in Cardigan Bay we couldn’t imagine.

“Let’s cover up the ammunition,” said Erskine, hastily putting two cushions on the two boxes in the cockpit. It turned out to be only the Fishguard steamer going at a great rate, so we must be much further south than we thought.

Wednesday 22 July 1914

Half a gale arose in the night. I was dimly conscious of a great bucketing about, of Molly crawling over me to relieve Erskine at the wheel, and of my continually rolling across the cabin.

Painfully and gradually I got into some clothes and, feeling rather green, staggered on deck where the fresh air soon put some heart into me to cook breakfast.

We were steering straight for Holyhead, having been almost over to the Irish coast during the night, and there was a good sea on. The ammunition boxes sitting in water in the cockpit showed it had been pretty rough.

I managed to produce bacon (of a sort) for breakfast. Erskine, who had had a strenuous night, was very glad of his breakfast though he had charged me not to try to cook anything. He is the most appreciative person to cook for but he has the habit common to everyone on board of starting to do something else just as the food is hot and ready. Molly generally begins to do some elaborate cleaning; Erskine disappears on deck or, worse still, gets out the charts over the breakfast table and takes bearing of the course, and back has to go the food into the oven again. Mr Gordon never attempted to get up till everyone e1se was at breakfast, except on the rare occasions when he shaved, and his food was kept hot as a matter of course.

Molly had a horrid accident this morning. The companion ladder fell on her head and gave her a horrid knock, and she lay down till we were almost in Holyhead.

The race was not so bad as it might have been, though pretty choppy but it was rather touch and go that we were not swept down past the stack by a furious tide. Holyhead, ‘harbour of refuge’, was indeed well-named, I thought as we rounded the breakwater and came up into its calm water after the choppy, angry sea outside.

It was nearly lunchtime when we anchored and Erskine lay down to get half an hour’s sleep before lunch. Molly was in the cabin and I in the saloon, sewing the collar of my blouse, when I heard Pat’s voice on deck saying, “Yacht Asgard,” evidently answering someone. It flashed across me it might be the coastguards.

“Erskine,” I shouted. “Wake up, you’re wanted; they’re asking her name.” But Erskine is very hard to wake and I was just meditating shaking him when he turned over and said sleepily, “What?” “Come on deck,” and I dashed up, he after me. There were the coastguards in a boat close by, calling out questions: “Last port; destination; registered tonnage; owner’s name.” Erskine, now thoroughly awake, shouted prompt answers, some of them truth and some of them fiction and, to our immense relief, they rowed away and we breathed again. Luckily, someone had had the presence of mind to throw a sail over the ammunition boxes in the cockpit.

Molly kept watch on deck all that afternoon while Erskine had a sleep and I went onshore for shopping.

I felt rather weary and weak about the legs after the bucketing we had had last night and dragged myself from one shop to another. Molly, as usual wanting to save me all trouble, had told me to get a cab but they didn’t seem to grow in Holyhead.

I tore open the newspaper and breathed again when I saw the Arms Proclamation was not withdrawn. I also got an Irish paper and found they had been searching all round for gun-runners, some in the Shannon, which was very disquieting in case we had to go round there.

It seemed so odd to find Holyhead was a real town with shops and streets and not just a station with a very long train and a very bright light.

Thursday 23 July 1914

• Erskine Childers

I slept till about 8:30am and was only roused by Erskine calling out to ask when we were going to have breakfast. Almost every morning this happened, though rather earlier, and then Molly would tell me to lie still and that it was much too early to get up. I spent a peaceful morning finishing my blouse as we had settled to spend another night in Holyhead.

The weather was not looking too good; it was raining with a lot of wind from the sw. Erskine came ashore with me after lunch, chiefly to have his hair cut. Meanwhile, I did some more shopping, for we were laying in provisions in case the Howth scheme didn’t come off and we had to go round to the Shannon.

Tea at the hotel was a glorious meal with a wash beforehand that really cleaned my hands which were ruined by a course of gun-grease, potato washing, paraffin and, worst of all, binnacle oil. As we sat devouring hot, buttered toast, marmalade and strawberry jam, I said to Erskine:

“That was a heavenly-looking bath in the bathroom here; I was almost tempted to have a bath.”

“Why don’t you?” he said.

“I’ve had quite a bath quite recently, you know –– Sunday.”

“Yes,” said Erskine, “of course you had.”

“And it’s only Thursday,” I said.

And then we looked at each other and laughed at the thought of what our standard of washing had sunk to.

To bed tonight with the usual howling wind through the rigging and rather dismal forebodings of the morrow for we ought to start for Howth unless there was an absolute gale.

The excitement is almost too great as the time gets near and I have a horrible vision of being weatherbound here. Still, I know Erskine will get across if it is humanly possible to do so. It’s a pity Mr Gordon is not back with us for this final venture.

Friday 24 July 1914

Bad weather still, though the barometer is rising.

Molly acted as alarm bell at 4am, 5am and finally 6am, so one’s night was rather short, but Erskine wanted to get away as early as weather permitted.

We all rather dread the next two days between us and our fatal 1pm on Sunday; crucial days on which so much depends.

We got off about a quarter to 10. Still blowing pretty hard, and cloudy and squally, but we were going ahead fairly well when suddenly Erskine saw a tear in the mainsail. Horrors! We had to put back to harbour again and found there were two or three tears. So Molly sat and I stood on deck in our oilskins and mended the sail in the pouring rain, the sail-needle sticking horribly in the thick seams.

At long last it was done and at 20 past one we started again. As we stood out of the harbour the sun came out, the blue sky appeared and our spirits rose at feeling that we were really off with a clear sky to windward.

We got through the race pretty well and then the wind fell so light that we rolled about in a horrid sea for a bit. A gull followed us for a long time poised just above the mizzen. Molly declared it was Mrs Green thinking of us. Erskine prosaically declared it was the same gull that had finished the remains of the bacon after breakfast and that he was now hoping to get some tea.

We began to be afraid of being becalmed. But that was not to be. At dinnertime a good breeze sprang up, still nw, and it blew harder and harder till by midnight it was a regular gale. It was an awful night. Erskine stayed on deck the whole time. The waves looked black and terrible and enormous, and though everything was reefed one wondered if we should ever get through without something giving way.

For about half the night I crouched in the cockpit or the hatchway, then crawled into the cabin where Molly and I lay, half on top of one another, which seemed to make the elements less terrible but hardly slept a wink all night.

Saturday 25 July 1914

• Molly Childers aboard the Asgard

It was a relief to see the daylight but though the sun came out it was still blowing very hard. Cooking breakfast was bad; eating it almost impossible.

The only ray of comfort was that, in all the storm, Erskine had hit off the right place with his usual genius, and we hove to about 10 miles SE of Howth and gradually progressed towards it during the morning.

I spent the time recovering from last night, sitting at the top of the companion, cold in spite of three jerseys and an oilskin, swept by spray and awful showers but much cheered to think that there was Howth –– the promised land –– thought of and dreamt of during these three weeks, actually ahead of us, and surely the wind must go down sometime.

Lunch was rather a pretence. I managed to eat some biscuits. Molly didn’t even come in. She was desperately tired and no wonder. And Erskine looked worn-out after the storm and the anxiety (not yet over) of calculating the time of arrival.

The wind calmed down a little after lunch and I squatted at the foot of the companion and mended the Cruising Club flag, under which we were to make our entry into Howth tomorrow. It was a job with the yacht rolling so much; however, I got it done at last.

Having got near Howth we sailed on up past Lambay Island and then back towards Kingstown.

“Shall we just go boldly into Kingstown Harbour?” said Erskine. “It’s the most natural thing for a yacht to do after a storm like this and 10 to 1 against any questions being asked.”

For a minute it seemed awfully tempting, tired as we were, to turn into the harbour but, on thinking it over, we all felt we couldn’t risk it. Suppose the cruiser were there and we were searched –– what an ending to the expedition!

So Erskine decided to keep sailing.

There was still a good stiff breeze but it was offshore and the sea much calmer. Cooking quite possible again but, by some carelessness on my part, a drop or two of paraffin got into the stew, which was to have been a special chef-d’oeuvre for the last night. Fortunately, Erskine didn’t notice it and ate quite a good meal, which he wanted badly, but Molly and I did and I’m afraid it made her quite ill.

The fo’castle seats are generally covered with oil and it is hard not to put things down on them in a hurry when everything is tumbling about. My bed wetter than it’s ever been tonight. New leaks have appeared all over the place; however, Molly angelically shared hers with me, so I was only on the edge of the wet part. Everything in the saloon is soaking since the storm –– cushions, mattresses, even my favourite seat on the ammunition box at the fo’castle door.

At supper, Erskine looked doubtfully at the big bunk in the saloon, which was full of rifles, and his sense of duty (always abnormal) getting the better of his fatigue, he said, “I believe I ought to shift those out tonight. What about your packing, Mary?” I was also very tired and my conscience had firmly retired for the night.

“I’m too sleepy. I’ll get up at 5 tomorrow,” I said, and crawled into the cabin half on top of Molly, who was as usual very long-suffering about it, and slept the sleep of the just, dreaming that I was at home again looking over the crops with Muir.

Sunday 26 July 1914

“Six o’clock,” said Molly’s voice. “Time to get up.”

Then Erskine: “Hullo, Mary, how about being up at 5? I want my breakfast.”

I did very little washing that morning for I was hoping for a real hot bath in the evening and if we had to go on to the Shannon, well, Heaven help us, nothing mattered then.

Hopes were high at breakfast. We had just turned back towards Lambay Island, the wind still a fresh north-westerly breeze, and we were up to time. The question now was would the motor boat be there, and as we came along the north shore of Lambay, Molly strained her eyes to catch a glimpse of any craft coming from Kingstown, but nothing so far.

I helped Erskine shift the guns out of the saloon bunk and collected my clothes as best I could, packed them up, and went on deck again.

The time crept on –– 11 o’clock and still no sign. The motor boat was to have met us at 10. We had sailed down the eastern side of the island and back again and my spirits sank to zero. We were to sail in, so Erskine had settled, whether the motor boat came or not. It did seem a risk. We had, of course, no news from the Provisional Committee for three weeks, and perhaps no Volunteers were coming down at all.

We had to get in and out of Howth Harbour with the high tide so there wasn’t much time for delays. As we got nearer I went down and cleared out the guns in our bunk, thinking as I laboured at them that if we had to put out again with them still on board what a dreary job it would be stowing them all back again.

We were close by when I had finished and there was Howth pier plainly visible, and Molly gazing to see if any Volunteers could be seen. We all felt very doubtful about them for we couldn’t think it was too rough for the motor boat to come out and were afraid something had happened to make them give up the whole thing. However, as my red skirt was to be the signal, I stood well up on deck. It was no easy matter with a fresh breeze to lower the sails at just the right moment to run alongside the quay, when minutes might be so precious.

Molly took the helm and Erskine and the men got the sails down, and joy, oh joy –– there was a group of men on the pier-head to catch the rope.

• Signalling Corps of the Irish Volunteers at Howth

Duggan was a bit late throwing the warp and we shot on past the pier-head. But the men got hold of the rope and hauled her back alongside. A quarter to one, up to time to the minute, and a long line of Volunteers were marching down the quay.

There was Mr Gordon on the pier-head and, of course, the inevitable Figgis. Then things began to move.

At first there was a fearful scramble among the men on shore for the rifles as they were handed up. Then Erskine stopped the delivery until he got hold of someone in command and some sort of order was restored. Molly and I and Mr Gordon stood by the mizzen and looked at the scene. It still seemed like a dream, we had talked of this moment so often during the voyage.

Then something happened that we had discussed 1,000 times –– the coastguards from across the harbour put off in a boat to the yacht.

The Volunteers levelled revolvers at them and I was afraid for a minute they would fire but the coastguards, wisely seeing that four men could do nothing against 1,000, rowed off again and in a few minutes they were sending up rocket signals for help.

In about half an hour the whole ship was unloaded.

I got ashore with my luggage and was warmly greeted by O’Rahilly, Eoin MacNeill, Dermot Coffey and who but Pádraic Colum in uniform and looking quite martial*. He pressed me to lunch with them at the hotel, but I had already promised to go to the Coffeys, a plan made that night when we parted at Cowes on the Kelpie.

Then the Volunteers formed up on the quay with their rifles and gave ringing cheers for the yacht and her owners, and several eager Volunteers jumped on board to help hoist the mainsail. They were rather too eager over it and it tore again, this time rather badly, and Erskine decided to hoist the trysail. Luckily it was bent on to the gaff ready, and with Mr Gordon’s help and one or two fishermen it did not take long.

I got on board again while they were settling it and went below, got a broom and tried to clean up the cabin and saloon, which were full of straw, broken glass, etc (the skylight had been broken), so that they could have some prospect of lunch when they got clear. Then on shore again, and this time they were really off, standing out to sea with shouts and cheers and goodbyes.

We watched them till she was well out to sea, I feeling rather mean at having left them to cope with all the mess, and then I turned round in search of my possessions and found I had left my one respectable garment (my white sports coat, which I had cherished for landing in) on board when I went back to tidy up. I still had my dust coat, not looking its best as it had been used for covering up the guns; however, it partially concealed my white jersey and short red skirt. Also, one of my bags had disappeared. They had both been handed up on the quay by Volunteers and one must have been carried off by mistake with the ammunition. I discovered it weeks afterwards at the Volunteer Headquarters. I believe they thought it contained part of a machine gun.

Dermot Coffey seized the other bag and he, Mr Gordon and I proceeded up to their house. It seemed miles but when we got there Mrs Coffey gave us a most warm welcome and a lunch preceded by a much-needed wash.

We heard all about the Kelpie’s doings from Dermot Coffey and compared notes about our experiences in the big storm.

About 5, Mr Gordon and I started back to Dublin and I took him to tea at the Arts Club. Who should I find there but Mr Craig? I was a little embarrassed what to say to him as I didn’t know how much he knew of our doings, though I guessed he must know a good deal about Conor.

He asked me if I had been on the Kelpie. “No,” I said, “I’ve been yachting with friends; in fact, I’ve just landed.” My costume certainly required some explanation. I solemnly introduced Mr Gordon as a yachting friend and we sat at tea and talked sailing shop as if no such thing as gun-running had occurred.

Dublin seemed wrapped in Sunday afternoon sleepiness, and one wondered when the news would reach it, when far down the street we heard a newsboy “Stop Press” and Mr Gordon dashed out and bought a paper. When he came back Mr Craig had vanished out of the tearoom, so further explanations were unnecessary. In all our forecasting of what would happen we never dreamt of firing on the crowd, or indeed on the Volunteers, once the guns were in their possession, as we knew the UVF carried their rifles in Belfast.

I determined to go and try and find Mrs Green at her niece’s house, having had a message through Figgis that she was expecting me. So after having sat some time at the club discussing with Mr Gordon another gun-running expedition on the Santa Cruz (it was all fixed for September 20th, if more guns were wanted and more money could be got, and he was to come to Foynes and pretend to hire the boat), we said goodbye and he went off to catch the boat train, and I to Sandford Terrace.

I found Mrs Green just arriving in a cab as I came up to the door and she was as glad to see me and hear all our doings as I was to see her.

Dr Henry hospitably asked me to stay the night. Mrs Henry was away. I was beginning to feel I could hardly drag myself any longer and I accepted joyfully.

I felt rather mean as I got into a glorious hot bath and thought of Molly and Erskine tired and worn out with everything upset, tossing about on the Irish Sea.

But my bed was heavenly.

* “This is a somewhat baffling entry,” writes F. X. Martin. “Pádraic Colum was a Volunteer and was at Howth on 26 July but he informs me that to the best of his memory he wore no uniform. The Fianna were the only nationalists at Howth who, as a group, were in uniform. Some few Volunteers sported a uniform but the official grey green dress was not decided upon until 12 August 1914.” (See in Martin, Irish Volunteers, 1913-1915, cit, pp132-5.)

MARY ELLEN SPRING RICE was only daughter of Thomas, second Baron Monteagle of Mount Brandon, Mount Trenchard, Foynes, Co Limerick. She was a close friend of the Childers family, a strong supporter of Home Rule and later of Sinn Féin.

She died on 1 December 1924 in the Vale of Clwydd Sanatorium, north Wales, aged 44, after two years’ illness. When her funeral took place at Foynes on 4 December she was given a guard of honour by the local IRA, the Gaelic League, and the trade unionists.