5 January 2016 Edition

Goals win more than games

BETWEEN THE POSTS

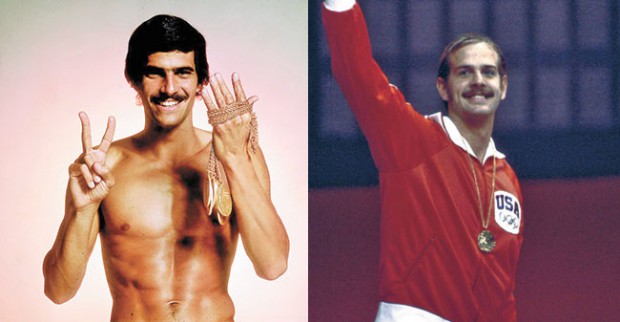

• Mark Spitz and John Naber

The moment you begin to monitor and match time with effort is the moment you begin to adapt basic goal-setting

CONFORMITY is a powerful social force. Come January each year, we’re exhorted to make public promises of changes we intend to keep. Media, advertising and even friends or family may all play a part in the annual exhibition of empty gestures known as New Year’s resolutions. Invisibly, imperceptibly, each of us is expected to conform with this tradition. A tradition which apparently goes as far back as the Roman Empire

Yet traditions aren’t always rational. Conformity doesn’t make resolutions sustainable.

Last December, two-thirds of us planned a fresh start. The most popular New Year’s resolutions were losing weight, better diet, increased fitness and improved work-life balance. According to a YouGov survey last December, one third of those who make a resolution will have broken it by the end of January. Only one in ten people said that they never break their New Year’s resolution. By those maths, the traditional pledge to change has a 90% failure rate.

Around the country, many individual athletes and players, coaches and teams will be engaged in their own preview of 2016. In international sport, there will be the European Cup finals and the Olympics. Ireland, North and South, will be well represented at both events. International rugby will provide a platform for Ireland to recover its form after falling short in the World Cup. Back home, club and county competitions in Gaelic games will be as hotly contested as ever. If we were to witness a 90% failure rate in forthcoming sporting competitions, would anyone celebrate? What would happen to sport if one third of players or athletes gave up their training programmes by the end of January?

Those involved in sport know resolutions in the traditional sense make no sense. They talk about goal-setting, a technique which is used in high-performance sporting environments. Goal-setting is also applied in other organisational contexts. In the sporting arena, goal-setting began to gain traction in the 1970s.

One of the most famous examples of the application of goal-setting in sport is the case of John Naber. After watching American swimmer Mark Spitz clean up with seven gold medals at the 1972 Olympics, John Naber began to dream of winning a gold medal himself one day. Of course, it helped that Naber himself was already an accomplished swimmer. But he realised that to fulfil his dream, he would have to improve his own personal best by four seconds.

“It’s a substantial chunk,” said Naber, “but because it’s a goal, now I can decisively figure out how I can attack that. I have four years to do it in. I’m watching TV in 1972. I’ve got four years to train. So, it’s only one second a year. That’s a substantial jump.”

Naber, however, broke it down into how much he would need to improve per month (about one tenth of a second).Then he worked out how much he would need to improve each day and each session. At the Montréal Olympics in 1976, John Naber won his gold medal in the 100m backstroke. Naber is still widely cited in goal-setting research.

Goal-setting is now understood to be an essential part of behaviour change. Various theories help to explain the psychology of this. Common to all of these is the benefit that goal-setting has for motivation. This motivation, together with the capability and the opportunity, is what makes goal-setting an effective instrument for change and success. But it’s not without challenges also. Think about the willpower and stamina required to pursue a dream over four years, edging further towards it one exacting training session at a time. Imagine all the changes that can happen in your life and around you in four years. Yet that’s what people in sporting events such as the Olympics commit to do. All of which serves to underline the importance of setting the right goals. Added to this is the method by which improvement is monitored.

Recently, I read an article about the value of taking time on a Sunday to write a note or letter to myself about the week ahead. It’s a method of self-monitoring: self-reflection with a very practical slant. Looking ahead to what I must do and my plans in the next few days, and considering whether my attention and time matches what is most important in life. The moment you begin to monitor and match time with effort is the moment you begin to adapt basic goal-setting.

As one of the greatest sportspeople of all time, Muhammad Ali, once said: “What keeps me going is goals.” The trick is to find your own.