27 November 2017 Edition

'6 into 32 – Finding a place for the North in a united Ireland’

Chris Hazzard MP speaking at the Lighthouse Summer School in Killough, County Down

• Sinn Féin MP Chris Hazzard

No longer is it just ‘ourselves’ in Sinn Féin talking about Irish reunification

EIGHTY YEARS AGO, in 1937, Prime Minister James Craig was in his office in Parliament Buildings at Stormont. A Dubliner by the name of George Duggan was a senior civil servant at the time and was with the unionist leader as he finished up his papers for the night.

Duggan later recalled that Craig was in a particularly sombre mood that evening and that, standing at the window looking south over the Castlereagh Hills, he had remarked:

“Duggan, you know that on this island we cannot live always separated from one another. We are too small to be apart, for the Border to be there for all time. The change will not be in my time but it will come nonetheless.”

Some 80 years after Craig’s somewhat prophetic pondering, another political leader – Guy Verhofstadt, the former Belgian Prime Minister and current EU Parliament Brexit Co-ordinator – also felt it necessary to discuss the future of the Border in Ireland.

Mr Verhofstadt, following a visit to the Border region, addressed the Dáil, saying:

“The Border meanders for 310 miles through meadows, forests, farmland, it cannot be securely policed . . . It is an illogical divide, one that, at the very least, should remain invisible.”

For me what makes these two contributions so valuable to today’s debate on Irish reunification is the fact that neither example is motivated by any notion of nationalist sentiment; nor is either contributor a well-known Irish republican – quite the opposite.

With this in mind I think there is much to be gained by considering the political context – and perhaps most specifically the economic context – to both statements.

By the late 1930s, the Northern Irish economy was in serious trouble.

Traditional industries such as linen, and shipbuilding were in decline. With the industrial growth of the Second World War period still a few years away, Craig was obviously worried about the future viability of the Northern state – a state very much still in its infancy.

• EU Brexit Co-ordinator Guy Verhofstadt meets Martina Anderson MEP, Mary Lou McDonald TD and Michelle O’Neill MLA

Verhofstadt’s remarks, of course, are set against the Brexit catastrophe which is currently unfolding all around us.

The prospect of a new European frontier across the island of Ireland makes no sense to the Belgian MEP. As he said, “it is illogical”. He also understands the very real threat that a copper-fastened Border in Ireland represents to the Good Friday Agreement and the Irish Peace Process.

It is in this context – economically, politically and indeed socially – that Brexit has re-energised and reshaped the debate about Irish reunification.

No longer is it just ‘ourselves’ in Sinn Féin talking about Irish reunification.

Fine Gael are talking about preparing a White Paper; Fianna Fáil too are set to publish their own ideas on ending partition; and here in the North the SDLP called for a post-Brexit unity referendum during the recent Westminster election.

Quite simply, Brexit has swept away the old assumptions about the constitutional, political and economic status quo in Ireland.

There is an obligation now on all political leaders, civic society, and the media here to examine new constitutional, political and economic arrangements that better suit all of our needs going forward.

For our part, Sinn Féin believe wholeheartedly in a new, reunified Ireland – but this must be significantly more than merely submerging the 6 into 32 and creating an extension of the Southern Irish state as it currently exists.

Rather, it is an opportunity to shape a new Irish state in the interests of all of its citizens and finally bring to life the vision at the very heart of the 1916 Proclamation.

For those of us who are persuaders for Irish reunification, this is our task if we are to meet the challenges of building a truly new republic.

A new republic where the rights of citizens are enshrined in every stitch throughout the fabric of the state; where the complaints of the disenfranchised and the downtrodden are no longer ignored but examined and removed.

A new republic where the corrosive boils of sectarianism and division are lanced and a truly, modern, inclusive constitutional republic is built in the image of all of its citizens – whether you come from Ballymena, Ballymun or Bangladesh.

There can be no doubt that successive Dublin governments have hollowed out the heart of the 1916 Proclamation. They have stripped away the values embedded in the 1919 Democratic Programme.

Partition and the counter-revolution have achieved nothing but a cycle of economic failure, emigration, inequality and two political states weighted against the rights of citizens – against the interests of Irish men, women and children.

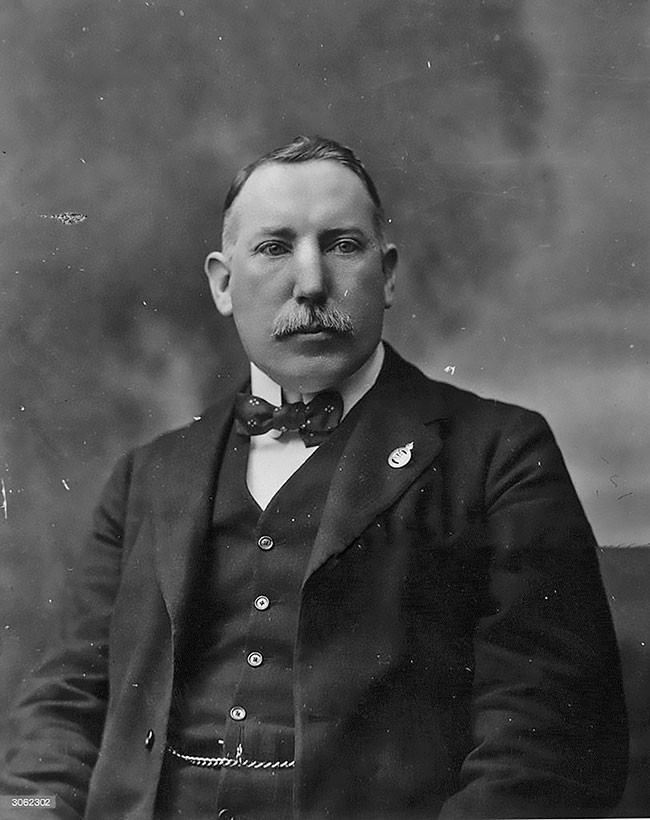

• Unionist Prime Minister Craig: ‘We are too small to be apart, for the Border to be there for all time’

We too, the persuaders of Irish self-determination, have much to reflect on if we are to be ultimately successful in the time ahead.

I would suggest that – for all the reasons why nationalist Ireland has had little success in reconciling unionism to Peadar O’Donnell’s assertion that ‘we are the same people’ – the most striking has been a complacency in regards to not only the strength of unionist opposition to the nationalist doctrine but perhaps, more significantly, the legitimacy of such an opposing ideological position.

Unionists have too often been viewed as nothing more than puppets of the British political elite and obstructions to the inevitable march of history.

Unsurprisingly, such perspectives have remained ingrained in the national psyche for the best part of a century. Such suspicions of ‘perfidious Albion’ were not merely confined to political literature and fireside stories but actually became enshrined in the very constitution of the new Irish Free State.

It’s also fair to say that, in recent decades, British identity has been growing increasingly comfortable in Ireland – not merely as a result of the Peace Process but a reflection of the fact that there are now approximately 150,000 British citizens living in the South – never mind the many more who reside here in the North.

Eighty years after Viscount Craigavon reflected on the long-term viability of the Northern state, many more also now think the time has perhaps come to consider such change.

There is no doubt that the unprecedented political situation created by Brexit has transformed the debate on Irish unity for many, and perhaps most markedly for those unionists who are now disillusioned with the trajectory of the British Government.

While there has been virtually no constructive engagement by the unionist political parties on the issue, the appeal of being part of a modern, reconciled Ireland at the heart of Europe is one which will prove ever more attractive to growing numbers of the unionist community.

This includes young, educated, outward-looking people from a unionist background who seek – on a whole range of social and political issues – to cast off received attitudes; attitudes which for many are the product of incorrigible sectarian segregation and the dominance of a deeply conservative unionist ideology.

Many young unionists wish to live in a progressive and outward-looking society, not one limited by ultra-conservative political factions and a trend towards British isolationism.

Those of us who believe in a reunified Ireland must now increase our engagement with unionism and seek to persuade that part of our society to support Irish unity.

The British identity of many citizens in the North can and must be accommodated in any reunited Ireland. Undoubtedly, this will involve constitutional and political safeguards.

It will require protections for the unique identity of Northern unionists and the British cultural identity of a growing number of people throughout the island of Ireland. It may well require transitional political arrangements, which could mean devolution within an all-Ireland structure.

We should not be afraid to examine any option.

• Brexit has swept away the old assumptions about the constitutional, political and economic status quo in Ireland

A new, united Ireland will be pluralist, inclusive and accommodating to all our people in all their diversity.

With this in mind it is important to stress that the Orange tradition is an Irish tradition.

The reality is that the history of the Northern, Protestant, Orange community has influenced the development of Ireland as it is today and it must influence its future.

Kevin Meagher, a former adviser to British Secretary of State Shaun Woodward, put it well at a recent conference on a united Ireland when he said:

“For unionists, this is not a process where Orangemen are expected to become GAA enthusiasts. Remember the Twelfth in a united Ireland. Wear the sash your father wore. Have a British passport as well as an Irish one. Toast the Queen.”

Let those unionists who are interested in talking to resolve these issues take the mature and necessary approach to overcome these challenges. Let’s talk about building an agreed Ireland together with rights and equality at its core.

All our people, from all backgrounds and traditions, must be involved in the discussion.

Together we can build a future beyond partition, sectarianism and division and a society that serves the interests of all the people who share this island.

It is clear that a greater numbers of unionists are considering if the time has come for constitutional change as outlined by James Craig, for, as Guy Verhofstadt discovered, there is no logic to be found in partition.

But for those of us who are persuaders for Irish reunification – we would do well to remember Georg Lichtenberg’s quip that “for even if professors would join men at the head, nature has joined them at the heart”.