11 April 2016 Edition

Smart citizens

• Dortmund an amazing city

Energy saving will reduce a city’s carbon footprint (a good thing) but it will not solve the more pressing ecological, environmental and social issues that every city faces today – not tomorrow

WHEN LIVERPOOL and former Borussia Dortmund manager Jürgen Klopp said confidence is “a little flower that is easily crushed” he was really talking about irony – the kind of irony that produces events that are magnificent in the moment, and are gone in an instant. These days it seems we need these kinds of distractions, magnificent moments that light up our lives, give meaning to our existence and substance to our pitiful futures.

Liverpool and Dortmund are amazing cities – some might even say they are smart cities full of vibrant people – who make stories of their lives into legendary events that sadly are like little flowers – one moment they are there, next they are gone.

Daffodils are resilient flowers of the narcissus genus. Every year, as the natural seasons of winter and spring merge into each other, they sprout up from their perennial bulbs in marginal soil. Municipal authorities like them because they are low maintenance, because they provide colour and because they give the impression that they care about green issues.

Dortmund is one of several cities who have signed up to the EU’s smart city programme. It has a grand desire to be seen as a narcissistic city, pretty as a picture with a synergistic scenario to its energy, food, traffic, transport and waste issues. Given the German predilection for greening cities, towns and villages with sustainable solutions, there is every chance it will succeed. Because Dortmund has smart citizens.

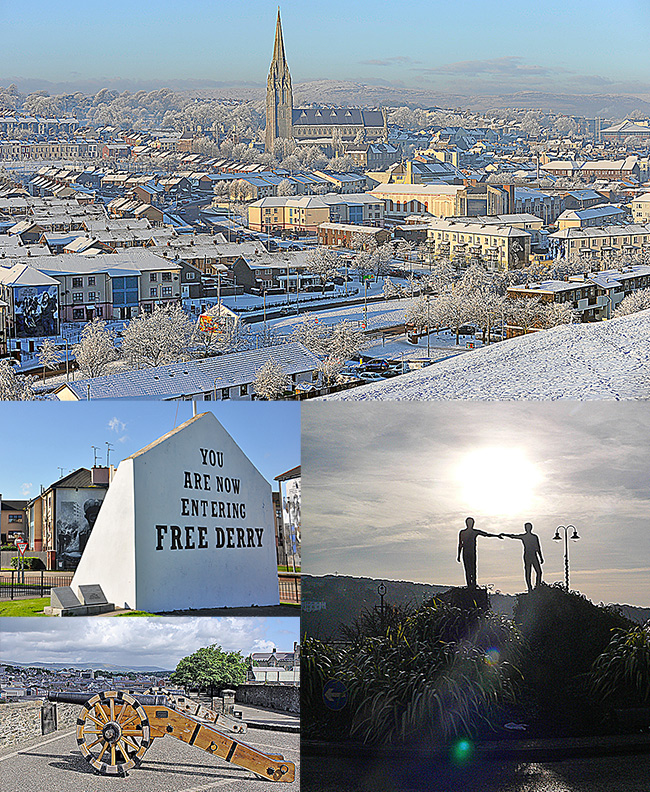

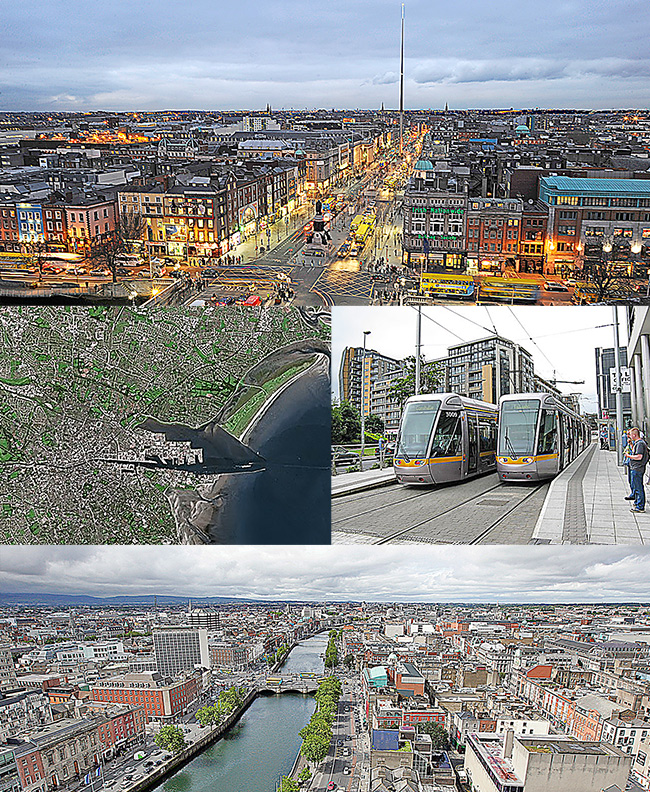

Dublin and Derry also want to be smart cities, but it remains to be seen whether the people with the expertise and knowledge to become smart citizens will be allowed to participate in the processes that will bring them to the level the EU requires.

Derry, being a smaller city, has a greater potential than Dublin to become an EU model for the perfect smart city. This is largely because it has a high number of green spaces, land that can be remediated and a topography suitable for energy recovery, flood defence, urban mobility and water retention. There are areas of the city that can be rebuilt and renewed as integrated infrastructures and systems, particularly with public transport.

• Liverpool and Dortmund are amazing cities – some might even say they are smart cities full of vibrant people . . . Dublin and Derry also want to be smart cities

Dublin, contrarily, would need to be rebuilt to meet all the EU’s requirements but the potential is not with concrete and steel, it is with the people who inhabit its cramped urban spaces.

Citizen emancipation and participation offer Dublin its best chance of becoming a partial smart and sustainable city but while sustainable food systems are practical projects, waste solutions will remain impractical until an integrated waste management system is adopted and realised. A functioning integrated public transport system will always be hampered by traffic issues and will only be resolved when non-essential traffic is removed and freight is carried into the heart of the city by smart transport.

Pilot projects that encourage the construction of energy-efficient buildings and paperweight waste systems for “maximum recycling and energy recovery” will only cover the cracks. Much more is needed.

Energy saving will reduce a city’s carbon footprint (a good thing) but it will not solve the more pressing ecological, environmental and social issues that every city faces today – not tomorrow.

Think of each city as that little flower about to be crushed by stupidity.

The irony is that the EU’s initiatives for smart cities and sustainable food security might be too late, and the responses by governments and institutions might be too pitiful to make a difference.

• Derry, being a smaller city, has a greater potential than Dublin to become an EU model for the perfect smart city

Critics of the EU’s research funding are quick to point out that research projects on their own will always remain works in progress and will carry no meaningful value until they are supported by private and public financing. The solution to the problem rests with the concepts of smart and sustainable.

A perfect smart and sustainable city will create wealth with its integrated systems because everything from energy to waste will be recovered, recycled and reused. Nothing will be lost, including labour and the economy will benefit because of the synergy created by closed systems. Unfortunately, these ideas need smart minds to make them work, and the will of the state to fund the ideas that result in the smart systems the EU is demanding. And no one doubts that this whole idea is a logistical conundrum for those tasked to make it work.

Max Horkheimer was a social philosopher who espoused the idea of collective emancipation rooted in education and knowledge. Born in Stuttgart, he argued that society will not function properly until emancipated individuals take responsibility for their home, work and social environments, and show ecological and social empathy.

“The fully developed individual is the consummation of a fully developed society. The emancipation of the individual is not an emancipation from society but the deliverance of society from atomisation.”

The social ecologist Murray Bookchin was very concerned about our cities and did not see much hope for the future of those who are required to live in them. Cities, he argued, “have changed from ethical arenas . . . into immense overbearing anonymous marketplaces”. They have lost, he wrote in From Urbanization to Cities: Toward A New Politics of Citizenship, “their form as distinctive cultural and physical entities, as humanely scaled and manageable political entities”.

“What we must clearly do in an era of commodification, rivalry, anomie and egoism is to consciously create a public sphere that will inculcate the values of humanism, cooperation, community and public service in the everyday practice of civic life.”

In modern Ireland there is no evidence that we are doing any of this, or even coming close to achieving a sensibility that nurtures these ideas in those who empathise with Horkheimer’s radicalised society or with Bookchin’s eco-society. “Capitalism’s grow or die imperative stands radically at odds with ecology’s imperative of interdependence and limit,” he argued, stating a fact that has no part in Irish economic thinking and political planning.

This is our little flower waiting to be crushed. Without an interdependent environment it will not survive. Now think of the city as that flower, and think of the irony. Think also about the EU’s position and its criteria for smart cities and smart citizens.

The talk from Brussels is all about citizen focus, knowledge sharing, integrated infrastructures and planning, sustainable food systems and sustainable urban mobility. The EU’s bureaucrats and politicians want indicators and metrics, models and standards, and they want demographic change.

• Citizen emancipation and participation offer Dublin its best chance of becoming a partial smart and sustainable city

On paper this sounds good. In reality it is a problem. These initiatives are research driven, with the emphasis on innovation and technology solutions. Scant attention is paid to eco-social solutions or to holistic thinking, planning and execution. The EU also wants environmental and social sciences solutions, but this is another problem. Because universities have specialised in business-driven innovation and technology, environmental and social sciences have been inadequately served by specialists with a genuine knowledge of eco-social sustainable practice.

Six universities across continental Europe are engaged in a masters programme for students interested in becoming sustainable food system specialists. It starts in September and so far is not attracting the students. This is only one indication that the expertise does not exist to implement the systems that all cities will need if they are to become smart and sustainable. Specialisation is the problem. There are very few people with practical knowledge who can take the holistic perspective that is required to solve today’s eco-social issues.

Despite six decades of warnings about climate change, food security and social imbalance, governments have been reluctant to address the issues that are now becoming very grave. By introducing smart city and sustainable food system programmes into their funding, the EU have taken an action that will benefit those cities with citizens who understand what must be done. For those who don’t understand, the future will be bleak. Like confidence, like irony, like a flower – here today, gone tomorrow.