1 February 2016 Edition

NIO political vetting - A licence to kill?

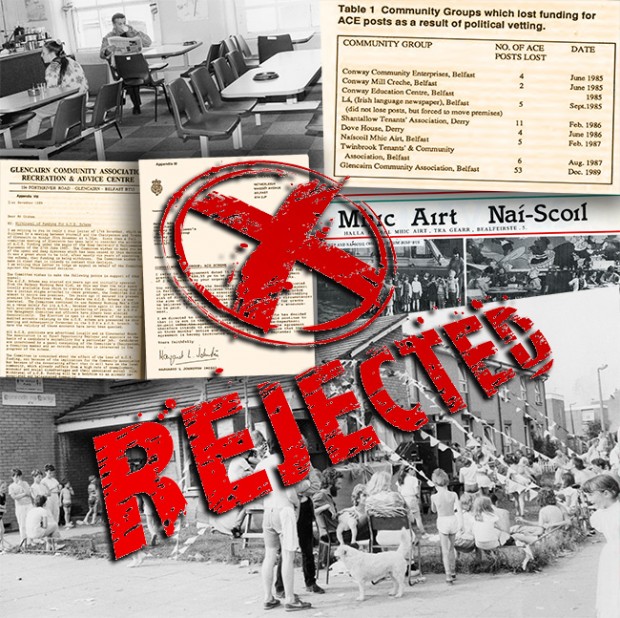

• Many community groups were hit by NIO political vetting

At the core of political vetting was the need of the British Government to control, directly or indirectly, community initiatives, including job-creation initiatives

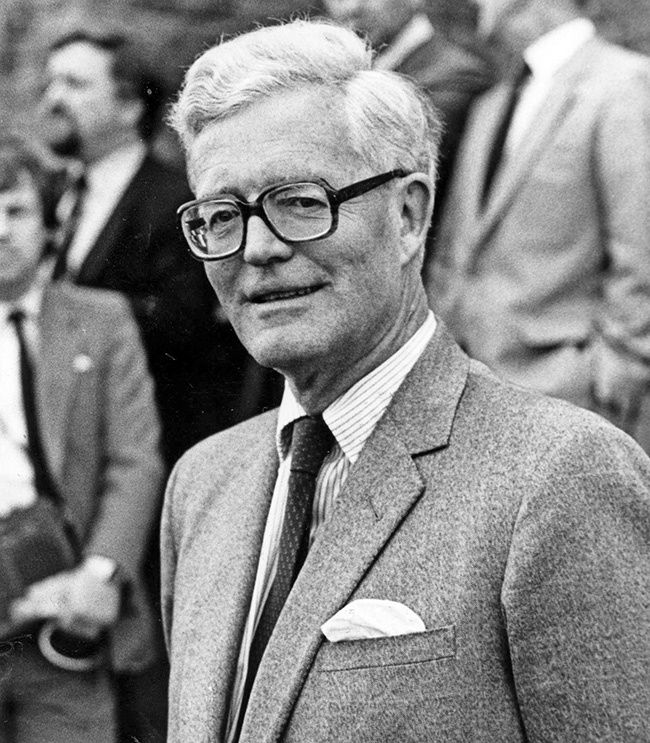

Full text of Douglas Hurd’s statement reads

"I am satisfied, from information available to me, that there are cases in which some community groups, or persons prominent in the direction or management of some community groups, have sufficiently close links with paramilitary organisations to give rise to a grave risk that to give support to those groups would have the effect of improving the standing and furthering the aims of a paramilitary organisation, whether directly or indirectly.

"I do not consider that any such use of Government funds would be in the public interest, and in any particular case in which I am satisfied that these conditions prevail, no grant will be paid."

Hurd’s remarks are very similar to those made by his Cabinet colleague, Douglas Hogg, who declared in the British Parliament that some solicitors in the North were “unduly sympathetic to the cause of the IRA”. Within weeks, on 12 February 1989, Belfast lawyer Pat Finucane was shot dead by a UDA gang consisting of British agents.

• Douglas Hurd

On 27 June 1985, the then British Secretary of State in the North, Douglas Hurd stood up in the British parliament to say he was satisfied that people working in certain community groups across the North had links to “paramilitary organisations” and it would be a “grave risk” to fund these groups as it would have the effect of furthering the aims of these “paramilitary organisations”.

On exactly the same day, a letter was dispatched from the NIO-controlled Department of Economic Development (DED) to the Conway Mill Women’s Self-Help Group in west Belfast. It told them that British direct rule minister Hurd was stopping their funding as it was “not in the public interest”.

The funding referred to in the DED letter had been allocated to the group just four months earlier, in February, and was used to pay two Action for Community Employment jobs scheme workers.

Thus the ‘Hurd Declaration’ was announced and put into action on the same day. With it began a witch-hunt that put community workers, creche assistants, Irish-language enthusiasts and ‘black taxi’ drivers in the gunsights of loyalist killers.

Professor Bill Rolston, now retired from the University of Ulster, asked in his contribution to the 1990 community report, The Political Vetting of Community Work in Northern Ireland:

“What crime had the Women’s Self-Help Group committed? Running a creche?”

Rolston explained what the reason for the “victimisation” was:

“They had the temerity to set up their creche in a building which was a prime target for Douglas Hurd and his officials, the Conway Mill.”

So why was Conway Mill, which promoted numerous indigenous, community-based economic enterprises – as well as community education projects – targeted and identified by the British state as a site of dangerous subversion to be closed down?

Writing in his Léargas blog in 2010, Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, reflecting on the significance of the ‘The Mill’ and its symbolic relationship to not only the people of west Belfast but further afield, said the British Government turned its attention on ‘The Mill’ after it hosted an independent, community-based inquiry into the killing of Seán Downes who was shot dead with a plastic bullet fired by the RUC in August 1984.

While Adams’s contention, backed by other contemporary records, is correct insofar as it identifies the Downes Inquiry as the excuse the British hid behind in their campaign against Conway Mill, there are the wider aspects to Hurd’s political vetting strategy to be considered.

Bill Rolston, again writing in the The Political Vetting of Community Work, sets the British strategy in a wider context:

“In the aftermath of the republican Hunger Strike in 1981 and the consequent rise of Sinn Féin, the NIO increasingly became involved in a new phase of what might be called quite simply counter-insurgency – the battle for hearts and minds in working-class areas where the victimised community groups operate. At the core of this battle was the need to control, directly or indirectly, community initiatives, including job-creation initiatives.”

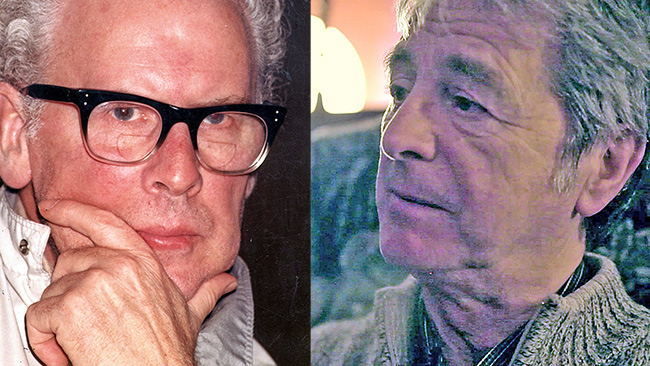

• Community activist Fr Des Wilson and Professor Bill Rolston

Another University of Ulster academic, Terry Robson, in his book The State and Community Action outlined two differing views of the Action for Community Employment jobs programme introduced in the North in 1980s and which many saw as central to the battle for hearts and minds outlined by Rolston.

Robson writes:

“The promotion of the Action for Community Employment (ACE) programme was regarded by many community leaders as a significant contribution to local development, both as a training scheme and as a contribution to local employment.

“On the other hand, there is much to suggest that the use of the ACE programme provided an excellent opportunity for the state to counter the growing influence of Sinn Féin on the streets by instantly neutralising selected community groups and rendering them ineffective as a focus for local political activity.”

Mary Nelis reinforced the latter view when writing about the experience of those in the Dove House Community Resource Centre in Derry’s Bogside, which was also targeted and vetted, consequently losing its funding.

She added another layer of political intrigue to the debate when she argued that the ACE scheme gave the British Government “the opportunity to create power blocs of people who are, in the Government’s estimation, politically acceptable. Groups such as the Catholic Church and SDLP have now become Government brokers for schemes in the community.”

Therefore the ACE scheme, which had the potential to benefit communities, was used by the British Government in its battle against community organisations whose ethos set them outside the political parameters set down by the British.

Terry Robson broadened the debate, saying that the problem for the British began “in the wake of the political crises after 1969, when social problems reached boiling point, the creation of organisations aimed at working-class empowerment rather than dependency gave a distinct and, for some in government, ominous appearance of being politically motivated”.

This is clearly a reference to the way in which nationalist communities developed strategies for self-help and built their capacity in ways that challenged the state.

By linking these groups to Sinn Féin, the NIO sought to legitimise its political vetting strategy by fusing it with the propaganda war they were waging against the party.

And they had no shortage of allies willing to jump on the bandwagon and demonise the party and those groups who were targeted.

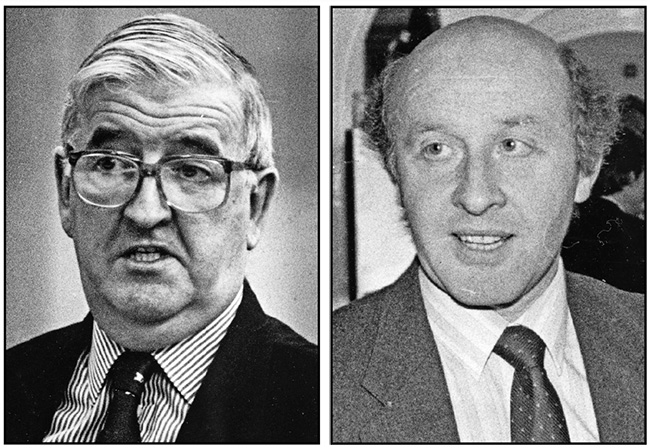

Then SDLP Councillor Brian Feeney insisted that “certain so-called community centres” were in fact “Provo fronts” and all their Government grants should be stopped.

An interesting twist to the political vetting programme emerged in August 1990 when the west Belfast branch of the Irish-language group Glór na nGael was told its funding was to be axed.

The group drove the campaign for the erection of Irish-language street signs, challenging Stormont’s 1949 Act which ruled that street signs could only be in English.

But it was their campaign against Tory NIO Education Minister Brian Mawhinney’s proposals to reduce the status of Irish language in schools, a campaign that angered the arrogant (and Belfast-born) Mawhinney so much that observers believe it was the reason why the organisation was targeted.

Then in October, when it transpired that the RUC had given Glór permission to carry out a street collection in Belfast city centre, it exposed the lie that security rather than political reasons had been the reason why its funding had been cut.

This contention is vindicated by secret British Government papers released in January under the 30-year rule in which the head of the Civil Service at the NIO, Ken Bloomfield, sent a memo to the RUC stating that the Falls Taxi Association (as it was then known) had “close links with paramilitary organisations”.

The memo was very specific in linking the association and its drivers to the IRA, saying “the drivers probably have to pay contributions to the Provisionals from their earnings and they are expected to buy diesel from and be serviced at a Provisional garage”.

• Ken Bloomfield and Brian Feeney

Una Marron and Maura McCrory, of the Falls Women’s Centre, also writing in the Political Vetting report, summed up the reality for those groups and their workers who were vetted. “One of the most disturbing aspects of this type of political vetting is that although allegations are made against them and slanders freely spread, there is no legal redress, no right to appeal and no right to reply. Workers and users are put under threat and, tragically, may even lose their lives.”

And some people involved or associated with the organisations that were politically vetted did lose their lives.

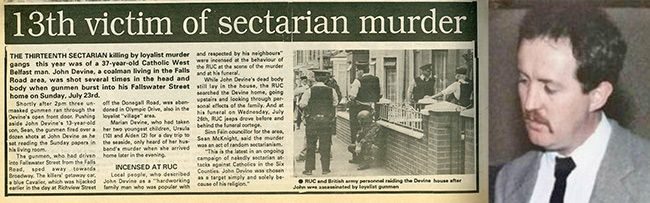

• Loyalist victim – John Devine, whose business was based in Conway Mill, was gunned down in his home in 1989

‘Black taxi’ drivers were regularly targeted by loyalist gun gangs, leaving several members of the association dead and many more wounded; John Devine, whose coal delivery business was based in Conway Mill, was gunned down in his Fallswater Street home in 1989.

Despite the challenges and dangers created by political vetting, the efforts of the communities affected – with support from across Ireland, from Britain, Europe and the USA – saw the people come out the other end stronger.

And we do well to take inspiration from the words of the renowned community activist, Fr Des Wilson, who (along with the Cahill brothers, Tom and Frank) was the driving force behind the development of community enterprises across the city.

Delivering the West Belfast Economic Forum’s Frank Cahill Memorial Lecture in 1998 entitled ‘We Didn’t Take No for an Answer’, Fr Des said:

“The struggle against vested interests on the one hand and bureaucratic indifference was long and tedious but in the end successful.”

And it was successful because of the resilience of many communities, organisations and individuals who refused to have their voices silenced or to have their identity, drive and creativity crushed by governments ideologicaly hostile to true grassroots development.