5 September 2016 Edition

From the H-Blocks to Robben Island

• Laurence McKeown on Robben Island

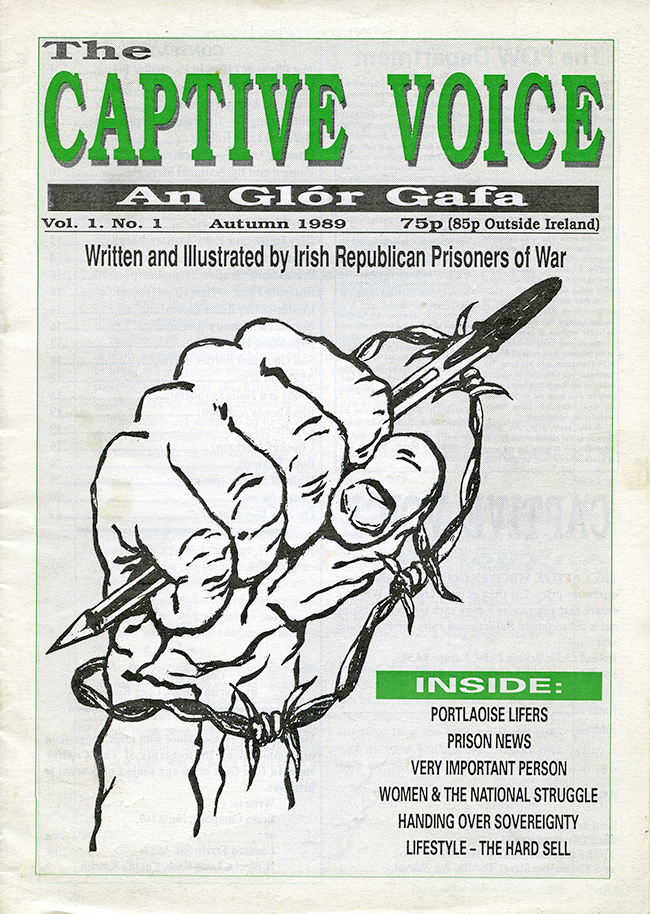

The magazine written entirely by republican prisoners in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh had to be smuggled out to An Phoblacht for printing

Hunger Striker Laurence McKeown’s play 'Those You Pass on the Street' moved people to tears during the National Arts Festival in South Africa

AN GLÓR GAFA/The Captive Voice, the magazine written entirely by republican prisoners, was formally established in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh in 1989.

It was compiled and edited within the H-Blocks but was contributed to by republican prisoners wherever they were held: Armagh Women’s Prison, Portlaoise, prisons in England, Europe, and the United States. In the early years all the material for publication had to be smuggled into the prison, the edition compiled and edited, then smuggled out of the prison where Sinn Féin’s POW Department passed it on to An Phoblacht for printing. In later years we were able to produce the magazine openly through the prison authorities. Five thousand copies of each edition were printed and over the next ten years there was a total of 26 editions.

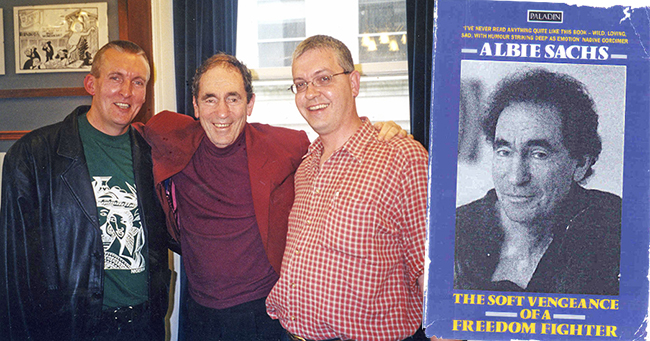

In one edition we published a review of the book written by Albie Sachs, The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter (1990). Albie was a member of the African National Congress (ANC) who the apartheid regime attempted to kill in 1988 in Maputo, Mozambique, where he was living in exile. A booby-trap car bomb exploded, resulting in the loss of his right arm and the sight in one eye. Years later, when he returned to an apartheid-free South Africa, Nelson Mandela appointed him a judge in the new Constitutional Court, charged with drafting a charter for a new non-racial state. Sachs became a persuasive advocate for the inclusion of a Bill of Rights and an independent judiciary in the new constitution and as a judge he also made a number of landmark rulings, including recognising gay marriage.

In his book, Albie spoke in very personal and moving terms about his life, the experience of being injured in the bomb blast, and of his recovery afterwards. It was at a time in our own educational, cultural, and artistic development where we were encouraging prisoners to ‘own their voice’ and about how the ‘personal was political’ and how it was ‘okay’ to write about the personal pain, troubles, and battles we endured as prisoners and activists and not just the tales of commitment, perseverance, and endurance.

There was one sentence in Albie’s book that totally jarred with us. He referred to the “sectarian bombing campaign of the IRA”. We found it strange that someone involved in a revolutionary movement such as the ANC could make such a remark. We wondered if it came from the many years he had spent in London studying, where he would have been exposed to a hostile British media and with little contact with the Irish struggle.

We wrote a letter to Albie in which we expressed dismay that he would make what appeared to us as a throwaway remark about the IRA armed struggle. We also praised his book and the work he was engaged in and included a copy of our review.

The letter was smuggled out of the prison and later hand-delivered to him by a comrade who was part of a youth delegation trip to South Africa. And that was the last we heard about it – until 2003 when Albie visited Belfast.

I was working with Coiste na nIarchimí at the time (the umbrella organisation for former IRA prisoners) and we had regular meetings with the Community Foundation (CFNI) as they handled the EU funding for ex-prisoner groups under the Peace and Reconciliation programme.

• Laurence with Albie Sachs and Mike Ritchie

Albie spoke at an event organised by CFNI where he was to present to them two copies of the new Bill of Rights for South Africa, which he had been heavily involved in drawing up. In the course of his speech he referred to the letter he had once received from prisoners in Ireland and how it was one of his big regrets that he had never responded to it or didn’t know who to respond to. As he continued to speak I silently signalled to Avila Kilmurry, the CEO of CFNI, that it was me who had sent the letter. When he had finished his address, Avila took the microphone and said: “We didn’t plan it, Albie, but I can tell you that one of the prisoners who sent you that letter is in the audience this evening.” I walked over to him, shook hands, and we embraced. Later, Mike Ritchie (then Co-ordinator of Coiste) and I had a long conversation with him.

Fast-forward to early July of this year when I visited South Africa.

I was there because the most recent play I wrote, Those You Pass on the Street, produced by Kabosh Theatre Company, Belfast, was selected as part of the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown – the largest and oldest arts festival in South Africa. This year South Africa sees a number of anniversaries: the 20th anniversary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; the 40th anniversary of the Soweto Uprising; the 65th anniversary of the signing of the Freedom Charter; and others.

As part of the theatre section of the festival programme (which also included film, music, dance, performing arts, visual arts, and discussion and debate), there was a focus on the theme of ‘dealing with the past’ and looking at how various countries had approached this. They also wanted to look at the role the arts had played in that process.

Those You Pass on the Street was the only play chosen from Ireland. It was performed five times over three days to packed audiences. Each performance was followed by a Q&A with the Artistic Director of Kabosh, Paula McFetridge, and myself.

Some of the contributions made during the Q&A were very emotional. In the evaluation sheets we left for audience members to fill in one person commented: “I found myself crying. I’m not sure what started it, but I felt such heartache.” Others welcomed the opportunity to start a discussion: “Very powerful . . . opening a conversation rather than closing it.” And many saw the parallels between what had happened in Ireland and in South Africa: “The play cleverly provides a nuanced view of the 30-year British colonial war in Northern Ireland . . . Like our own situation, it’s complex” (Nigel Vermass, Cue Magazine, South Africa).

• Stage technician James Kennedy, actors Ciarán Nolan, Vincent Higgins and Carol Moore, Albie Sachs, Laurence, and actor and artistic director Paula McFetridge

On the night of the last performance, just as Paula and I were about to bring the Q&A to a close, a man got up from his seat in the second row of the audience and walked towards me. Paula was startled. She was off to my side and had seen this man with the right sleeve of his jacket apparently empty and hanging limp by his side, his right hand seemingly inside the jacket, walking in my direction. She feared it was someone going to pull a weapon to attack me. But from where I sat, as soon as he stepped into the light of the stage, I could clearly identify the man coming towards me – it was Albie Sachs. He walked over to me, I stood up, he embraced me warmly then turned to the audience and said, “I’m Albie Sachs and I’ll let Laurence describe to you how we met.” The audience burst into applause.

I related the story about the review of his book, of writing to him, and of later meeting in Belfast. Albie then spoke of our letter to him from the H-Blocks and about our discussions in the prison at the time about republicans opening up to tell the personal story of struggle. He said:

“I think they were debating whether or not it was okay for freedom fighters to cry. I have cried many times after watching a film but very rarely after attending a play. I have to say that tonight I cried at the ending of your play. Those closing lines are the most powerful I have ever heard and the most appropriate way for your play to end.”

The cast of the play then went on to Rwanda to perform again as part of the Ubumuntu Arts Festival at the site of the monument to the victims of genocide in that country. Again, the response to it was overwhelming. Kabosh had not received enough funding to allow me go accompany the cast to Rwanda but that provided me with the opportunity to fulfil a lifelong ambition and travel to Cape Town to visit Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela and his comrades had been imprisoned for so many years.

The ferry to the island takes about 30 minutes. Our tour guide on the bus, Thabo, was excellent. He told us not only the history of the island but also of South Africa and of the legacy of colonialism. He also told us of the Irish missionaries and nuns who came to the island to work with the leper community that had been banished from the mainland and how a part of the island is now named “The Irish Village”.

The bus stopped at the quarry where Mandela and the other prisoners worked. We were told of the damage done to their eyes with the sun reflecting off the white limestone and how the dust from the quarry had got into their lungs, causing permanent damage.

• Laurence McKeown with tour guide and former political prisoner Itumeleng Makwela on Robben Island

Thabo then pointed to a cave in the quarry wall and told us that the prisoners used it to eat their lunch in but it was also the place they had to use as a toilet. They were under dire warnings that any attempt to leave the confines of the quarry, even for toiletry purposes, would result in them being shot. They had to endure the smell of the cave while they ate their lunch. It also meant that the guards did not enter the cave because of the smell. This provided the prisoners with the opportunity to discuss freely amongst themselves in a way they could not do back in the prison. It reminded me very much of our own discussions and debates in the H-Blocks during the ‘No Wash Protest’ and the extreme physical conditions those discussions took place in.

When we eventually arrived at the former prison we were introduced to the tour guide for that part of the tour. Itumeleng Makwela, a former political prisoner, told us of being on hunger strike for several days but how, even during that time, he had to work in the kitchens, cooking and delivering meals. He showed us around the various cell-blocks and where Mandela was held. As the tour ended, I introduced myself to Itumeleng and told him of being in prison in Ireland. He said: “I was wondering who was wearing the Bobby Sands T-shirt!” I asked one of the other people on the tour, an American, if they would take a photo of us. As I handed her my camera, Itumeleng pointed to my T-shirt and asked her: “Do you know who this man was? Bobby Sands?” She shook her head. “He was an Irish freedom fighter.”

We returned from South Africa and Rwanda and the play then went on tour in west Cork as part of the Fit-up Festival. As I travelled by ferry over to Bere Island I thought of the ferry to Robben Island. I thought of writing this article and of that Sunday afternoon in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh when we established An Glór Gafa/The Captive Voice and of how we ‘found our voice’ and continue to let it be heard.

One sentence from the first editorial of the magazine is particularly poignant in this year, the 40th anniversary of the start of the Blanket Protest:

“Through individual and collective struggle and sacrifice, the idea of gaol as a breaking yard has been thrown back in the faces of those who imprison us.”

Very true.

In the dying words of the poet Seanchan: “Dead faces laugh, King! King! Dead faces laugh.”