1 August 2017 Edition

The First Hunger Striker

The centenary of the death on hunger strike of Thomas Ashe occurs this September

• Thomas Ashe

The political prisoners’ demands were: free association throughout the day; work of their own choice; separation from non-political prisoners; and to be allowed books, writing materials and more letters and visits

By Patrick McGlynn. First published in An Phoblacht/Republican News , 4 July 1981

THE first Irishman to die on hunger strike was Thomas Ashe, who died at the age of 32 on 25 September 1917 as a result of being forcibly fed in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin.

Born in Kinard, near Dingle in County Kerry, on 12 January 1885, Thomas Ashe learned the Irish language from his father and kept a life-long interest in Irish culture and history.

Whilst training to be a teacher in County Waterford, Thomas became active in the Gaelic League, organising Irish classes and feiseanna and at the same time began his involvement in the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Sinn Féin.

After qualifying as a teacher in 1907, he spent a year in his native Kerry until he became principal of Corduff National School at Lusk in County Dublin, where he taught until Easter 1916. At Lusk he was closely involved in the Gaelic League, becoming a member of its governing body along with Seán MacDermott, Sean T. O’Kelly, Eamonn Ceannt and The O’Rahilly who, like Ashe, were also members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

Thomas Ashe joined the Irish Volunteers after its formation in November 1913 and founded a unit in the Lusk area. By 1915 he was training the local Volunteers on intensive military exercises and manoeuvres; by 1916 he was Officer Commanding the 5th Dublin Battalion in the north county area known as Fingal.

On Easter Monday 1916, on Pearse’s orders, Ashe mobilised his battalion of 70 men, destroying enemy communications and blowing up the Dublin to Belfast railway line. During the week he captured all the Royal Irish Constabulary police barracks in the area and on the Friday of Easter Week moved on to Ashbourne in County Meath.

The Ashbourne RIC garrison, surrounded by Ashe’s men, quickly surrendered but shortly afterwards the Volunteers were engaging a convoy of 20 RIC cars bearing 80 policemen approaching from Slane. After five hours of fighting, the RIC men scattered, leaving 11 of their number dead and 20 injured. Two of Ashe’s Volunteers were killed in the battle. The following Sunday, having been victorious all week, Ashe received Pearse’s general order to surrender and he obeyed it.

Taken to Kilmainham Gaol, Thomas Ashe was court-martialled and sentenced to death. This was later commuted to penal servitude for life and he was transferred to Dartmoor Prison in England, from where he was released in the general amnesty of June 1917.

Ashe immediately became active in reorganising the Volunteers and was elected president of the IRB. But within a month a warrant was issued for his arrest following a speech he made in Ballinalee, County Longford, on 25 July. He was arrested in Dublin on 18 August and taken to the Bridewell.

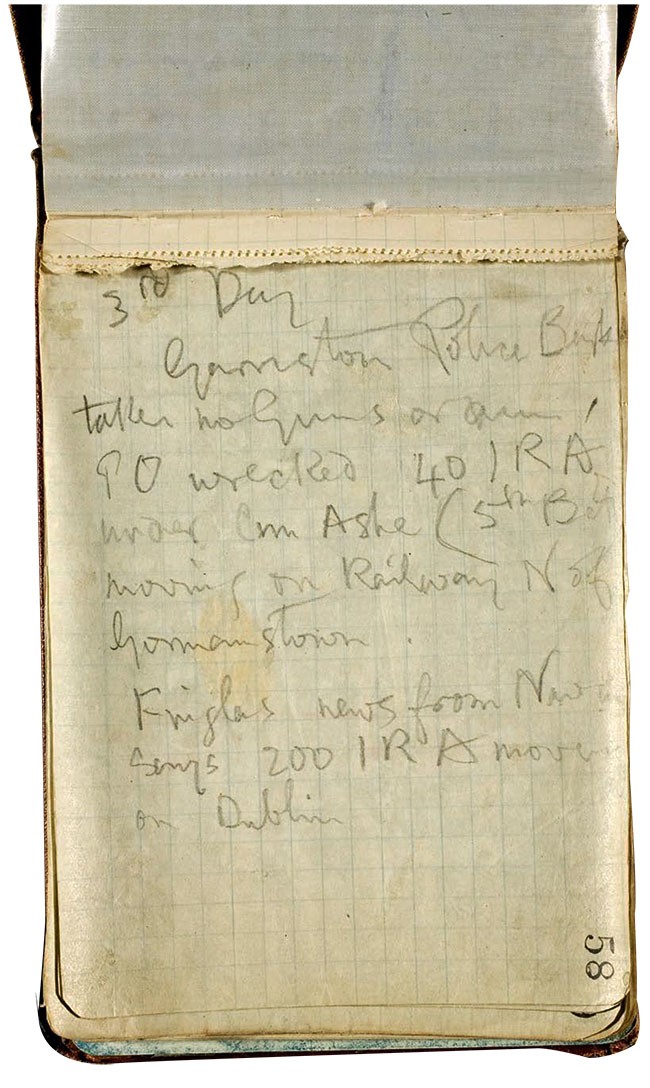

•Battle of Ashbourne – A note from Joseph Plunkett’s field notebook about the action in County Meath

His trial, over eight days, took the form of a court-martial in Mountjoy Prison, beginning on 3 September. On often-conflicting evidence of the ‘mental notes’ of RIC men, he was found guilty of a charge of “attempting to cause disaffection among the civilian population at Ballinalee by urging them to form military societies, arm and train, and saying that he would call out his men as he did in 1916 if the opportunity arose again”.

Sentenced to two years’ hard labour, Ashe joined some 40 other political prisoners then in Mountjoy. He immediately took the lead in resisting criminalisation and they all refused to do prison work. Ashe refused to obey prison rules, for example, speaking to all he met during exercises.

Two days after sentence, on 13 September, he was warned by the deputy governor to obey regulations but replied that he would not be treated as a criminal.

On 17 September, Ashe was refused a mattress and was forced to sleep on the floor. The same day the political prisoners presented the deputy governor with their demands for political status.

The demands were: free association throughout the day; work of their own choice; separation from non-political prisoners; and to be allowed books, writing materials and more letters and visits.

The political prisoners had decided that if these demands were not met within a fortnight, they would go on hunger strike on 1 October.

On 20 September, Ashe and his comrades were moved to another wing and confined to their cells. Later the same day, warders invaded the cells, assaulted the prisoners and removed everything from the cells down to the prisoners’ boots. In response, it was decided to begin the hunger strike immediately.

Austin Stack, the prisoners’ O/C, instructed them that if force-fed they were not to endanger their lives by resisting but were not to walk to the place where it would take place, insisting on being carried.

In the next few days, word of trouble in the jail spread and crowds gathered outside. On Saturday 22 September, an intervention by the Lord Mayor of Dublin resulted in furniture being returned to the cells. The next day, force-feeding began.

Force-feeding took the form of a tube from a pump being inserted through the mouth or nose into the stomach. The other end of the pump was put into the vessel containing the food which was then pumped into the stomach. The operation lasted about ten minutes and each prisoner was force-fed twice each day. Thomas Ashe was forcibly fed only five times in all.

The last time Ashe was force-fed was at 11:15am on Tuesday 25 September by a Dr Lowe. On the way to the operating room, Ashe said he was well but weak. The tube was put down his throat the wrong way, causing him to cough violently. The tube was withdrawn and put down again.

After eight minutes of force-feeding, Ashe’s lips turned blue and he collapsed. From bruises found on his neck afterwards, it was obvious that his throat had been held tightly throughout.

At 12 noon, Ashe was taken to the prison hospital where his pulse was found to be weak, his breathing laboured and his temperature low. Five hours later, Thomas Ashe was transferred to the Mater Hospital.

As the evening progressed, Ashe grew weaker and doctors predicted his imminent death. He told the two Capuchin priests who visited him, Fr Albert and Fr Augustine:

“I was splendid in the morning until forcibly fed. This forcible feeding upset me completely.”

The priests administered the Last Rites and Ashe, deteriorating rapidly, died at 10:30pm. The heavy British Army guard left the hospital and the Irish Volunteers from Fingal moved in, mounting a guard of honour over the body of their dead leader, now dressed in his Irish Volunteer uniform.

• A volley is fired over the grave of Thomas Ashe in Glasnevin

When news of his death reached the jail, his comrades expressed renewed determination to carry on the hunger strike until all their demands had been conceded.

Force-feeding continued until the day before Ashe’s funeral when the Lord Mayor of Dublin visited Austin Stack and told him that the authorities would treat the prisoners as prisoners of war.

Ashe’s body was removed to Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral and after a Requiem Mass was taken to City Hall, where it lay in state surrounded by an armed guard of Volunteers as thousands filed past to pay their last respects.

On Sunday 30 September, people came from all over Ireland to attend his funeral which left City Hall at 12 noon. The coffin was draped in the Tricolour and accompanied by its guard of honour. It was followed by thousands, including the Lord Mayor and the Archbishop of Dublin, and took four hours to reach Glasnevin Cemetery.

The coffin was carried to the graveside by six former political prisoners. After prayers and a short silence, three volleys of shots rang out as a final salute to the dead soldier. A Fianna Éireann bugler sounded The Last Post. Michael Collins delivered the shortest of orations:

“The volley you have just heard fired is the only tribute necessary over the grave of a dead Fenian.”

The coroner’s jury, 11 days after Ashe’s death, declared, in accordance with the medical evidence, that Thomas Ashe’s death had been caused by the treatment which he suffered in jail. The jury censured the British authorities and the deputy governor of the prison and it condemned forcible feeding as an inhuman and dangerous operation.

But many more Irishmen were to die on hunger strike in the next 64 years.