26 April 2016

On this day 1916 – The Portobello Barracks murders

The murder and cover-up of three journalists by the British military in Dublin, 1916

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington pictured with her husband Francis, he was arrested and murdered in Portobello Barracks by the British military in 1916

AT 10am on Wednesday 26 April 1916, three men – all well-known journalists – were marched into the yard of Portobello Barracks in Dublin under the pretence of being questioned.

They were ordered by a British officer to walk to the end of the yard, as they turned to face him they were shot down by seven soldiers.

Two of the men – Thomas Dickson, editor of The Eye-Opener, and Patrick McIntyre, editor of The Searchlight – were killed instantly. Both men were well-known supporters of British rule in Ireland.

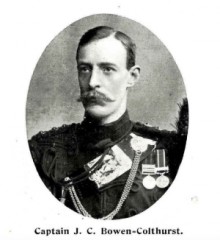

The third man was still moving on the ground. When this was noticed by Lieutenant Dobbin, the officer in command Captain JC Bowen Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles ordered four of the soldiers to fire another volley into him.

The shot man was Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a pacifist, suffragist, journalist and Irish nationalist.

The British troops wrapped the three bodies in sheets and buried them in the Barracks square.

The events that would lead to the murders in Portobello Barracks began on Easter Tuesday, when Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was walking home from a meeting he had organised in order to establish a citizen's civic guard aimed at preventing looting due to the break-down in law and order in the city.

Skeffington was a popular character in Dublin, a close friend of 1916 leader Thomas McDonagh, he had spent six months in prison for organising a campaign against recruitment to the British Army in the First World War.

A supporter Home Rule and editor of The Irish Citizen newspaper, he had initially backed the increasingly separatist elements of the Irish Volunteers but as a pacifist he distanced himself from the organisations as it became clear that a military confrontation with Britain was looming.

As 'Skeffy' crossed Portobello Bridge on Dublin's southside, he was arrested by the British military and taken to Portobello Barracks. Despite being opposed to armed actions of any kind much of the Establishment media – including the Irish Independent – frequently mis-labelled him as a “Sinn Féiner”.

A search of Francis revealed nothing but notes from the meeting he had attended. Despite this he was still held in the barracks. During this time he repeatedly requested his wife Hanna be informed of his whereabouts. This did not happen.

Later that night, British officer JC Bowen-Colthurst arrived and told the guards he was taking Skeffington to use as a human shield for a raiding party into Dublin city. It is claimed that Colthurst took a dislike to Skeffington after he noticed he was wearing a 'Votes for Women' badge, and declared him a “dangerous radical”.

Skeffington was first placed in a military vehicle and later left with Lieutenant Leslie Wilson who was ordered by Colthurst that he be shot dead if the 40-strong British Army unit was fired on during its raid further down the street.

As the military unit made its way down the Rathmines Road it encountered two teenagers, Laurence Byrne and James Coade who were on their way home from a sodality meeting in the local church. Colthurst told James Coade to take a cigarette out of his mouth and asked the teenagers did they not realise martial law was proclaimed?

The teenagers said they didn't know what 'martial law' meant and turned away to avoid trouble. Colthurst ordered one of his soldiers to strike the eldest of the pair, Coade, with his rifle. The boy fell to his knees from a blow to his head which broke his jaw, Colthurst then shot Coade dead as he tried to run away.

As the military patrol moved down the road, citizens began to flee in fear. Many took cover in nearby buildings.

The intended target of the raid was the home of Sinn Féin Councillor Thomas Kelly. However, the British Military unit had got its information wrong and instead it arrived at the tobacco shop of unionist Councillor James J Kelly.

Inside they found newspaper editors Thomas Dickson and Patrick McIntyre who had ducked in to escape the firing. Colthurst immediately arrested the pair, and two others on the premises, describing them as “very suspicious and dangerous characters”. He told them he had already shot people on the road and warned that under martial law he could “shoot them like dogs”.

When McIntyre explained he was the editor of The Searchlight, Colthurst dismissed it as “another rebel paper”. McIntyre was at pains to point out it was a “loyal paper”.

The soldiers then wrecked James Kelly's shop and as they were leaving tossed in hand grenades, destroying it. Colthurst justified this in his report claiming the shop was “infested with Sinn Féiners”.

Colthurst is also accused of shooting another civilian, Patrick Nolan, who was severely injured at Delahunt's grocery shop but survived due to swift medical intervention.

The three journalists were brought back to Portobello barracks and murdered the following morning.

While the British military repeatedly attempted to blame the murders on a deranged Colthurst, testimony from other British soldiers confirms that the Engineering Officer at the base brought in a mason and a labourer to repair the wall against which the three journalists were shot – removing the bullet-riddled bricks – in a deliberate attempt to cover-up the killings.

After the murders, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and her sister, Mrs TM Kettle, arrived at Portobello Barracks to ask about Francis. Hanna and her sister were then arrested “on suspicion of being Sinn Féiners” before Colthurst spoke to them in the guardroom and told them he knew nothing of Mr Skeffington and to leave immediately.

Colthurst then led a raiding party to the home of the Sheehy-Skeffingtons in a futile attempt to find incriminating evidence that could be used to justify his extrajudicial murder of Francis. During the raid they fired through the windows while Hanna, her seven year-old son and a maid were inside.

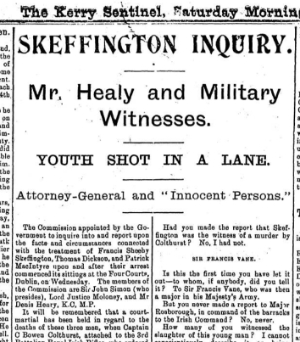

The killings caused outrage amongst Dubliners. One British Army officer, Major Francis Fletcher Vane repeatedly contacted senior British military leaders demanding Colthurst's arrest. Vane was persona-non-grata with some in the British military after numerous complaints were made against him for an incident in March 1915 during which the Anglo-Irish officer declared himself an Irish nationalist while acting as a recruitment officer for the British Army in Ireland.

Speaking to Major James Rosborough in the aftermath of the killings, Vane said:

“Think of the effect these murders will have on the reputation of the Army. Worse still, think of the effect they will have on America and the colonies where there are large amounts of Irish people.”

Rosborough, however, leapt to the defence of Colthurst – explaining that the murders were carried out for “fears that the prisoners might be rescued or escape”.

On 8 May the body of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was given back to his father on condition that the funeral be held early in the morning and his wife Hanna not be notified. In return, British General Maxwell promised that Colthurst would be tried and punished. He was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

His widow, Hanna, campaigned for an inquiry into her husband's murder. Speaking in the USA, she said of Francis:

“My husband was an antimilitarist, a fighting pacifist, a man gentle and kindly even to his bitterest opponents, who always ranged himself on the side of the weak against the strong whether the struggle was one of class, sex or race domination. Together with his strong fighting spirit he had a marvelous, an inextinguishable good humour, a keen joy of life, a great faith in humanity and a hope in the progress towards good.”

Colthurst was eventually arrested and court-martialed and declared insane.

Vane was swiftly dishonorably discharged from the British military on 30 June.

Writing to Irish Parliamentary Party MP for Dublin, John Dillon, during the Inquiry in October, he said:

“[I] exposed villainy in high places and was dismissed. I was in fact dismissed because I saved some innocent Irish lives.”

In 1917, an attempt by Vane to publish a book on his experiences during the Easter Rising and the Portobello murders was thwarted by the British military censors – the proof copies were seized and the original manuscript destroyed.

As for Colthurst, after spending a year in a Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum he was declared recovered and moved to Canada on a full British military pension, settling in what is now the Sooke Harbour House Hotel.

Colthurst apparently feared retaliation for his role in 1916. He first moved to Terrace before settling on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, partially due to its remoteness, strong Protestant character and popularity amongst other imperialists. He spent his time in Canada writing to the British Colonist newspapers on various issues and sponsoring evangelical Anglican events.

In March 1934 he spoke at a conference entitled “The British Empire: Past, Present and Future” during which, apparently without irony, the murderer of three newspaper editors and a child returning from Church, he told the audience: “The two glories of the British Empire are bibles and newspapers”.

Colthurst died of coronary thrombosis in his bed in Penticton, British Columbia on 11 December 1965.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures