8 May 2012

The 2012 Bobby Sands Lecture – Gerry Kelly MLA, Belfast, Sunday 6th May

'We would not have got this far without the sacrifice of our fallen comrades'

My abiding memory of Bobby at the Christmas party organised by the prisoners in Long Kesh is of him singing ‘Imagine’, the John Lennon song

IT IS 31 YEARS since Bobby Sands’s death on hunger strike. Not only are there people in this hall who were not born in 1981 but there is a whole generation who, thankfully, did not experience that traumatic period.

Seanna Walsh, a close friend and comrade of Bobby, said last year that people who went through that experience “have an obligation to tell a new generation about it – to ensure that this crucial period in Irish history isn’t left to be written by the ‘experts’ and academics but is actually recounted by the people who lived it”.

I agree entirely, because history is not about living in the past but about learning from the past to give us all a better future. And for that we need a true account of history.

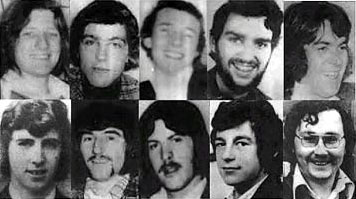

Long Kesh, c1975 – Back row: Seanna Walsh, Gerry Rooney, Jimmy Gibney, Brendan ‘The Dark’ Hughes [d. 2008], Tomboy Loudan, Bobby Sands. Front row: Tom Cahill [d. 2001], Tommy ‘Toddler’ Tolan [assassinated 1977], Gerry Adams

What makes Bobby stand out amongst others of his ilk and generation? What makes him the figure that still inspires people in Ireland and in so many other countries around the world – especially those struggling for freedom? To me, essentially it is simply that his words and actions match: that he was a committed activist but, importantly, also a prolific writer. He explained his actions and the actions of his comrades to people and the people understood.

In this it is important to know that he was an ordinary person living in an extraordinary situation. Perhaps to his own surprise, he found the strength, intelligence and commitment to rise to that challenge. Part of that challenge was to lead from the front.

We can follow his life from a Catholic teenager living in the strongly loyalist area of Rathcoole who enjoyed a bit of craic, loved music and kicked football to his prophetic words written in 1979 when he was 25 years old – two years before his death. He wrote: “I find it startling to hear myself say that I am prepared to die first rather than succumb to their oppressive torture and I know that I am not on my own, that many of my comrades hold the same.”

I am very proud to come from a community and country that has produced and continues to produce courageous people in abundance. Alongside Bobby Sands there are many – too many – who made the supreme sacrifice for the people of Ireland. But Bobby was like an amalgam of many activists: a bit like a fictional hero that you can add extraordinary powers to – except that he was a real person.

As a teenager he was an active IRA Volunteer fighting against heavily-armed

British state forces on the streets of his native Belfast. By the age of 18 he

was a political prisoner sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. By the end of

his sentence he was a musician (thanks in great part to Rab McCullough, another

political prisoner). Bobby had also become a writer.

As a teenager he was an active IRA Volunteer fighting against heavily-armed

British state forces on the streets of his native Belfast. By the age of 18 he

was a political prisoner sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. By the end of

his sentence he was a musician (thanks in great part to Rab McCullough, another

political prisoner). Bobby had also become a writer.

I was transferred back from a jail in England in April 1975 and was in Cage 9 of Long Kesh Prison Camp; Bobby was in Cage 11. At the Christmas concert that year, organised by the prisoners, he and a couple of other musicians were allowed down to Cage 9 for the night. My abiding memory of Bobby is him is singing ‘Imagine’, the John Lennon song. It is in my head because he sang it with passion and it was obvious his beliefs went far beyond any narrow nationalism. The fact that he also liked Leonard Cohen just adds to his persona to me. He also became a Gaeilgeoir by throwing himself into Irish-language lessons.

He was a voracious reader and learned quickly. On his release in 1976 he put to good use what he had learned from reading about other political struggles throughout the world. In Twinbrook in Belfast, where he then lived, he set about reorganising the local IRA, the Auxiliaries, Na Fianna Éireann and Sinn Féin. He had embraced the fact that any political struggle must go far beyond the cutting edge of armed struggle and so he got involved in taking on the British state in every aspect of life and encouraged others to do the same. He wrote for a local news-sheet and for ‘Republican News’.

He also remained an active soldier and after six short months he was back in jail. Having been in prison before, he still saw himself as a political activist and prison as another site of struggle.

He fought the British policy of criminalisation of political prisoners from within the Crumlin Road Jail and then again when he became a ‘Blanket Man’ in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh.

He used his talent at writing to articulate to the outside world (or to anyone who would listen) the truth of the horrendous and oppressive years of protest and systematic brutality in the H-Blocks. After the 1980 Hunger Strike, British bad faith, double-speak and reneging on agreements, made the second Hunger Strike of 1981 inevitable.

Bobby, who had become the Officer Commanding (O/C) of the republican POWs organised for himself to be the first man on hunger strike. He also arranged for a two-week gap before Francis Hughes and the others joined him on hunger strike. He believed that it was highly likely that he would die but hoped that the British Government would move to resolve the situation before others died.

When it was suggested that Bobby run in the Westminster

general election there were many worries and different opinions given. Many

thought it might take away from the effect of the street protests that were ongoing

or if he was not elected it might do damage to the campaign for political

status. It was a huge risk. Modern-day republicanism would be entering

unchartered water. Yet when the decision was made to enter the election,

activists inside and outside jail, whatever their view, put their full

commitment and energies behind the campaign to elect Bobby.

When it was suggested that Bobby run in the Westminster

general election there were many worries and different opinions given. Many

thought it might take away from the effect of the street protests that were ongoing

or if he was not elected it might do damage to the campaign for political

status. It was a huge risk. Modern-day republicanism would be entering

unchartered water. Yet when the decision was made to enter the election,

activists inside and outside jail, whatever their view, put their full

commitment and energies behind the campaign to elect Bobby.

Bobby’s historic election to Fermanagh & South Tyrone was not enough to move the British Government on the prisoners’ five demands at that time but it was a pivotal moment for the future of Irish republicanism – a turning point of substantial magnitude for all our futures.

In the space of a single decade, Bobby Sands – a long-haired, working-class youngster, little known except to a handful of friends and family – had become a revolutionary, a poet and songster, a socialist, a political prisoner, a hunger striker and an elected Member of Parliament. This kid from Rathcoole had shaken the British Establishment to its foundations.

There was a powerful simplicity in the Hunger Strike. Despite the billions of pounds spent by the British Government on a strategy to defeat a political struggle and ideology through the oppression of political prisoners, they could not answer the simple question being asked in many countries and indeed in many languages: ‘Why would anyone go through the horrendous, relentless pain of a prolonged hunger strike to the death if their cause was unjust?’

H-Blocks Hunger Strike Martyrs: Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O'Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine

Bobby, of course, was not alone. Nine other comrades died on hunger strike after him. Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg died from force-feeding and on hunger strike before him in 1974 and 1976. There are many others who lost their lives in the same way in republican history. But tonight we commemorate Bobby Sands.

It was the David and Goliath battle between a huge and powerful British Government and a strong will in the frail body of a hunger striker that is the enduring image and reality of the 1981 Hunger Strike.

Who of my generation does not remember where they were

when they heard of Bobby Sands’s death? I was in Cage 9 of Long Kesh, within a

few hundred yards of the prison hospital. I remember watching his mother on the

news telling the world “My son is dying” just a few short hours before he

passed away. I stood amongst comrades in the Nissen hut in absolute silence. We

all went with our own thoughts to our prison bunks.

Who of my generation does not remember where they were

when they heard of Bobby Sands’s death? I was in Cage 9 of Long Kesh, within a

few hundred yards of the prison hospital. I remember watching his mother on the

news telling the world “My son is dying” just a few short hours before he

passed away. I stood amongst comrades in the Nissen hut in absolute silence. We

all went with our own thoughts to our prison bunks.

I wrote my thoughts down till the news flash came through that Bobby was dead. It was only months later that I returned to the verses I had written and realised it was more about his mother, Rosaleen, than about Bobby himself. I reduced 20 verses down to four short ones:

Bobby’s Mother

Rosaleen Sands

You do not know me

I saw you only

On a television screen

When so reluctantly you announced

“My son is dying”

Standing with such dignity and calm

In the deep well of your grief

I felt an intruder

To your private torment

Witness to a mother’s

Naked mourning

Thank you

For allowing us to share

Your precious final moments

With a great man

Bobby Sands came to represent, to symbolise, a generation of Irish republican activists. So unwillingly, unknowingly, his mother Rosaleen Sands became to me, a symbol of what so many families have suffered during that dark period of our history.

I have spoken at many commemorations for comrades, some of whom were also friends or relatives. I have always said that I can’t speak for them, that I don’t know what they might think tonight or have said had they have been standing here in my place.

However, I do know that we lose many of our best in conflict and for those who survive the duty is to take up their mantle and to lead as best they can in the here and now.

I do know that the Hunger Strike was

a political watershed, that it allowed the bulk of republicans to realise that

elections are another site of political struggle. I do know that the stronger

we are the more we can do to help those who need help most. The stronger we are

the closer we get to our primary goal of a united Ireland. I know that, in

1916, republicans used the relevant tools they had at their disposal at that

time as they did in the 1970s and in the 1980s after the Hunger Strike period

as well.

I do know that the Hunger Strike was

a political watershed, that it allowed the bulk of republicans to realise that

elections are another site of political struggle. I do know that the stronger

we are the more we can do to help those who need help most. The stronger we are

the closer we get to our primary goal of a united Ireland. I know that, in

1916, republicans used the relevant tools they had at their disposal at that

time as they did in the 1970s and in the 1980s after the Hunger Strike period

as well.

But today we must also use the relevant tools for the 21st century, for 2012. This isn’t 1916 or 1970 or 1980 or 1990 or 2000. We are going from strength to strength, North and South. That we come from and represent our communities is essential to our politics. We have collectively achieved a massive amount. We have collectively much more to achieve.

We would not have got this far without the sacrifice of our fallen comrades. Taking risks has always been one of our strengths.