1 June 2017 Edition

Mayo’s heroes

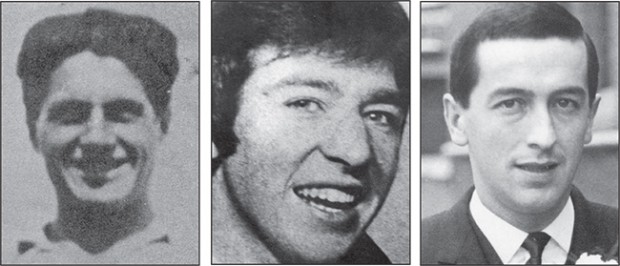

• Seán 'Jack' McNeela, Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg

The National Hunger Strike Commemoration takes place in the home county of Seán 'Jack' McNeela, Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg on Sunday 13 August – main speaker former hunger striker Gerry Kelly MLA

GEORGE STAGG and his wife Mary were laughing with Senator Rose Conway Walsh in the corridors of the Sinn Féin offices in Leinster House when they met to talk about the upcoming National Hunger Strike Commemoration in their native County Mayo.

Rose’s confinement to a wheelchair after an Achilles tendon operation hadn’t stopped her coming up from the West and freewheeling around the sixth-floor offices in Dublin but navigating the meeting room packed with chairs was causing some juggling and chuckling.

When we sat down to talk about Frank, however, George’s chin dropped to his chest, his fingers drew invisible circles on the table and his eyes welled up with tears at the memory of his older brother’s life and death in the republican cause. Mary would reach out and touch his arm and George would pick up again, smile and recall the character that was Frank, radiating his brother’s sense of fun, pride and determination.

“He never doubted himself,” George said, shaking his head vigorously. “Never doubted his cause.”

George is a brother of IRA Volunteer Frank Stagg, from Hollymount, County Mayo, who died in Wakefield Prison, Yorkshire, on 12 February 1976 after 62 days on hunger strike.

Two years previously, on 3 June 1974, another Mayo man, Michael Gaughan, died from pneumonia after a force-feeding tube pierced his lung in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. He was only 24 years old.

They followed in the tradition of Mayoman Seán ‘Jack’ McNeela, who died on 19 April 1940 in Arbour Hill Military Detention Barracks, Dublin, after 55 days on hunger strike along with his friend and comrade Tony D’Arcy from Galway.

Jack McNeela’s story played a big part in raising Rose Conway Walsh’s awareness of her county’s proud republican history as both are from Ballycroy. Mayo’s place in the fight for freedom was to also capture the imagination of young Proinsias Stagg.

(“He was always called Proinsias at home but the British couldn’t pronounce Proinsias,” Mary explained, so Frank is used a lot.)

• Frank's wedding and Frank's mother and Mary stand at the Fine Gael/Labour grave shortly after his burial

George recalled that their father, Henry, an IRA veteran of the Tan War and Civil War wounded in the shoulder on active service, used to gather his sons and daughters around and tell them stories about the past and read to them from books.

“This was at the same time as his old comrades used to call to the house and they’d go off to one side of the house to have secret talks,” George recalled with a knowing smile and a wink.

Frank was born in 1942, the seventh of 13 children (seven boys and six girls).

George recalled that he was “a small man, five-foot-six, with jet-black hair and a dark complexion and a great sense of humour”.

After he left school, Frank worked as an assistant gamekeeper with his uncle at Ballynahinch Castle in Connemara. “He was mad into game shooting and fishing,” George said. “The money probably wasn’t great but he thoroughly enjoyed the work.”

Frank was also fond of Gaelic football, handball and singing. “He was a good singer but he wasn’t as good as he thought he was,” George laughed. “He thought he was a great singer.”

He would sing rebel songs and old Irish ballads, even penning a song or two himself, One he'd titled ‘The Hollymount Queen’ and included the names of as many neighbours as he could manage, Mary said.

His passion, though, was politics. Frank and his father with his republican background were “both very much of the same mind”, George recalled.

England

Frank, like countless others, had to emigrate to find work, seeking employment in England, where the Staggs had relatives, particularly in Coventry.

In England, Frank worked as a bus conductor and later qualified as a bus driver. In 1970, he married Bridie Armstrong from Carnicon, County Mayo.

He joined Sinn Féin in Luton in 1972 and shortly afterwards joined the IRA.

George and Mary recalled that as soon as the conflict in the Six Counties erupted with the suppression of the Civil Rights Movement by the RUC, B-Specials and the Unionist Party regime running the ‘Orange State’, Frank became active in fund-raising for holidays in England for children from the North.

Frank remained in touch with home and spent his annual holidays in Hollymount up to the year of his arrest and imprisonment in 1973. In the words of his mother, Mary: “He never forgot he was Irish.”

• The handball Frank played with to All-Ireland level, winning Mayo and Connacht Minor Championships; his lighter and penknife; and an armband worn at a commemoration in New York after his death

And Mary never forgot her son.

Mary regularly undertook the arduous journey from the west coast of Ireland, across the country and the Irish Sea to the various prisons all over England Frank was held in. And it was all for a half-hour visit after being subjected to a strip-search. It was not unusual for relatives of IRA prisoners, classified as top-security ‘Category A’, to arrive at a prison only to be told then that the prisoner had been moved (“ghosted”, families called it) to somewhere hundreds of miles away.

Frank’s mother had to travel to six different prisons to see her son.

She was with him when he died.

“Mother was very strong,” George recalled. “She stood by him 100%.”

It was a solidarity that was sorely needed.

“Frank was almost always in isolation because he wouldn’t do prison work or wear prison uniform,” George said. “He was constantly in dungeons, down below decks. Filthy holes with lice.

“He just wouldn’t give in. His spirit was good, even when he wasn’t well physically.

“Never was there any question that he was an Irish republican and therefore a political prisoner.”

When Michael Gaughan died, Frank was “devastated”, George said.

Even though the two IRA men were from Mayo (Gaughan was from Ballina), they hadn’t known each other before meeting in prison and having adjoining cells.

“Michael was very staunch but he wasn’t from a republican background,” George noted and added: “He was an outstanding young man.”

Because Michael was being force-fed during his hunger strike, his death took everyone by surprise.

During force-feeding, the prisoner was seated on a chair and held down by the shoulders and chin. A lever was pushed between the teeth – by brute strength if the prisoner resisted, as they often did to the best of their ability – to prise open the jaw and a wooden clamp shoved into the mouth to keep it open. (It was this treatment that broke Frank's teeth, Mary said.)

A thick, greased tube was then put through a hole in the clamp, thrust down the throat and into the stomach. Often the tube would go into the windpipe and have to be withdrawn. During this procedure the victim would be constantly vomiting.

Broken promises

Following the death of Michael Gaughan as a result of the force-feeding, the remaining hunger strikers ended their fast after assurances from the prison authorities that they would be transferred to a prison in Ireland.

The assurances were to join the list of broken promises.

A month after the death of Michael Gaughan, Frank was moved from Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England, to Long Lartin in Worcestershire, in the midlands.

There, on 10 October 1974, Frank once more resorted to a hunger strike because he had not been transferred to Ireland and because he and his relatives were being subjected to degrading searches before and after visits.

All his visits were stopped, although his mother was allowed a brief visit on 26 October. Thirty-one days into the hunger strike, he was told that his demand for repatriation would be met and he ended his hunger strike.

Price sisters, Hugh Feeney, Gerry Kelly

In March 1975, Dolours and Marian Price were transferred to Armagh Jail and, in April, Hugh Feeney and Gerry Kelly (the main speaker at this year’s National Hunger Strike Commemoration) were moved to Long Kesh.

But Frank Stagg remained imprisoned in England. By this time he was in Wakefield, where he was being kept in solitary confinement because he refused to do prison work.

On 14 December 1975, Frank went on hunger strike once again. His demands were for an end to solitary confinement and no prison work pending transfer to a prison in Ireland (Long Kesh).

This time any promises from the authorities would have to be given in writing.

But Frank knew this would be his final hunger strike – “one way or another”, George told Rose Conway Walsh.

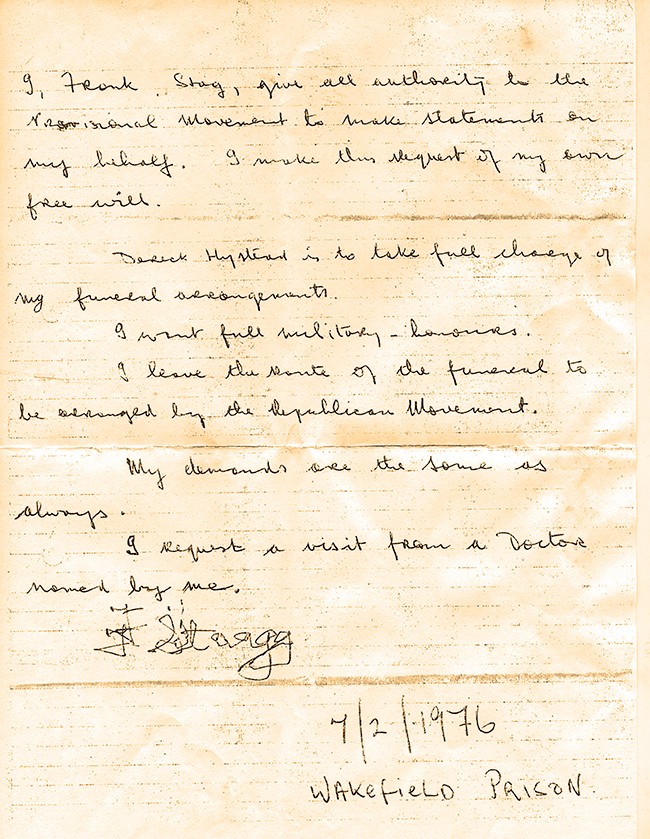

George was with Frank in the days before he died, when Frank dictated to George a codicil to his will about wanting a republican funeral with IRA military honours, assigning responsibility for his burial arrangements to Derek Highstead, then Sinn Féin National Organiser in Britain.

Mary recalled that Frank was “wasting away, taking little, short breaths” but he was still determined, George said.

“Frank led that process. He called out what he wanted and then he signed it, ready for if the worst came to the worst.”

Frank’s funeral arrangements had been brought up before.

“He knew where he was going, he knew where this was headed.”

Frank had an outside hope that the Irish Government would put pressure on the British Government to agree a transfer to Long Kesh even though it was, as George said, “a vicious, vindictive, anti-republican, real Blueshirt government”.

Frank was under no illusions about what might happen though. Nevertheless, he was unwavering.

“He knew that this hunger strike was his last hunger strike, either way – he either got what he wanted or he would die.

“He wasn’t going to come off the hunger strike until he had been moved, not just told again he was going to be moved.

“This was the end; his last hunger strike.”

Frank remained committed to his principles and, after fasting for 62 days, died on 12 February 1976.

• Further reading: Special Category – The IRA in English Prisons, Volume 1, 1968-1978, by Ruan O’Donnell

• Mary and George Stagg

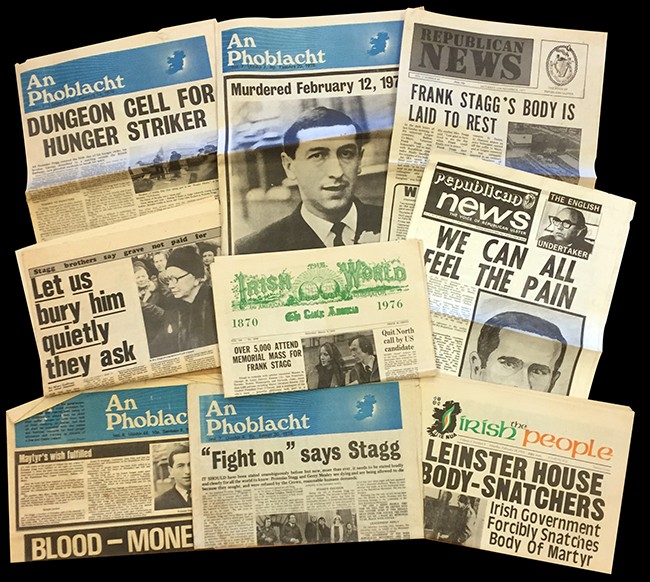

Frank Stagg’s body hijacked by Fine Gael/Labour Government

• Frank's instructions for his funeral to be a republican one with full IRA honours

THE remains of Frank Stagg were on the way to Dublin by air when the Government in Dublin, to prevent a display of republican sentiment such as accompanied the funeral of Michael Gaughan two years previously, diverted the plane to Shannon Airport.

Armed Garda Special Branch men seized the coffin and locked it in the airport mortuary.

The following day, Frank’s coffin was airlifted by helicopter to Robeen Church at Hollymount in County Mayo.

On Saturday 21 February, a private Requiem Mass was held and his body was taken to Ballina, where it was borne by Special Branch men to a grave in an isolated corner of Leigue Cemetery, some distance from the Republican Plot where he had asked to be buried. In the hope of preventing a transfer, six feet of cement was afterwards placed on top of the coffin.

On the Sunday, the Republican Movement held its ceremonies at the Republican Plot. A volley of shots was fired and a pledge made that Frank Stagg’s body would be moved to the Republican Plot in accordance with his wishes.

For six months there was a permanent 24-hour Garda presence in Leigue Cemetery but eventually it was lifted. On the night of 6 November 1976, a group of IRA Volunteers, accompanied by a priest, dug down in an empty plot beside the grave (presciently purchased for £5 by George Stagg at the time of Frank’s burial), tunnelled under the cement and removed the coffin.

After a short religious service they reinterred the remains of Frank Stagg in the Republican Plot, beside Michael Gaughan.

• Troops and gardaí in riot gear take over the streets of Ballina