15 August 2016

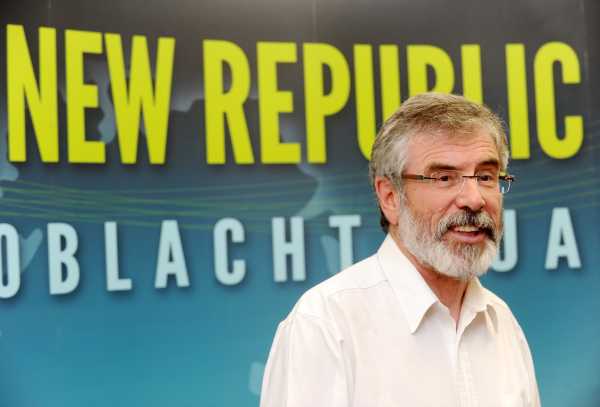

Time to talk about Irish unity

THE ISSUE of Irish unity has been absent from Official Ireland’s centenary celebrations to mark 1916.

There have been parades and TV specials, and books written and reams of newspaper articles published. There are some excellent exhibitions and songs of the period have been sung and debates held.

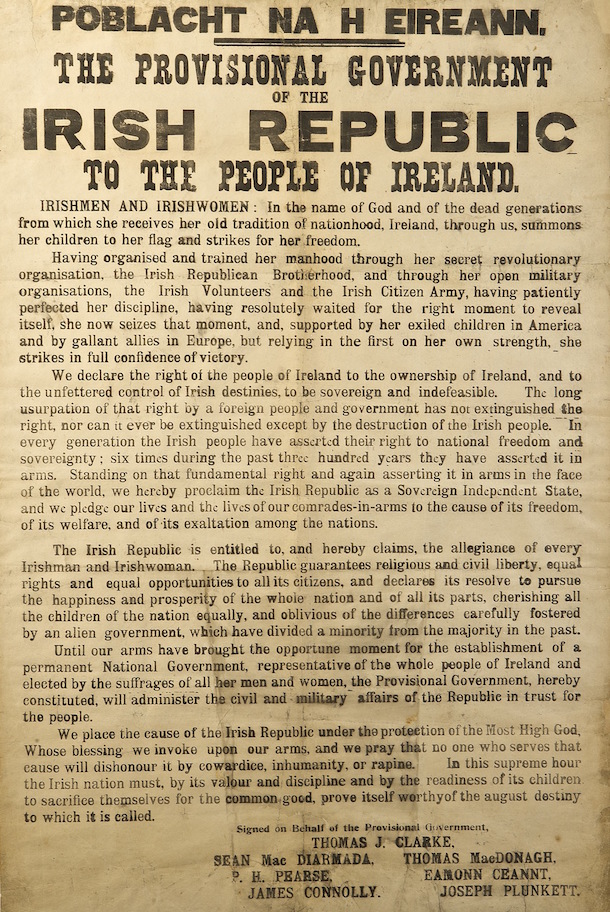

But the fracture of the island by partition – the abandonment of the 1916 Proclamation as a declaration of freedom and justice for all of Ireland – has been ignored.

The Republic envisaged by the leaders of 1916 and by the Proclamation was to be a rejection of all that was bad and divisive and elitist in British imperialism and colonisation.

It was to be an Ireland of equal citizens. A Republic for all.

Today, those of us who desire that outcome are told by some that we are being divisive. We are told that there will be a united Ireland at some undefined time in the future. But it will not happen through wishful thinking or sitting in a bar singing songs (not that there is anything wrong with singing songs of freedom) or simply talking about it.

It needs a political strategy with clear objectives and actions.

Those who advocate the wishful thinking approach to Irish unity point to the enhanced relationships between London and Dublin. They raise and praise the ‘special’ relationship between the Irish and British governments as evidence of change. And while it is true that much progress has been made, the reality is that the British Government has failed to honour key commitments within the Good Friday and other agreements.

It has unilaterally set aside elements of the various agreements, with barely a whimper of protest, especially from the Irish Establishment.

It has failed to deliver on a range of important issues, including:-

- A Civic Forum in the North

- An All-Ireland Civic Forum

- A Bill of Rights for the North

- Joint North/South committee of the two Human Rights Commissions

- An All-Ireland Charter of Rights

- Honouring its obligations in compliance with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- The introduction of Acht na Gaeilge

The British have also obstructed efforts to resolve the legacy of the past by refusing to honour its commitments under the Haass agreement, failing to provide information on the Dublin/Monaghan and Dundalk bombs, and reneging on its Weston Park commitment on an inquiry into the murder of human rights lawyer Pat Finucane.

The real ‘value’ of the special relationship between the Irish and British governments was demonstrated in the recent Brexit campaign.

It is clear the economic interests of the island of Ireland are collateral damage in a fight between factions of the right-wing of British politics.

The implications of Brexit are becoming increasingly apparent: a real threat to the economy, barriers to trade, a possible EU frontier across Ireland and a fundamental crisis in North/South co-operation.

At no time in the Brexit debate was the impact on Ireland, North or South, considered. Our national concerns were dismissed.

The people of the North voted against Brexit. Just as they did in the Good Friday Agreement referendum, all sections of the community – republican and unionist – voted in the best interest of all. They voted to remain in the EU. Yet the British Government have said they will impose a Brexit on the North against the expressed will of the majority.

The economies, North and South, are interlinked and interdependent. It has been estimated that 200,000 jobs depend on all-Ireland trade. A recent report on economic modelling of Irish unity demonstrated a dividend and growth in a united Ireland.

The aftermath of the Brexit vote is a clear demonstration of the injustice of partition. It is fundamentally undemocratic and economically wrong.

Partition makes no sense – yet it continues.

A mechanism exists to end partition and bring about Irish unity.

The Good Friday Agreement was voted for by the vast majority of people across Ireland. It is worth remembering that 94% of people in the South and 74% of people in the North voted in favour of the agreement – an Agreement that included a peaceful and democratic pathway to Irish unity.

It provided for concurrent referendums North and South to deliver Irish unity. It obliged the two governments to legislate on the basis of referendums for Irish unity.

National unity is in the national interest. Wishful thinking will not bring about unity. We have a mechanism to achieve unity. We need all of those in favour of unity to act together to bring it about.

This is the time to plan and to build the maximum support for unity. The leadership of those parties which support Irish unity, acting together, could be the leadership which delivers it.

Eighteen years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, we should not need to convince the leaders of Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael to become persuaders for Irish unity.

● Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil leaders Enda Kenny and Mícheál Martin at a 1916 Easter Rising Centenary Commemoration Ceremony

The Irish Government should have a plan for unity.

A first step in the next term of the Oireachtas would be the development of an all-party group to bring forward a Green Paper for Unity.

In addition, we need to develop plans for an all-island health service; for public services in a united Ireland through a united Ireland investment and prosperity plan.

The New Ireland Forum in its time created a space for discussion on constitutional options of change and developed a comprehensive economic options paper on the cost of partition.

It failed because it excluded Sinn Féín and operated at a time of a British veto on change. It was a veto, given voice by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher with her “Out, out out!” rejection.

Thatcher is gone – and so is the British veto.

Constitutional change is in the hands of the people of Ireland, North and South.

The politics of exclusion failed and Sinn Féin is jointly leading government in the North.

We have the opportunity to end partition and build support for a new and united Ireland: a new Ireland that is built on equality and which is citizen-centred and inclusive.

The shape of that new Ireland remains to be drawn.

Now is the time for all parties who support Irish unity to come together to design the pathway to a new and united Ireland.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures