9 August 2017

9 August 1971 – Internment without trial imposed by unionist government

Relying on hopelessly outdated lists containing 450 names provided by the RUC Special Branch, the British Army swept into nationalist areas and arrested 342 men

PLACED on the statute books in 1922 in the immediate aftermath of partition by Sir Richard Dawson Bates, interment – the imprisonment of people without charge or trial – was used by successive Ulster Unionist Party regimes in an effort to smash nationalist resistance.

Throughout 1971, the war in the North intensified as resistance to unionist repression grew. It was becoming clear that – after 50 years of misrule, discrimination and blatant sectarianism – the unionist power structure was fractured and so internment, the tried and trusted weapon used on many an occasions by unionists with the full backing of the British Government, was introduced.

In the early hours of 9 August 1971, the British Army launched their internment operation across the Six Counties.

Relying on hopelessly outdated lists containing 450 names provided by the RUC Special Branch, the British Army swept into nationalist areas and arrested 342 men. Key IRA figures on the lists (and many who never appeared on them) were warned before the swoop began. The list included leaders of the Civil Rights movement such as Ivan Barr and Michael Farrell.

Within 48 hours, 116 of those arrested were released; the remainder were detained at Crumlin Road Prison and on the prison ship The Maidstone.

But, as historian Tim Pat Coogan noted in his book The IRA:

“What they did not include was a single loyalist.

“Although the UVF had begun the killing and bombing, this organisation was left untouched, as were other violent loyalist satellite organisations such as Tara, the Shankill Defence Association and the Ulster Protestant Volunteers.

“It is known that [Prime Minister] Faulkner was urged by the British to include ‘a few Protestants’ in the trawl but he refused.”

In fact, the first loyalist internees were not arrested until 2 February 1973.

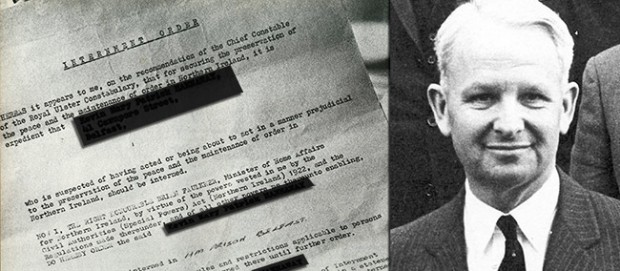

● Internment order and unionist Prime Minister Brian Faulkner

Of the hundreds detained, all were physically abused but 12 were selected for special treatment.

These had been secretly moved from the internment clearing centres to an unknown destination and held for seven days. They had hoods on their heads throughout, had no idea where they were and were kept completely isolated. Their interrogators deceived some detainees into believing that they were to be thrown from high-flying helicopters. (In reality, the blindfolded detainees were thrown from a helicopter that hovered approximately four feet above the ground.)

All were severely beaten, forced to stand spreadeagled against walls until they collapsed, given hardly any food and subjected to ‘white noise’, which prevented them from sleeping. All the while they were constantly interrogated.

This was a new technique of sensory deprivation designed to disorient the mind and facilitate interrogation in-depth.

The order for the removal of the men had been personally signed by Prime Minister Brian Faulkner.

They became known as “The Hooded Men”; they are still pursuing justice for their ill-treatment.

The combination of botched arrests, stories of brutality escaping from the internment centres and the use of internment as a form of communal punishment and humiliation unleashed a wave of anger and resistance across Ireland. This anger took the form of increased support for the IRA and the commencement of a campaign of civil disobedience that enjoyed overwhelming support within the nationalist community in the North.

Ballymurphy in west Belfast was one of the areas to suffer most from the huge military operation that saw over 2,000 British soldiers deployed.

On 9 August, two British soldiers were killed, as were ten civilians, seven of whom were nationalists. After four days, 19 civilians were dead and three British soldiers.

In the two days after internment, eight people from the greater Ballymurphy area were shot dead by the British Army, which had sided with loyalists who were attacking Springfield Park. Among the dead was Fr Hugh Mullan, shot through the heart as he went to give the Last Rites to a young man wounded by British Army gunfire.

As trouble erupted in Ardoyne, loyalists moved out of their houses in the area and torched their homes as they left so that Catholics couldn’t be housed in them. Three people from the area – IRA Volunteer Paddy McAdorey, 16-year-old Leo McGuigan and a Protestant woman, Sarah Worthington – were shot dead by the British Army in the hours after the introduction of internment.

In Derry City, barricades were again erected around Free Derry and for the next 11 months these areas effectively seceded from British control.

● Free Derry resistance

Protests, street demonstrations and riots were common as the entire community sought to demonstrate its opposition to internment.

At the same time, a rents and rates strike was introduced in protest against internment and within weeks was supported by 26,000 households.

A day of action on 16 August saw 8,000 Derry workers on strike. The next day, 30 prominent Derry nationalists withdrew from public bodies. Three days later, 130 non-unionist local councilors across the North withdrew from local authorities.

The IRA held a press conference in Belfast on 13 August at which Joe Cahill, the Officer Commanding the IRA in Belfast, said that internment had had no noticeable effect on IRA structures and the campaign would continue.

In the following months a number of rallies and marches were planned.

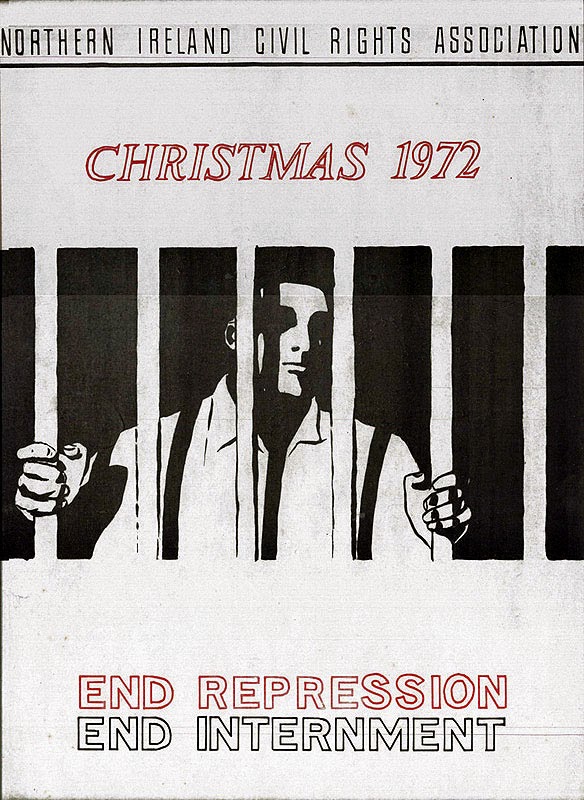

On Christmas Day 1971, 4,000 protesters attempted to march from Belfast to Long Kesh. The march was blocked before reaching its destination on the M1 motorway and dispersed.

On 22 January, another protest march took place at Magilligan Strand, not far from Derry City. This protest was blocked by the British Army and dispersed with violence, in which members of the Parachute Regiment were prominent. (The next anti-internment rally was planned for Derry, on Sunday 30 January 1972 – a day that was to go down in infamy when the Parachute Regiment shot dead 14 people.)

Internment was to continue until 5 December 1975. During that time, 1,981 people were detained – 1,874 were from the nationalist community, 107 were from the unionist community.

Internment without trial was imposed on 9 August 1971.

◼︎ This piece was written by the late Shane MacThomáis and is republished in his memory.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures