4 May 2015 Edition

Boxty is back (and other traditional food revivals)

Ireland sits last on the traditional food table of Europe

MICHAEL 'MITEY MAC' McNally, toggle-haired and thin-boned, stares out at the ocean, remembering. “We were never educated to stay here and love the place and the produce.”

Once a fisherman, he knows what is beyond the Skelligs – vast emptiness where the sea and the sky cannot agree where to meet. From his small farm at the western edge of the Beara peninsula, the salt-sea air chaps his lips.

Today is a typical Beara day. The sun is high in a watery blue sky. The sea throws its salty spray onto the sparse land. Rain is in the air and, sure enough, it sweeps down from the mountain. The sky darkens. Within half an hour, a dirty grey blanket alters the illumination of the land. The light fades almost to twilight.

It is time to make lunch.

Pan-fried fresh mackerel and whole boiled potatoes – the old favourite.

Mackerel are capricious. Fishers have always known this. From Dinish to Cape Clear and around to Garinish, mackerel have defined the lives of coastal communities for countless centuries.

Stephen Crane, an American writer who visited Cape Clear in the last years of the 19th century, described the life:

“The mackerel, beautiful as fire-etched salvers, were passed to a long table. Each woman could clean a fish with two motions of the knife. Then the washers, men who stood over the troughs filled with running water from the brook, soused the fish.

“The fish were carried to a group of girls with knives, who made the cuts that enabled each fish to flatten out in the manner known of the breakfast table.

“After the girls came the men and boys, who rubbed each fish thoroughly with great handfuls of coarse salt, whiter than snow, which shone in the daylight, diamond-like.

“Last came the packers, drilled in the art of getting neither too few nor too many mackerel into a barrel, sprinkling constantly prodigal layers of brilliant salt.”

In the early 1930s, the mackerel disappeared completely. When they returned, the knowledge that had been passed down led the fishers to the fish.

“The old fishermen always knew the best geographical points to go to to get the mackerel," says Mitey. “If they weren't there you'd see the fowls in the water and you'd chase over towards them.”

The fishers used fixed nets anchored to stalls on the seabed at specific points up to 30 feet deep. When the mackerel moved they ran straight into these nets, the force of the fish lifting the nets out of the water.

“It was a great sight in the morning at dawn when the fish would start to move,” says Mitey. “We caught the fish with netting with a three-inch mesh – which ensured all the small mackerel went through it so we caught only the prime fish, the big, fine, fat mackerel.”

An increasing demand for mackerel was soon met by people who wanted to make big money. Unlike the Garinish fishers, whose livelihoods depended on the mackerel, entrepreneurs launched large factory ships and sent them in search of the mackerel in the open sea. “Two of these super trawlers would catch in one night what would keep a community as large as this whole parish going for the year,” says Mitey.

The market for mackerel collapsed in the early 1980s. Now the mackerel are back again and the fishers are using old methods to sustain the stocks. On Dinish island, they fast-freeze whole mackerel and sell them where they can.

Paul Farrelly of Killeshandra was 19 when he got laid off from the building sites. It was the boat for England or boxty for Ireland. He decided to stay and now, three decades later, he has a thriving business making and selling boxty to shops in Cavan, Leitrim and Longford, and via Musgraves of Cork to various Centra and SuperValu outlets around the country.

He says it was one of those little accidents of life. Accident or not, to make a success of an artisan food business in the early 1980s required more than providence.

His mother, Nan, who ran a home bakery, provided the expertise and skill, and away they went, grating and squeezing floury Kerrs Pinks to make a boiled boxty rooted in the tradition of west Cavan life.

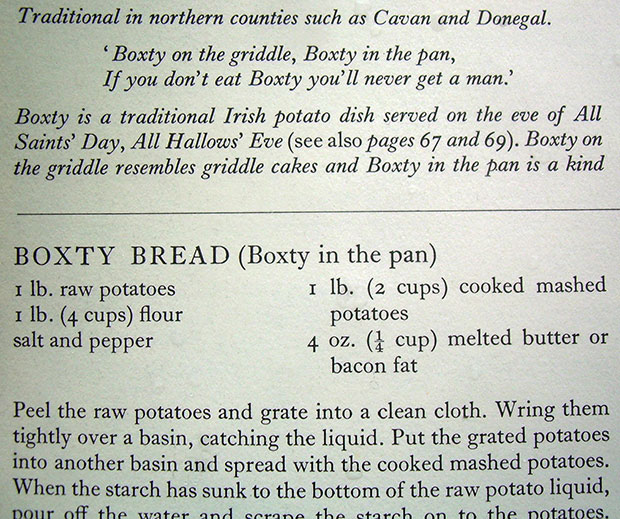

Boxty has been a traditional food in the north-western counties for a very long time. There is an association with Halloween and the late crop of the year. Its similarity with the Swiss pan-fried grated potatoes and with the potato dumplings of the Baltic countries may be coincidental, or not.

Farrelly is glad boxty now has a profile. In 1983, boxty was an enigma. It was known in west Cavan, Leitrim, Longford, parts of Mayo and in north Roscommon but not in east Cavan or Monaghan or the rest of the country. When he tried to sell their boxty, one woman queried him: “Why would I want to buy your boxty, when I make my own?”

But Farrelly and Nan persevered, buying custom-made equipment from a factory in Broughshane in County Antrim, Very gradually, Drummully Boxty was established.

By refining the traditional method and by using good Rooster potatoes from County Meath, Farrelly and his mother created a business that now employs three people, keeping them all at home, away from the ignominy of migration, rooted in their place. Just like the song.

Joe McGee is a successful artisan butcher, a member of the Craft Butchers of Ireland. He cures his own bacon and makes weekly 300 kilos of sausages, selling them to eager customers from a unit in the Letterkenny Shopping Centre, a traditional food oasis in a country bereft of its own traditional produce.

McGettigan's bakery, back along the mall, make some of the best barm brack, tea and whiskey cake anywhere in Europe.

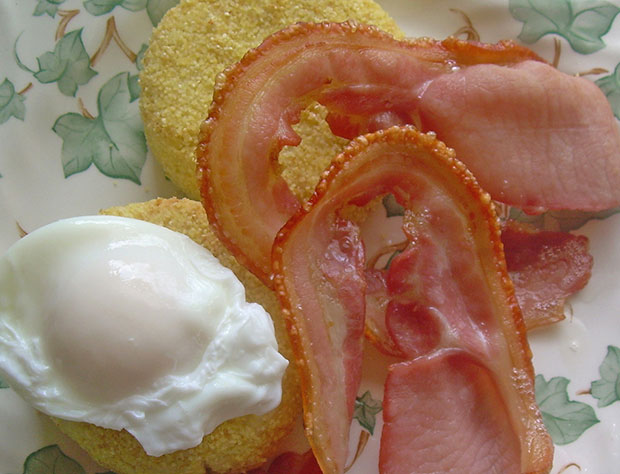

• Healthy breakfast – Eggs are poached, potato cakes are baked and rashers are grilled

The Tesco across from Joe's is the place to go for that delicious mackerel from Dinish, and for natural buttermilk from Mayo, cheeses from the hills and valleys of Cork and Tipperary and large bottles of Irish whiskey.

There is that much-vaunted PGI (product of geographical indication), the EU symbol of quality for traditional food. Each product should fulfill a specific criteria, simply described as place, people and produce.

Historical evidence is crucial but it is the geographical criteria that determines whether a symbol is issued.

The EU's traditional food project of two decades ago was serviced by academics who hid their results from the public domain, not least the Irish project by Teagasc (the Agriculture and Food Development Authority) and hardly seen since.

Unlike countries like Switzerland, where the results were put on an accessible online database, Ireland has only legends and myths about its traditional food, and the ancestral line into the past has been cut by the modern trend for street fast food and supermarket junk food.

Irish food history is divided between the big house and the small cottage, between the city and the townland, and between those with and those without! Very few of our traditional recipes were written down. Those who did the writing came from the big house and wrote their own food history.

• Theodora FitzGibbon's 'A Taste of Ireland' (published in 1968) is now a collector's item

The Allens of Ballymaloe made an effort to collect traditional recipes from their east Cork neighbours but Theodora FitzGibbon's A Taste of Ireland, published in 1968, remains the only genuine traditional recipe book, and it is also a collector's item.

Early Irish food was based on grains – barley, oats, spelt – on forest forage, on game meat, on inshore, lake and river fish, on eggs, on honey and on wild berries and fruit.

Oats, in particular, were used in numerous ways: in soups and stews, in confections like honeycomb, and as the essential ingredient in griddle bread. They were fermented to provide a leaven for bread.

Cockle, crab, eel, haddock, herring, langoustine (Dublin bay prawn), lobster, mackerel, pike, salmon, trout and winkle provided protein for coastal, lake and river communities. Sea vegetables such as carrageen and dulse were used variously.

Meat from birds (duck and goose), small animals (hares and rabbits) and large animals (boar/pig and deer) was common, and defined traditional dishes.

The potato had a profound effect on rural food. Usually cooked whole in their skins, a method that retained minerals and vitamins, the potato was used as a thickener for soups (early chowders, for example), as a bulking agent in stews and as a companion for countless dishes – boxty, champ, colcannon, fadge, farls and pratie among them.

• Joe packages and sells champ – creamed potato with scallions

Mutton, a high table dish, became an essential food in the late 18th century. The consequence was Irish stew, made initially with mutton neck bones, potatoes, onions and salt, then much latter with other root vegetables and herbs.

Breadmaking went through countless adaptations in the early 19th century as new ingredients (bicarbonate of soda, dried fruit, molasses, soft wheat, spices and sugar) led to the beginnings of many of our baked products.

Breakfast became the most important meal of the day and epitomised traditional food, continuing to this day. Depending on the region, breakfast included a combination from bacon rashers, black and white puddings, fried eggs, pork and steak sausages, potatoes in their various guises, wheaten and white soda bread, scones with butter, jams and preserves, milky tea or coffee with hot milk.

Fast breakfast was fadge – bacon, eggs and potato cakes.

The concept of plated meat, vegetables and potatoes, probably started in Dublin. It was certainly a tradition in city restaurants, now the preserve of the food pub. Ham or bacon, cabbage and mashed potatoes remain a favourite. Nowadays the carvery is popular, usually roast stuffed pork, carrots, gravy and mash. In the food pubs sirloin steak, crispy onion and chips are now thought of as traditional.

Yet, despite this rich culinary history, Ireland sits last on the traditional food table of Europe.

The mackerel fishers of Cork, the boxty makers and cheese producers of Cavan and the bacon curers and brack bakers of Donegal are few and far between.

A bit like the land and the sea, where the mackerel used to be.