1 July 2015 Edition

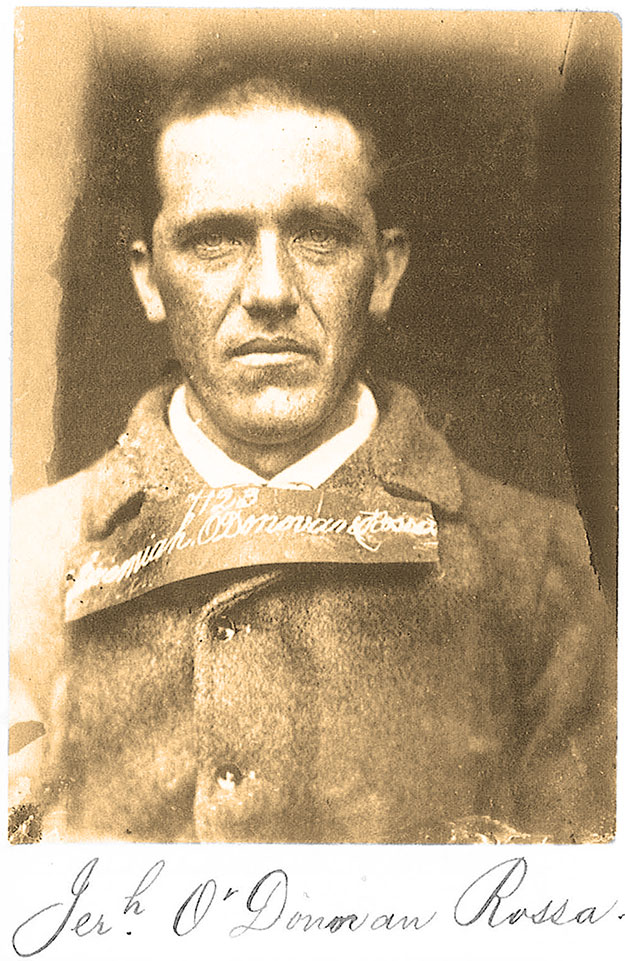

O’Donovan Rossa – Unrepentant Fenian bomber

Commenting on the bombings in England, Rossa noted they were ‘to show England that she had better give Ireland her own parliament. England is at war with Ireland, and Ireland should be at war with England’

IN 1856, O’Donovan Rossa began a revolutionary career that would span over 50 years when he became a founding member of the Phoenix Society in west Cork. Those who had joined the society were frightened by the state of Ireland in the aftermath of the Famine and the disastrous failure of the 1848 rebellion.

Parallel to the rise of the Phoenix Society in 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) had been established in Dublin by James Stephens and a coterie of supporters. Stephens, who was on an organisation tour of Ireland, met with Rossa in Skibbereen and recruited him into the IRB.

Merging the two organisations, Rossa became an enthusiastic conspirator and an active recruiter for the IRB. In October 1858, he had attended moonlight drilling at Skibbereen organised by an Irish-American officer, P. J. Dowling. Here he trained with pikes, guns and rifles in preparation for a future rebellion.

In May 1863, Rossa left for New York City, where he worked alongside John O’Mahony building the Fenian Brotherhood and witnessed first-hand the New York Draft Riots in addition to the spectacle of the Union Soldiers parading and drilling as America erupted into the Civil War. While in America he had received an offer to return home and act as the business manager for The Irish People, a propaganda newspaper.

He returned to Ireland and moved permanently to Dublin to become business manager. He also wrote articles under the pseudonym “Anthony the Jobbler” and produced poetry such as his famous The Soldier of Fortune.

An informer on the staff of The Irish People, Pierce Nagle., had discovered amongst papers in the Irish People offices a letter signed by James Stephens promising that 1865 would be the year of action and that “the flag of Ireland – of the Irish Republic – must this year be raised”. With this information, on the evening of Friday 18 September 1865, Dublin Castle authorised the suppression of The Irish People and arrested its leading figures, including O’Donovan Rossa.

Taken to Richmond Bridewell, where he was held on remand, Rossa was eventually tried in December 1865 for conspiracy before the erstwhile nationalist William Keogh. Declaring his trial to be a ‘legal farce’, he had decided to make his trial, as one contemporary noted, “a defiance of the British Government, a merciless exposure of its utterly unfair methods in conducting political trials and of the rottenness of his judicial system in Ireland”. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Between 1865-71, Rossa was held in several British prisons, including Chatham, Portland and Milbank. His treatment by prison staff, in addition to working alongside common criminals, increasingly irked O’Donovan Rossa, however. While at Milbank, his comrade Edward Duffy had taken ill and despite continued appeals he was not allowed to visit Duffy. Learning of his death from other prisoners through gratings, he was spurred to write his most famous poem, Duffy is Dead. Lamenting his old friend, it gave a great sense of the pain O’Donovan Rossa was experiencing whilst in prison as he wrote:

“Duffy is dead!” a noble soul has slipped the tyrants chains,

And whatever wounds they gave him, their lying books will show,

How they very kindly treated him, more like a friend than foe!

In February 1868, Rossa was transferred to Chatham Prison, where again he regularly suffered bread and water punishments. Placed working alongside common criminals he refused to work within the prison. Taken before the jail governor for ‘idleness’, he refused to salute him, incurring a punishment of three days on bread and water. By 15 June 1868, he declined to meet the governor and was forcibly taken to the his office, where Rossa refused to sit down and again salute. The following day he determined vengeance and when the governor visited his prison cell, on his rounds, Rossa threw the contents of his chamber pot over him shouting: “That . . . is the salute I owe you!”

For this he was sentenced to 34 days with his hands cuffed behind his back, followed by a further 28 days of bread and water punishment. Having completed his 28 days of bread and water punishment. He was then placed on six months of a ‘penal class’ diet but shortly afterwards he again returned to bread and water punishment for a refusal to pick oakum (used in building wooden ships). Taken to solitary confinement, the prison authorities withdrew his bed and took his clothing, forcing him to sleep naked on the floor.

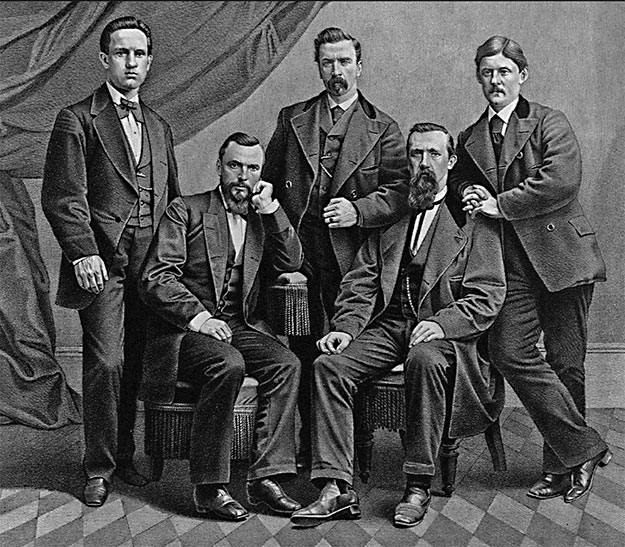

Resultant from an inquiry into the treatment of Fenian prisoners by the Earl Devon, O’Donovan Rossa was offered a conditional amnesty in 1871. The terms of the amnesty were that convicted Fenians could not return to Britain for the duration of their sentence. As he was sentenced to life imprisonment this meant he could not return to Ireland for 20 years. Choosing to accept the conditional amnesty, Rossa was released from prison on 7 January 1871. With John Devoy, Charles Underwood O’Connell, John McClure and Harry S. Mulleda, he sailed for New York aboard the trans-Atlantic steamer Cuba. Becoming known as ‘The Cuba Five’, they arrived in America where differing political factions sought to control them. Remaining aloof from American politics, the Cuba Five, later joined by further exiles, established an Irish confederation to unite Irish-America.

• ‘The Cuba Five’ – John Devoy, Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, Charles Underwood O'Connell, Henry Mulleda and John McClure

Despite early success, the confederation became another faction within a bitterly divided Irish-America. Having failed with the confederation, however, they turned their attention to Clan na Gael, a secretive organisation committed to rebellion in Ireland. Through the Clan, Rossa became associated with Patrick Ford, the proprietor of The Irish World newspaper, and wrote a column for Ford. By 1876, the newspaper had advocated a Skirmishing Fund to raise money for bombings in Britain. Taking charge of the fund, Rossa regularly called through Ford’s newspaper for direct action in British cities and successfully raised $5,000 to do so.

Attracting the attention of Clan na Gael, he was forced to share the fund with a board of trustees led by John Devoy. The trustees, however, believed that Rossa should not be in charge of the fund because he was not working within a secretive manner.

Under immense pressure and tension, with relations between the trustees increasingly untenable, combined with the death of two of his children, Rossa took to excessive alcohol abuse, with Devoy receiving reports of Rossa staggering in and out of saloons.

Devoy had also discovered that Rossa, in a state of drunkenness, had misappropriated funds from the national collection, his wife noting that in his present state he was a danger to the fund. Sent to a convent in Chatham to recover, when he emerged he broke with Clan na Gael and established a new organisation called the ‘United Irishmen of America’.

Meeting at Philadelphia on 28 June 1880, the United Irishmen of America resolved to adopt a dynamite campaign in Britain. The agents of this dynamiting campaign were referred to as ‘The Skirmishers’ and they undertook a series of small-scale bombings in British cities between 1881-83.

The first of these bombings took place at Salford Barracks, Manchester, on the evening of 14 January 1881, killing a seven-year-old boy. A further series of explosions occurred at Liverpool, Glasgow (where the city was plunged into darkness) in addition to two significant bombings in London’s Whitehall in March 1883 (where the Skirmishers destroyed the Offices of the Local Government Board, which they wrongly believed to be the Home Office) and the headquarters of the London Times newspaper.

• Damage to Scotland Yard police headquarters in London after it was blasted in a Fenian bomb attack

From New York, Rossa acted as the spokesman for the dynamitards. Commending on the March 1883 bombings, Rossa noted they “were intended to do all the damage possible, and it was done to show England that she had better give Ireland her own Parliament. England is at war with Ireland, and Ireland should be at war with England”.

To establish a semblance of professionalism to the dynamite campaign, Rossa set up a dynamite school at Brooklyn for the training of Irishmen in the handling and use of explosives.

Celebrating the school, Rossa held that “young men have come over from England, Ireland and Scotland for instruction and several of them have returned sufficiently instructed in the manufacture of the most powerful explosives”. One of those who had returned to Britain was Timothy Featherstone, who was the heading of a skirmishing cell in Cork and worked closely with two other graduates named Henry Dalton and John Francis Kearney, who commanded a cell in Glasgow. The three cells were later discovered by a British agent-provocateur named ‘Red’ Jim McDermott who, having worked his way into the conspiracy using a letter of introduction he had secured from Rossa, dismantled the conspiracy and destroying O’Donovan Rossa’s organisational network in Britain.

In the autumn of 1883, Clan na Gael adopted a more professional and resourced dynamiting campaign. Representative of this their dynamitards successfully detonated explosives on the London underground railway, Pall Mall, Victoria rail station and destroyed the headquarters of Scotland Yard in addition to detonating a bomb in the chamber of the House of Commons.

While Rossa was not involved with these bombings he regularly claimed responsibility and was greatly associated in the public psyche with explosions in Britain. It therefore came as no surprise that he was the subject of an assassination attempt by an Englishwoman named Yseult Dudley who shot him repeatedly at Broadway on 2 February 1885. When asked why she tried to assassinate Rossa, she told the police: “I have shot O’Donovan Rossa. I am an Englishwoman and I shot him because he was O’Donovan Rossa. You know the rest.”

On 19 May 1894, O’Donovan Rossa left New York to return to Ireland for the first time since his trial in 1865. Arriving in Cobh Harbour, he was met by a by a huge crowd that had assembled in anticipation of his arrival. His arrival had been stage-managed by the IRB and amongst the crowd were armed men for his protection in case an attempt was made to arrest him.

Beginning a lecture tour of Ireland, he travelled throughout the country, talking about his experiences in prison and unveiling a monument to the Manchester Martyrs in Birr, County Offaly, on 22 July.

• Mary Jane O'Donovan Rossa

Returning to Ireland in 1905, with his wife, Mary Jane, he had intended to settle in Cork. However, with Mary Jane’s health declining, he was forced to return to New York. While his wife’s health improved, Rossa increasingly displayed a marked deterioration and was plagued with muscular spasm and degeneration. Diagnosed with chronic neuritis, Rossa was increasingly confined to bed, and with declining years displayed signs of dementia as he increasingly became impaired and considered himself to be back in prison.

Moved to St Vincent’s Hospital, Staten Island, he was confined to a wheelchair, being wheeled around the halls and wards where he spoke nothing but Irish and regressed into his childhood.

Dying on 29 June 1915, his wife, Mary Jane, recalled:

“There was no struggle. There was pain. He simply stopped breathing and lay perfectly still with a large, conscious solemn gaze as if he saw grand visions of the future that satisfied his heart and soul.”

Dr Shane Kenna is the author of War In The Shadows: The Irish-American Fenians Who Bombed Victorian Britain and Conspirators: A Photographic History of Ireland’s Revolutionary Underground – see review

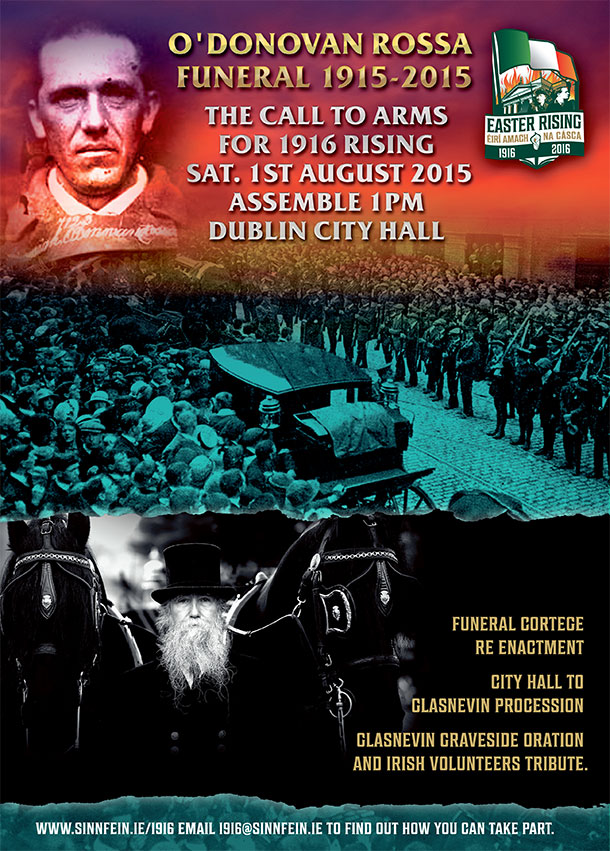

Public urged to get involved in centenary commemoration

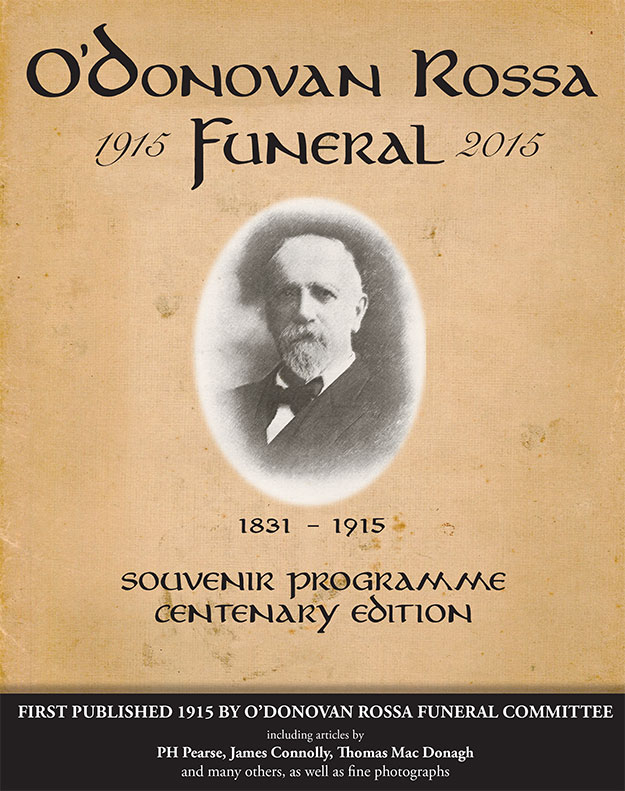

O’Donovan Rossa Funeral Souvenir Programme Centenary Edition

First published 1915 by O’Donovan Rossa Funeral Committee

This is a Centenary edition, fully reproducing the original brochure published after the funeral in 1915, including articles by Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas Mac Donagh and many others, as well as fine photographs.