1 February 2016 Edition

The shame of Easter Week? Unionist responses to the 1916 Rising

• Edward Carson and James Craig

Unionists from Ulster played a direct role in the hostilities of Easter Week

ONE of the lesser-known aspects of the 1916 Rising is the unionist response to it in Ulster. Broader unionist reaction may require little by way of imagination; nevertheless, in preparation for a lecture in March at Féile an Earraigh I have been investigating the individual reaction of various unionist figures in 1916. Here is a flavour of some of the findings.

Unionists from Ulster played a direct role in the hostilities of Easter Week. Reserve units of the 36th (Ulster) Division were sent from Belfast to Dublin to help quell the disorder. Such units contained many men from the Ulster Volunteer Force, a theme echoed in John Dillon’s speech to the House of Commons when he read a statement by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington in which she referred to the ‘Belfast accents’ of the British troops raiding her home in Dublin. Moreover, units of the Loyal Dublin Volunteers were among the first to engage the rebels on Easter Monday (Quincey Dougan, The Loyal Dublin Volunteers).

As well as personnel, UVF equipment also played a role. In his Bureau of Military History witness statement, Belfast republican Denis McCullough described how UVF equipment, such as bandoliers, was purchased in anticipation of a Rising. Furthermore, UVF weapons were procured by the British Army in instances where arms and equipment had been lacking, before later being “handed back in good condition and beautifully clean”.

• The Loyal Dublin Volunteers were among the first to engage the rebels on Easter Monday

Initial reaction appears to have been trivial and pragmatic in nature.

One such letter received by Edward Carson suggested that the UVF had been mobilised in Belfast, allowing for soldiers to be redeployed to Dublin; the letter writer observed that, as a consequence, the police kept a low profile and the pubs did not see fit to close. Robert H.H. Baird, proprietor of the Belfast Evening Telegraph, on the other hand, found himself inconvenienced in Dublin by the whole affair and was more concerned with the fate of his luggage and the impact on sales for his newspaper.

Once the dust had settled and the magnitude of the event had been realized, it is possible to identify some of the more calculated reaction.

A dominant theme in the papers of Edward Carson and Wilfrid Spender appears to be a fear that the Government would demand the surrender of all weaponry held by volunteer groups in Ireland. Unionists felt that it would be unfair to punish the Ulster Volunteers for the actions of ‘Sinn Féiners’ in Dublin. Belfast’s Unionist Lord Mayor, Crawford McCullagh, was in correspondence with Prime Minister Asquith on this matter and he argued that the presence of arms and the peaceable state of Ulster were inseparable. Indeed, Carson was under immense pressure from both sides of this debate before Asquith eventually moved to dispel the entire saga as a rumour.

Surprisingly, Carson appears to have been assigned a portion of the blame for the Rebellion. From early May 1916 he is in receipt of threatening mail for having “given a lead” in the matter of rebellion by raising the Ulster Volunteers. One man even forced his way into Carson’s home in London with the intent of doing him physical harm, thus prompting Lady Lilian Spender to write on 13 May 1916 that “I’ve no doubt there are plenty who would like to murder him.”

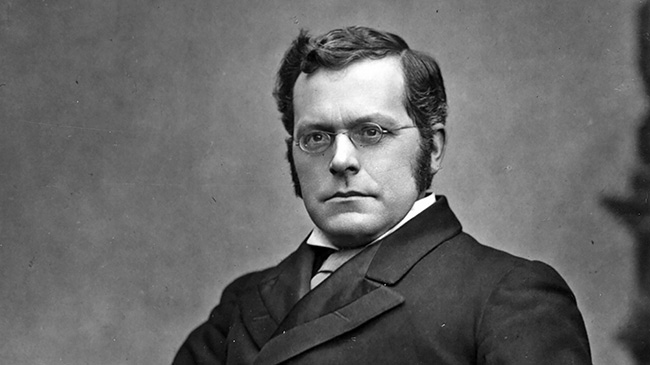

• Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell

In terms of blame, a good deal of it appears to have been attributed to Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell, who eventually resigned in May 1916. The accusation from unionists was that Birrell had failed to act on intelligence which warned him of a potential rebellion. This seems to be supported by the findings of the Royal Commission.

Among the more predictable responses were those of treachery. For unionists the Rising proved that Irish nationalists were, at heart, disloyal and could not be trusted with the claims of ‘loyalty’ to the Empire made by John Redmond. Indeed when placed in the context of ‘The Great War’ it was an act of treason. There was also a firm belief that the Rising would pass into the annals of insignificance along with similar rebellious failings of the past. Lord Selborne, for example, described it as “the usual Irish tragic comic opera”, while the old Liberal Unionist Adam Duffin likened it to a “comic opera founded on the Wolfe Tone fiasco a hundred years ago”.

A recurring theme in many unionist accounts suggests that vengeance was not eagerly sought. Unionists applauded the imposition of martial law and were determined that justice should be achieved, however when the trials of the rebel leaders began, Edward Carson urged caution: “It will be a matter requiring the greatest of wisdom . . . dealing with these men. Whatever is done, let it be done not in a moment of temporary excitement but with due deliberation in regard to the past and to the future.”

JASON BURKE is Co-ordinator, East Belfast & The Great War Research Project