7 December 2018

Richard Coleman – Usk Jail death 1918

Remembering the Past

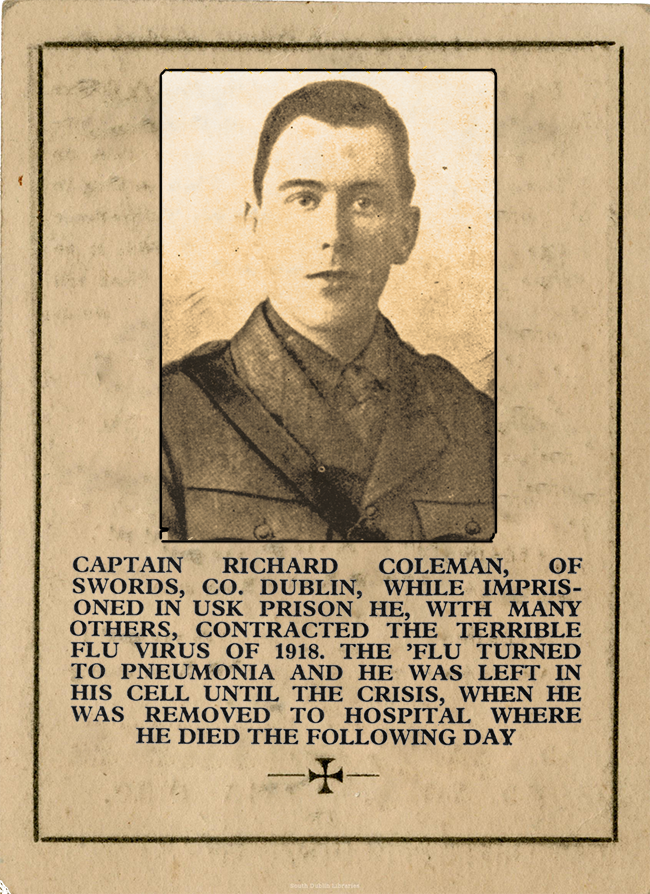

The flu epidemic that swept across Britain and Ireland in 1918 struck at the weak and elderly in society. Hundreds died and many more spent many weeks crippled in agony in their beds during the winter months.

Richard Coleman was born in Dublin in 1890, one of eleven Coleman children, most of whom were active in the Gaelic League. Brought up in Swords, County Dublin, Richard was a religious and a patriotic young man. He trained to be a Christian Brother, but left to begin a career with the Prudential Insurance Company.

When Thomas MacDonagh came to Swords in April 1914 to recruit members for the recently formed Irish Volunteers, Richard was among the first to join. When John Redmond forced a split in the Volunteers later that year, the remaining Volunteers elected Richard as their captain.

On Easter Sunday 1916, Richard mobilised his men, the Fingal Battalion, at Saucers Town, ensured that they were ready for what lay ahead and dismissed them till the following day. On Easter Monday they, along with other Volunteers from surrounding areas, came under the direction of Thomas Ashe, whose instructions were to prevent British reinforcements from reaching Dublin. They fulfilled that task heroically that week.

On the Tuesday, 20 Volunteers were sent into the GPO in response to a request from the Commander-in-chief, James Connolly. On reaching the GPO, the group was split up. Six men became the tunnelling unit around the GPO - `the engineering corps' - while the others under Richard were instructed to reinforce the garrison under Sean Heuston in the Mendicity Institute. Connolly's parting words to them did not augur well for their mission: ``I don't think you will all get there, but get as far as you can.''

They got as far as the Mendicity Institute unscathed. A Volunteer at one of the barricades they passed through said of them: ``In the midst of the firing, 18 (or perhaps less) men approached up Church Street towards our barricade. When they reached it, they passed briskly towards their objective - whatever it might have been. They were dressed and, I thought looked, like countrymen... I could not but admire very much they way they went into action.''

At the Mendicity Institute, the garrison was under severe pressure, with the British attack coming virtually from all directions. By Thursday, things were hopeless and Sean Heuston was forced to surrender to a much larger British force.

They, similar to the other captured Volunteers, were corralled at the Rotunda Hospital for identification purposes. They were then court-martialled and sentenced. Richard was sentenced to death, though this was commuted to three years' penal servitude.

The sentenced prisoners were transported to Dartmoor Jail in England first and then divided up. Richard was sent to Lewis Jail in Kent. When they were released after a very successful campaign in Ireland and abroad for their freedom, each Volunteer was granted £100 from the National Aid Fund in America to help them rebuild their lives. They all pooled their money and began the New Ireland Friendly Society, with Richard as a director and a trustee with a superintendent's wage.

Like many of the other released prisoners in June 1917, Volunteer Richard Coleman of Swords travelled to Clare to help Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers in their efforts to get Eamonn de Valera elected in the by-election.

While there he addressed the first uniformed parade of Irish Volunteers to be held since 1916. For this, he was arrested and jailed for six months. While in Mountjoy Jail, he and the other prisoners went on hunger-strike, led by Thomas Ashe. Ashe's death led to such a public outcry that the remaining prisoners were first moved to Cork Jail and then Dundalk Jail before being finally released.

Richard was not to remain `at large' for long and he was again arrested, along with many of the other republican leaders who'd been active in rebuilding the Movement, as part of the British authorities' `German Plot' conspiracy.

The prisoners were assembled first in Dublin Castle on 17 May 1918 and were then divided up and sent to Usk and Gloucester Jails in Britain. Conditions were harsh in the jail and attempts were made to criminalise them with the order to wear prison uniforms. They resisted and at the direction of the Home Office the prison governor, Mr Young, capitulated. On their first night in Usk, the internees won the right to free association, the right to receive and send letters, to smoke and to wear their own clothes.

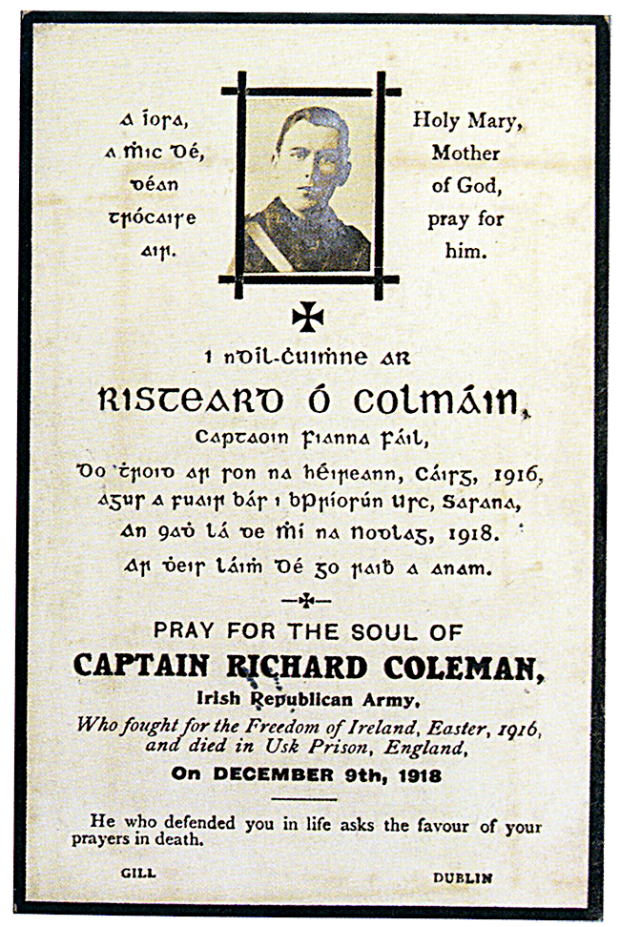

Despite their victory, the prison regime and their confinement weakened the men and with the onset of a severe winter, many succumbed to the influenza virus which had reached epidemic proportions, killing hundreds outside the prison walls. Richard was among a group of POWs struck down by the virus - they were left in their damp and cold cells for three days after the flu struck them down. On 1 December, a new prison doctor, Dr. Morton took up his new duties in the prison and immediately he diagnosed that Richard had now suffering from pneumonia and he had him transferred to hospital. He died a few days later on 9 December 1918.

Remembering the result of Thomas Ashe's inquest - that the prison authorities were culpable - no formal inquest was allowed and when Richard's brother arrived he was prevented from getting an adjournment of the local inquest so as to instruct a solicitor. The local inquest heard Richard's brother state that Richard was a strong healthy man at the time of his arrest, while three fellow POWs attested to the insanitary conditions in the jail and that improper nursing contributed to his death. These statements got good publicity in the Irish press and added to the campaign to get the POWs released.

Richard Coleman's remains were released to his brother and were taken to Dublin where they lay in state for a week in St Andrew's Church, Westland Row. Over 100,000 people filed past the coffin to pay their last respects. Volunteers in uniform formed a guard of honour during that time. A public funeral procession in driving rain from Westland Row to Glasnevin was followed by over 15,000 people. Three volleys were fired over the grave in Glasnevin Cemetery by six Volunteers despite a huge police presence. The size of the crowd prevented the police from moving against the Volunteers.

Volunteer Richard Coleman's death in an English jail, aided Sinn Féin campaign against Britain's occupation and their general election campaign which was in full swing at this stage, and two weeks later Sinn Féin won a landslide victory of parliamentary seats. A month later in January 1919 Sinn Féin MPs met as Dáil Éireann for the first time. The escape from Usk Jail (see AP/RN January 28 1999) by four of Richard's comrades on the same day saw that republican POWs were unbroken and unbowed by their comrade's death.

Volunteer Richard Coleman died of pneumonia in Usk Jail on 9 December 1918, 100 years ago this week.

(additional research by Nigel Heffernan)

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures