2 May 2017 Edition

Partition and the South Longford by-election

Remembering the Past

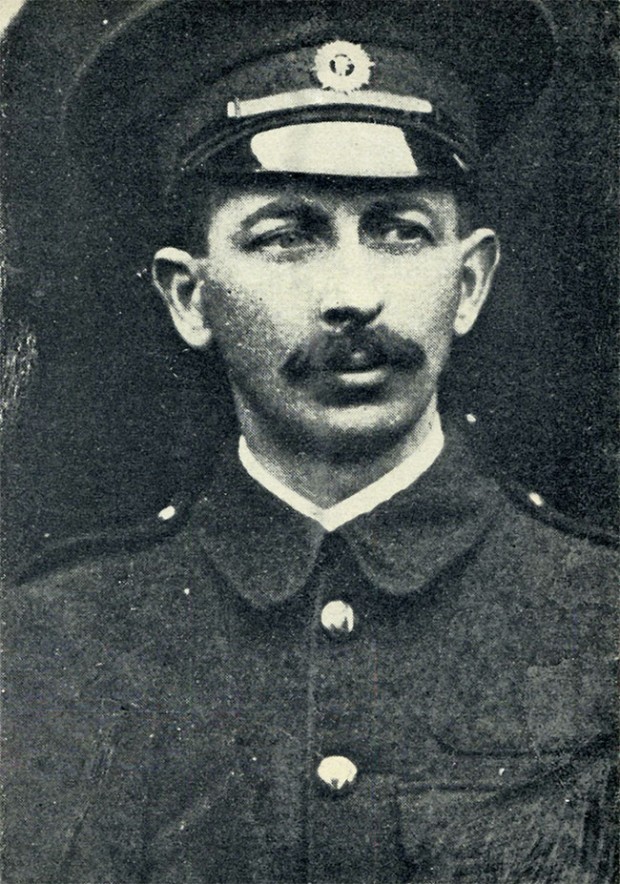

• Joseph McGuinness in Volunteer uniform

The South Longford by-election of May 1917 is principally remembered as one in which a republican prisoner was elected on the slogan “Put him in to get him out” but equally important in achieving a republican victory at the polls was the renewed threat by the British Government to partition Ireland.

David Lloyd George had become British Prime Minister in December 1916. Earlier that year, in the wake of the Rising, he had assured unionists that, if the suspended Home Rule Bill became law when the First World War was over ,the unionist-dominated North-East of Ireland would be excluded. The partition of Ireland had first been proposed by the British Government in 1914. Three years later, in early 1917, Lloyd George raised once more the prospect of what James Connolly had called “dismembering Ireland”.

The British Prime Minister was playing a double game. The United States was about to enter the First World War on the side of Britain and France. To help ensure full American commitment Lloyd George wanted to placate opinion in the US which was critical of British repression in the wake of the Rising.

In a speech in the House of Commons on 7 March he admitted that “centuries of brutal and often ruthless injustice” had driven “hatred of British rule into the very marrow of the Irish race”. He spoke of Home Rule before the war ended – but only for “that part of Ireland that clearly demands it”. To placate the Conservatives and unionists in his Cabinet, he said that to place the north-eastern counties “under national rule against their will” would be “an outrage”.

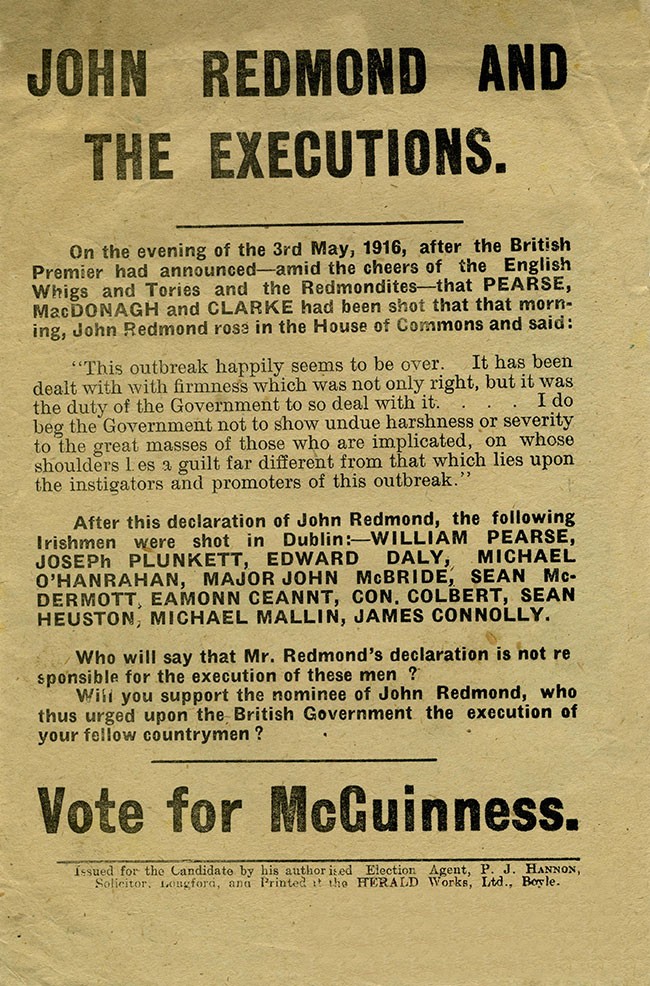

Back in 1914, John Redmond and his Irish Parliamentary Party had agreed to the idea of some temporary form of partition but now, under pressure after the Rising, the executions and the jailing of hundreds of nationalists, and having lost the Roscommon by-election to Count Plunkett, the Redmondites walked out of the House of Commons in protest against Lloyd George’s speech.

It was in this context that a vacancy occurred for the constituency of South Longford. It was a stronghold of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Following the victory of Plunkett, some saw South Longford as another opportunity to defeat Redmond and advance the ideals of the 1916 Rising. Others were cautious, at least initially, including Eamon de Valera, then a prisoner in Lewes Jail in England, who feared a setback at the polls. A fellow Lewes prisoner, Thomas Ashe, argued that a prisoner candidate should be put forward.

The bold move of standing a prisoner candidate was in line with the growing militant mood in Ireland. The anniversary of the Rising had been commemorated in spite of British military repression. Prosecutions for meetings, speeches, displaying the Tricolour and singing rebel songs were commonplace and freedom of the press was non-existent. Many republicans were still in English prisons such as Lewes and Aylesbury, where Constance Markievicz was held. Following his release from Frongoch Internment Camp, Michael Collins was emerging as a leader and he was a prime mover in having Lewes prisoner Joseph McGuinness nominated to stand in South Longford.

At Easter 1916, McGuinness had fought in Commandant Ned Daly’s First Battalion in the Four Courts area. Originally from Roscommon, he worked in the United States and in Longford before opening a drapery business in Dublin. His ten-year sentence by the court martial had been commuted to three years. A convinced separatist, McGuinness opposed the idea of contesting the election but was nominated anyway.

The Redmondite candidate described Sinn Féin as “a self-destructive policy advocated by men who were never known to do a day’s work for Ireland”.

West Belfast Redmondite MP Joe Devlin said the issue was “whether they were in favour of a self-governed Ireland or a hopeless fight for an Irish Republic”. John Dillon, reflecting how far the Redmondites had gone to embrace the Empire, said the choice was self-government with “a continued connection with Great Britain” or “an Irish Republic and complete separation from the British Empire”.

On the eve of the poll, a manifesto against partition was published and signed by three Roman Catholic archbishops and 15 bishops, three Protestant bishops, as well as county council chairs and other public figures. The manifesto declared:

“To Irishmen of every creed and class and party, the very thought of our country partitioned and torn as a new Poland must be of heart-rending sorrow.”

In such a close election this was a decisive intervention. Polling day was on 9 May and Joe McGuinness won by only 37 votes. He won despite an outdated electoral register, the local strength of the Redmondite party and press hostility.

The Times of London described it as “a most damaging defeat” for the Redmondites and added that “no settlement based on the temporary or permanent partition of Ireland can have the smallest chance of success”.

The Irish Times said the partition proposal was now “dead as a doornail and any government which should try to resurrect it would show itself incredibly ignorant or insanely contemptuous of the solitary conviction which now unites all political parties in Ireland”.

Tragically, the British plot to partition Ireland was not dead and would be revived by Lloyd George three years later. In May 1917, though, republicans celebrated the South Longford election victory and the British government contemplated what the Manchester Guardian described as “the equivalent of a serious British defeat in the field”.