4 September 2017 Edition

The Protestant tradition and the fight for the Republic

• Protestant Irish-language activist Linda Ervine with Sinn Féin's Carál Ní Chuilín

The Protestant contribution to Irish nationalism and modern Irish identity has been critical in defining Irish republicanism itself

FOR most Northern nationalists, talk of Protestant culture evokes images of coat-trailing Orange marches set on provoking and belittling local nationalist communities in pursuit of the old certainties of Protestant supremacy and discrimination against Catholics.

But, as Gerry Adams, the Sinn Féin President, pointed out in a recent speech, the Protestant contribution to Irish nationalism and modern Irish identity is much more than that. Indeed, It has been critical in defining Irish republicanism itself.

It was the French Revolution of 1789 that gave the inspiration for an Irish version of that rejection of feudalism and landlord power advocated by the United Irishmen.

Protestants, mainly Presbyterians, were the intellectual powerhouse of this incipient Irish republicanism, though Catholic emancipation and equality were recognised from the start as essential components of the new order that republicans wanted to create.

The French Revolution had proclaimed the equal rights of all citizens (though with some considerable tardiness in respect of women). It was also less than respectful of linguistic and national differences within the French state but was adamant in its rejection of supremacy for aristocrats or special sections of the state.

Theobald Wolfe Tone expressed this idea in Irish terms, which became the hallmark of Irish republicanism. He stated that it was Ireland’s status as a colony ruled by England that was the cause of all the inequalities and injustices of Irish society.

His aim, therefore, he declared, was “to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country”.

And the way he proposed to achieve that aim was to “substitute the common name of Irishman in place of the denominations of Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter”.

It is a sad irony that the vast majority of Northern Protestants today – the descendants of the republican rebels of 1798 – have been persuaded that the “connection with England” is the guarantee of the dignity and rights of the Protestant community.

While there can be no room for Protestant supremacy in an Irish Republic (any more than there could be room for Catholic ascendancy) it is vital for the establishment of a real Irish Republic that the Protestant community be won over to take its proper place in the ranks of Irish democracy.

This Irish Republic is not and cannot be a mere extension of the 26-county state over the whole island – a state which since its inception by Act of British Parliament in 1921 has been totally subservient to and collaborative with imperialism – firstly of Britain itself and latterly of the European Union.

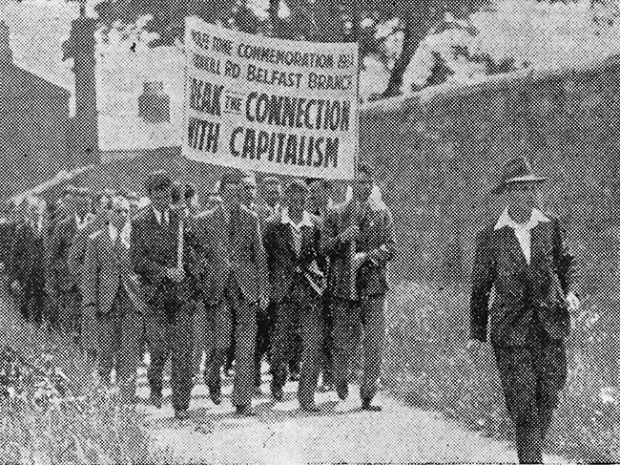

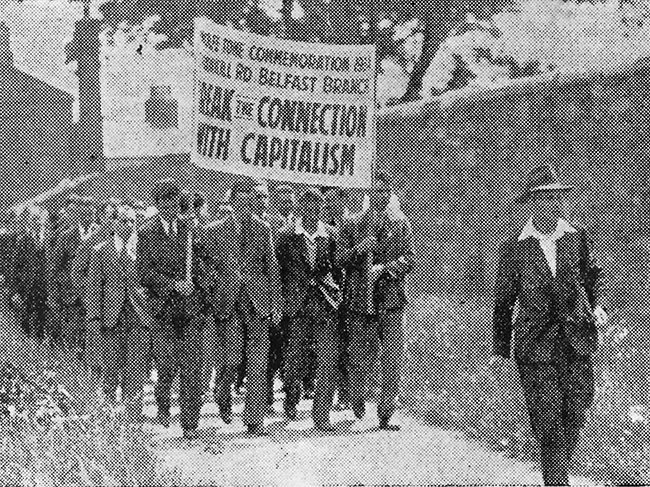

• Shankill Road men march at Bodenstown in 1934 to honour Wolfe Tone

No, the Irish Republic we should strive for is one of equality and parity of esteem for all, one which uses the resources, intellectual and material, of the state, for the common good of all, and one which takes pride in our inherited culture, language and commitment to international peace.

It will be built by Catholic and Protestant together, rejecting exploitation and austerity.

And it will be built by respect for the assertion of individual independence which Protestantism brought to Ireland, as well as a deep pride in our history of struggle and the richness of our culture.

Today, as the political forces of unionism for the most part dig themselves in against an Acht Teangan, which would recognise the rights of Irish speakers and the special significance of the language for our nation, it is worth remembering that Gaelic is as much part of the Protestant heritage as it is of the Catholic.

Large numbers of the Protestant settlers who came to the North came from Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland, such as Galloway. Indeed, the Presbyterian Church maintained for many years a requirement that its ministers be able to preach in Irish as well as in England (a recognition that Irish was widely spoken by its members), and much work for the preservation of the language which was carried out by ministers like the Neilson father and son.

By contrast, during this period, while larger proportions of Catholics spoke Irish, institutionally the Catholic Church regarded Irish as a complicating factor in its main aim of using Ireland as base for the re-Catholicising of England.

There is certainly nothing intrinsically non-Protestant, let alone anti-Protestant, about the language and the campaign for recognition of language rights.

And let us note that the Apprentice Boys, the working class of their time, slammed the gates shut against a feudal monarch. Is that something that should be acknowledged not just by Protestants but by all Irish democrats?