1 August 2016 Edition

‘We know where we’re coming from and we know where we’re going to’

Seanadóir Niall Ó Donnghaile, one of the speakers at the National Hunger Strike Commemoration

My generation is growing up in a transformed society, in a different political dynamic because the era of the Hunger Strikes changed things completely

NIALL Ó DONNGHAILE – one of the key speakers at this year’s National Hunger Strike Commemoration – was born in 1985, four years after the H-Blocks Hunger Strike in which ten republican prisoners died in the culmination of the (ultimately successful) fightback against the withdrawal of political status in 1976.

The newly-elected senator in the Oireachtas in Dublin, previously the youngest Mayor of Belfast and a councillor for the nationalist Short Strand enclave in unionist east Belfast, has grown up with the legacy of the struggle in the prisons and on the streets of Short Strand, where he still lives.

It is a legacy that he is mindful of every day in a parliament that elected H-Blocks protesting prisoner Paddy Agnew and Hunger Striker Kieran Doherty as TDs in 1981. Neither of the republican prisoners could take their seats and ‘Doc’ died in the H-Blocks on 2 August 1981 at the age of 25.

“I am a product of the era of the Hunger Strikers,” Niall says with a mixture of sadness, pride, humility and determination.

“In every institution I go into, I think of our patriot dead, the prisoners and their families.”

On the two floors occupied by Sinn Féin’s 30 members of the Oireachtas there are images of 1916 and the H-Blocks Hunger Strikes.

“I don’t need reminding of where we have come from,” Niall says, “but it’s useful for visitors to be reminded because the mainstream media tends to be one-dimensional about Ireland and our history of occupation and partition.”

Niall may have been born after the H-Blocks struggle but he grew up with it all around him.

“In the living room in my house, we had the 1916 Proclamation on one wall and on the other we had the iconic images of the Hunger Strikers.”

And then there are the personal connections.

“My father was in jail with Bobby Sands in Long Kesh; they were in Cage 11.

“My da,” Niall laughs, “said there were times when he could have smashed the guitar over Bobby’s head in the Cages because he wouldn’t shut up playing and singing into the night when all my da wanted to do was sleep.

“We have a telegram to my mother and father on their wedding day from Tomboy [Loudon] and Bobby.

“Then we would have shared all the photos and the stories.”

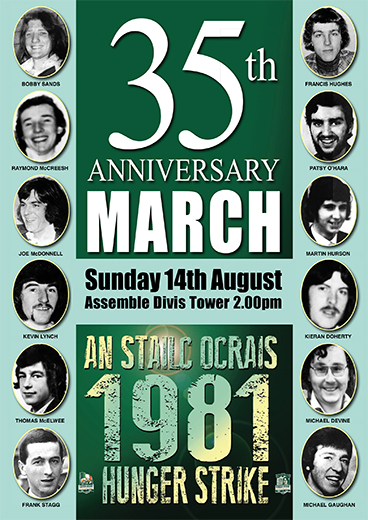

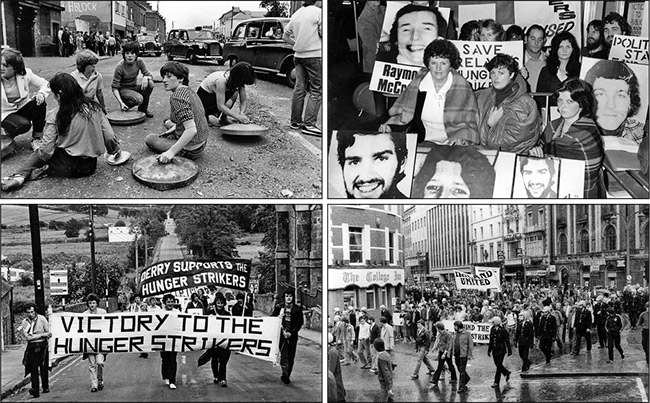

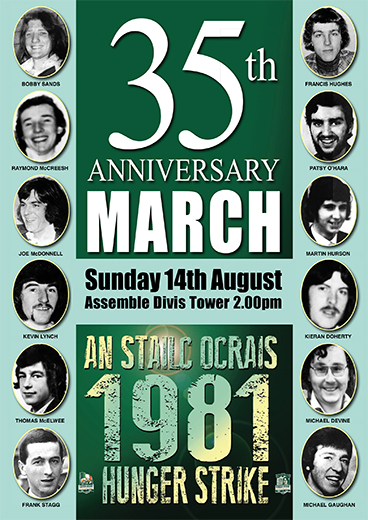

• People all across Ireland and abroad mobilised in support of the Hunger Strikers

Síle Darragh, a neighbour, was imprisoned with Niall’s mother in Armagh. Síle later went on to become OC of the women POWs and, later still, Niall’s first election agent.

“My mother was also in jail in Armagh with Mairéad Farrell, who was on the 1980 H-Blocks Hunger Strike, so she would tell us the stories on their time there.”

Niall’s political adviser in the Seanad is Jim Gibney, who signed Bobby Sands’s by-election nomination and ran Bobby’s election campaign in 1981 with the National H-Blocks/Armagh Committee.

In recent weeks, Niall’s uncle, Seánie McVeigh, passed away. He was a protesting prisoner whose time in jail had taken a terrible toll on a much-loved character.

“Seánie used to tell me about Raymond McCreesh brushing up on his Irish and encouraging Seánie to persevere.

“When you’re stood at the bar in St Matthew’s in the Short Strand and Seánie is telling you about peering through the gap in the cell door and seeing Francis Hughes being pushed up the wing to be taken to the prison hospital, and he has his fist in the air and he’s telling the boys to keep going, that’s something that hits you like a bullet train.

“Kieran Doc from Andytown is another iconic figure for me because I heard all the stories about him from Seánie about the sheer size, spirit and courage of the man,” Niall says with undisguised admiration.

“Seánie said the Screws were terrified of Big Doc and I’m sure there’s a few heads here in Leinster House would have been terrified of him had he got to take his TD’s seat here – he would have shook this place up.”

• Niall’s uncle, Seánie McVeigh, pictured in June 2002 in Short Strand shortly after barriers were erected to protect residents from a loyalist siege

Niall recalls going to the commemorations for the Hunger Strikers, including rallies at Dunville Park, and the streets lined with black flags in memory.

Now there are new ways to keep alive the memory and the legacy of the Hunger Strikers, Niall believes.

There is, of course, the day-to-day hard work of still trying to transform society. There is also, alongside that, the promotion of the republican ideals epitomised by the Hunger Strikers’ selfless sacrifice for their comrades and their people.

“The very first book I picked up for myself outside of school was The Prison Diary of Bobby Sands because it was in the house and I wanted to understand, to learn. It resonated with me; it inspired me, particularly Bobby’s clear grá for the Irish language and how that gave us a great sense of our Irish identity.

“Now Bobby’s writings are on the school curriculum and we have the graphic novel and the new documentary, Bobby Sands: 66 Days.”

Political debates inside Long Kesh and Armagh weren’t just occupational therapy for the prisoners, Niall notes.

“The first naíscoil in the North outside of the Shaw’s Road was in the Strand,” Niall smiles, “set up by Huggie McComb, Philip Rooney and the Cunninghams, all having come through the Cages of Long Kesh and then the Blocks, they started to live that radical notion that republican politics needed to be broader than armed struggle, important as that was at that time.”

Niall Ó Donnghaile regards himself as “in some ways, a direct product” of the struggle waged by the H-Blocks/Armagh generation.

“I’m a product in the republican view that I am a citizen,” he explains, “of being involved in your community, of having a stake in your community, of striving to learn and reinvigorate the Irish language.

“I’m not alone in that,” he hastens to add, reeling off a long list of occupations and roles in the community, “where nationalists of my generation are thriving, growing and sharing the laughter of our children”.

Republicans “are not taking anything for granted”, he says.

“We know where we’re coming from and we know where we’re going to.”

“There’s not a set of eyeballs in these institutions that we cannot look into as proud republicans and say we are here to deliver change, for our communities and for the people whose sacrifices got us this far – the Kieran Docs, the Bobbys, the Maireáds, the Pat Cannons [Niall had spoken that weekend at the 40th anniversary commemoration for the Dublin IRA Volunteer], and all our patriot dead.

“That is important to me. And I’m also appreciative that my generation is growing up in a transformed society, in a different political dynamic because the era of the Hunger Strikes changed things completely.

“We are on the democratic route to national self-determination, so for us to be able to deliver on that we have to be in theses institutions or we leave it to the likes of others – the Fine Gaels or the unionist parties whose histories and ethos are often overlooked or airbrushed by the media.

“We have to change these institutions. I have found that wherever I’ve been – working in Stormont, as Mayor in Belfast City Council or as a senator here in the Oireachtas – republicans change mindsets simply by being republican, by approaching politics in a republican fashion, by treating people in a republican way, from the ministers to the people on the staff at the gate or the canteen who help us do our jobs and make these places work, and with the citizens who put us here to work for them.”

The seanadóir from the Short Strand is sensitive to the symbolism of republicans’ roles in once-reviled institutions, in the corridors of power, previously bastions of privilege or oppression.

“My grandfather was an IRA Volunteer interned in the 1940s. Even though he was a very progressive thinker and very firmly of the Left, his view and that in the house I grew up in generally was that the only decent future for Stormont was to level it after the decades of unionist repression of nationalists that was turned a blind eye to, if not encouraged by politicians at Westminster.

“There is a danger of a narrative that is still trying to be peddled of republicans being responsible for the conflict in the Six Counties – not that it was the product of a sectarian, gerrymandered, one-party police state that suppressed the civil rights movement. That is the Stormont regime that created the society the Hunger Strikers and generations before and after grew up in.

"Now things are changing but republicans are not about airbrushing anyone’s history," he insists.

“There is a new dispensation. All we are doing is demanding equality, and I don’t think that’s too much to ask.

“We are reclaiming Stormont for people, for everyone. We are reclaiming councils for people. We are reclaiming Leinster House for people.

“To me, these are just buildings – it’s the mindsets of the people in these building is what matters in the long run to the citizens outside of the fancy gates of these institutions.

“I think that if we keep on the road of doing what we’re doing we will deliver on the vision of Bobby Sands and his comrades.

“The Hunger Strikers set a very clear example for us. If we can try to live by that republican example then we will get to the type of Ireland that the Hungers Strikers – and all the prisoners and our patriot dead – gave their all for, a free and reunited Ireland.”