1 December 2015 Edition

H-Blocks/Armagh torture – under international scrutiny

• The treatment of republican POWs was systematic, sustained and politically-motivated as it aimed to break the prisoners' will to resist

‘The intensity of the oral hearings was such that a number of former prisoners were on the verge of a breakdown as they relived their experiences’ – Séanna Walsh, former O/C, republican POWs, Long Kesh

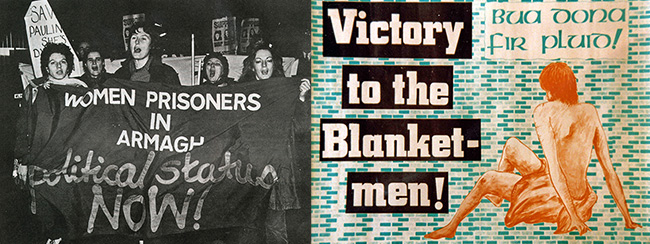

THE SYSTEMATIC ABUSE of republican prisoners in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and Armagh women’s prison between 1976 and 1981 is the subject of an international tribunal being driven by prisoners’ advocacy group Coiste na n-Iarchimí.

In a series of local tribunals held in venues across the North, solicitors from Belfast-based human rights law firm Ó Muirigh Solicitors took statements from former protesting prisoners.

In their endeavour to get as wide a geographical spread as possible, testimonies were collected from 75 Blanket and No Wash protesters in Belfast, Derry City, Gulladuff in south Derry, and in the Newry/south Armagh area.

Up to 10 women who were imprisoned in Armagh women’s jail also made statements, describing their treatment by the prison authorities as they protested for the right to be treated as political prisoners.

These statements would form a central part of the hearings for the panel of jurors headed by former Canadian Solicitor General Warren Allmand.

Sitting with Allmand (also a former Member of Parliament and Cabinet minister in Canada) were Richard Harvey QC (who represented the family of one of the Bloody Sunday dead, James Wray) and Doctor John Burton (who practised family medicine in south Derry for 23 years). Burton has, since 2004, been involved in issues relating to human rights and civil rights in the North.

During their hearings, the panel heard oral testimonies from 34 republican Blanket protesters. Evidence from two loyalist Blanket protesters was also presented to the tribunal.

A practising psychiatrist with many years of experience in dealing with people suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and trauma gave evidence. Two former Long Kesh prison governors also appeared and addressed the jurors.

• Séanna Walsh, Dr John Burton, Warren Allmand and Pádraig Ó Muirigh

The pair, who have been dealing with Coiste through its Legacy Programme, agreed to give their evidence anonymously and their testimonies confirmed (if it needed to be confirmed) that the prison system in the North was heavily politicised by the British Government.

Another whose evidence was highly significant was criminologist Phil Scraton.

Scraton is currently Professor of Criminology in the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice, School of Law, at Queen’s University, Belfast. He’s also Director of the Childhood, Transition and Social Justice Initiative. His research includes the investigation of and inquiry into controversial deaths, particularly deaths in custody; the marginalisation and criminalisation of children and young people; the politics of imprisonment; analysis of disasters and their impact on the bereaved and survivors. His testimony focused on the British Government’s tactics relating to prison protests.

Séanna Walsh, Coiste’s legacy worker who is central to the project, spoke to An Phoblacht and explained the significance of the tribunal and what Coiste intends to do with the findings.

He’s keen to point out that, with the volume of information, evidence and testimony involved, it is “more than likely the findings will not be complete until Easter 2016”.

Walsh says the final report will obviously be launched in Belfast and Dublin but he hopes it will also be launched in Brussels and London.

“We would like to bring it to New York as well because we are determined to use the findings of the tribunal to break through the blanket of disinformation that the British threw over the treatment of prisoners in the prisons during the protest years and which still holds sway to this day.

“What we are seeing – and this is being reinforced with the breakthrough achieved when the ‘Hooded Men’ succeeded in bringing their case back to the European Court – is that the ill-treatment of those imprisoned and on protest was systematic.”

• • •

Sitting in Coiste na n-Iarcmimí’s Belfast office, Séanna Walsh explains that the treatment of the protesting prisoners in Long Kesh, Armagh women’s prison and in Crumlin Road Jail “was unique in that it was protracted, systematic and sanctioned from the top of the British Government”.

He acknowledges that certainly there have been plenty of instances throughout the history of the conflict when the prison authorities have brutalised republican POWs.

“There is plenty of evidence of this in the 26 Counties, in England, and even in the North itself. Even when prisoners had status they were brutalised, most notably when Long Kesh was burned in 1974.”

• The brutal treatment of prisoners caused public outrage, North and South

The politics of the prison struggle between 1976 and 1981 meant that the treatment of the protesting prisoners was systematic, sustained and politically motivated as it was being used to break the protesters’ will to resist, Séanna says.

“The politics of the situation were summed up by one of the governors who gave evidence to our inquiry. His contention was that by withdrawing political status the British Government brought conflict into the prisons.”

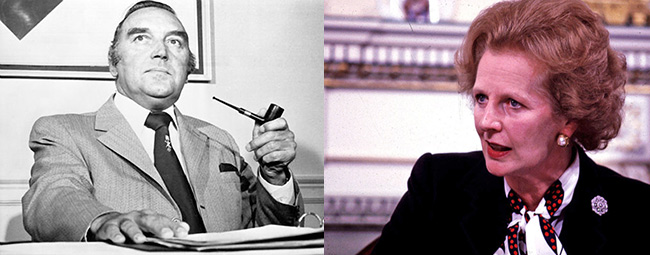

The governor maintained that this was a deliberate act on the part of the then Labour Government as they rolled out the criminalisation policy as they tried to shift the ground on which the struggle was being fought from a ‘guerrilla war’ to a criminal conspiracy.

“And in a practical shift of emphasis,” explains Walsh, “the prison warders joined the ranks of the RUC and the British Army as they joined the fight to crush republican resistance.

“Looking back on what was happening,” says Walsh as he lists the methods deployed to break the prisoners, “you had physical assaults when they used batons and boots, they drenched people with hoses, doused prisoners with highly toxic disinfectant, and they used the food as a weapon too.

“Then they deployed the table search, which was refined into the mirror search, which amounted to sexual assault.

“And all this was being inflicted on prisoners who were locked up 24 hours a day with no physical or mental stimulation as they were denied exercise and refused books or newspapers.

“This was all with the objective of breaking the Blanket men and the women in Armagh, breaking them psychologically by whatever means necessary and what underpinned it was how the system set out to demonise and dehumanise naked prisoners.

“The British Government, through the NIO and down to the prison authorities, operated a ‘light touch’ discipline and control policy and gave the Screws free rein to do what they wanted and this led to casual and gratuitous violence.”

• • •

Documents uncovered by solicitors and researchers working for Ó Muirigh Solicitors support the claims that the violence meted out to the protesting prisoners in the H-Blocks and in Armagh was sanctioned at the highest level.

In one document from 1975 titled Contingency Plan to Accommodate Changes in Prison Population it is clear that the British Government and the NIO were intent on confrontation and were planning for it.

The document says:

“It is expected that the newly-convicted ‘non special category’ prisoners [those denied political status] housed in the H-Blocks will be a source of trouble. It is expected that they will refuse to work, refuse to wear prison clothing and refuse to associate with others of their own persuasion.

“These problems will have to be solved by the prison staff by resolute adherence to the standing orders and agreed policies.”

• Labour Government's Roy Mason and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

As the protest grew in 1977, an NIO document from a Mr Concannon advocates a tougher stance as “softening up” wasn’t an option as that would “show concern”.

In 1979, after almost a year of the ‘No Wash’ protest, the notorious ‘mirror search’ was introduced.

It replaced the ‘table search’, when prisoners would be tipped up like a wheel barrow on a table and a Screw would carry out an anal search.

The mirror search was carried when the naked prisoner was forced to straddle a mirror set in foam. A Screw, on either side of the prisoner, would twist his arms to force him to bend while a screw behind would kick him behind the knees. causing him to collapse over the mirror.

This exposed the prisoner’s anus and allowed the ‘searcher’ to carry out a finger search, on occasion inserting his finger into the prisoner’s anus.

At least one prisoner recounted that after going through the anal search the prison offcer who carried out the search then forced his fingers into the prisoner’s mouth.

• • •

Ó Muirigh Solicitors have found documents which demonstrate that the NIO was concerned to censure or pressure anyone who might expose what was happening.

Two members of the Board of Visitors (a supposedly independent oversight body) who showed sympathy towards the protesting prisoners in Long Kesh were written to as their comments “had an adverse effect on morale” of the prison warders. This was brought to the attention of British Secretary of State Roy Mason. Both men were “written to”. Having drawn the attention of a bullying Cabinet minister and the state’s security apparatus, both retreated, saying their comments were “misunderstood”.

• Former protesting prisoners gave statements on the situation in the prisons to a series of local tribunals held across the North. The findings will be launched in Belfast, Dublin and further afield

The case of outspoken Armagh chaplain and human rights campaigner Fr Raymond Murray is even more blatant. In October 1978, two NIO officials discussed approaching the Catholic Church Hierarchy and asking them if Fr Murray “is the most suitable priest” for the job.

As with the cases of ‘The Hooded Men’ torture victims, Britain was able to sideline those who argued that their treatment was torture but, with dogged perseverance, the men subjected to that brutal regime forced the European Court of Human Rights re-examine its findings.

It’s hoped that the independent tribunal examining the prison protests of 1976 to 1981 will expose the regime that operated in those years as being a one built on a ruthlessly-implemented system of violence, brutality, humiliation and degradation of prisoners – torture.